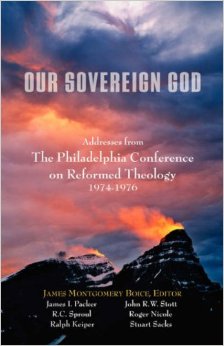

Excerpt from the outstanding book Our Sovereign God ed James M. Boice

Personal names in the Old Testament were designed to communicate something distinctive about the individual or his circumstances. Students of Scripture are well aware of the significance attached to names like Abraham and Jacob, Moreover, the change in Abram's name to Abraham, and Jacob's name to Israel, marked great epochs in the lives of these patriarchs. On occasion an Old Testament name spoke of conditions surrounding a child's birth, as in the name Ichabod (1 Sam. 4:21). On other occasions, the names of children expressed parental hopes for their offspring (Gen. 35:18).

Personal names in the Old Testament were designed to communicate something distinctive about the individual or his circumstances. Students of Scripture are well aware of the significance attached to names like Abraham and Jacob, Moreover, the change in Abram's name to Abraham, and Jacob's name to Israel, marked great epochs in the lives of these patriarchs. On occasion an Old Testament name spoke of conditions surrounding a child's birth, as in the name Ichabod (1 Sam. 4:21). On other occasions, the names of children expressed parental hopes for their offspring (Gen. 35:18).

It is a superior being, in exercise of his prerogatives, that produces names for other beings. Adam named the creatures, defining them with names suiting their nature and actions. Yet the names that humans affix to others convey depth only insofar as God himself inspirationally motivates such procedure. Moreover, if God led the Jews to identify their fellows with deeply significant names, we should well expect that the Creator, in telling us his names, would also convey something of depth concerning his nature.

The names to be considered here are not names which man gives to God but rather names which God ascribes to himself. Certain divine names are predominant in different periods of revelation, yet such circumscribed usages do not, as some assert, throw suspicion upon the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch. They do serve to describe the spiritual significance of a given period. El Shaddai, for example, "the Almighty God," is the most common revelation of God in the patriarchal period. Why? Because the patriarchs desperately needed the assurance that such a powerful name provided. We must keep in mind, however, that the Old Testament does not dwell upon what men thought about God. It centers upon what God, in infinite condescension, made known to men.

A SOVEREIGN GOD

Exodus 20:7 implies that all scriptural names identifying God are to be held in sacred awe. Such a command would be presumptuous were it not uttered by the most supreme being. The diversified pattern of Old Testament divine names confirms the fact of God's absolute supremacy, his sovereignty. We generally refer to the Bible as the Word of God. More appropriately we might refer to it as the "Acts of God." These acts reveal one who directs all things after the counsel of his own will.

Present-day conditions cry out for a vital proclamation of God's mighty and limitless dominion. The prophet Daniel said: "And he changes the times and the seasons; he removes kings, and sets up kings" (Dan. 2:21). Later, in the fourth chapter, he wrote: "... the Most High rules in the kingdom of men, and gives it to whomsoever he will, and sets up over it the basest of men. . . . And all the inhabitants of the earth are reputed as nothing; and he does according to his will in the army of heaven, and among the inhabitants of the earth, and none can stay his hand, or say unto him, What are you doing?" (Dan. 4:17, 35).

The expression, "the sovereignty of God," grew out of ancient oriental societies where the king was truly sovereign. The nucleus of political life was the king, for whose sake the state and citizens existed. He held absolute power over his subjects and all property was under his aegis. He was the supreme authority, the maker and enforcer of every law. Mercy, justice, wrath, and fury were his to display as he found fit. Thus, in Genesis 2:16, as the Lord God places a command upon man, the authority with which he speaks immediately witnesses to his sovereignty. The trees of the Garden are his, and man may partake of them only by permission of the owner. The matter admits no prerogative for man; he is at the disposal of the one who issues the command.

While many of the Semitic peoples used melek ("king") to identify the deity, only the people of Israel were to learn of the reality of God's sovereignty in an indisputable manner, that is, through his supernatural interposition as king of their nation. In Isaiah 33:22 God is beheld as both lawgiver and administrator of the law. While this concept does not commend itself to us from a purely political standpoint, it is of vital necessity in the kingdom of God. An absolute monarchy is the only viable principle for a truly theocratic government. Man's failure to understand the sovereignty of God stems from the creature's self-directed theology, by which he prefers his own subjective impressions to those of God's Word.

It is hardly possible to study the sovereignty of God apart from those attributes defined as omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence. These qualities, in fact, frame essential parts of the picture of the sovereignty of God. It is God's omnipotence that guarantees his sovereignty in the manifestation of might; it is his omniscience that determines the delegation of authority to men; it is his omnipresence that sees to the appropriation of mercy and grace. When man comprehends that God is God, the individual rests on a firm foundation for the experience of God's person. Far from being abstract knowledge for its own sake, a correct conception of God's sovereignty is itself a mode of honoring and glorifying God. As our conception of him is elevated we will be humbled into submission to his will, relying solely upon him for the great work of salvation and the security he can uniquely provide. As we better understand his sovereignty we cannot help but praise and glorify him more realistically.

No man motivated God to reveal his name. Seven out of every twelve references to the name of God declare it as qedosh ("holy"). In other words, he is unapproachable. He cannot be encountered by sinful man apart from some extraordinary gracious provision emanating from himself. Therefore, that we should know his name reveals God's volitional self-disclosure to a chosen people. Such revelation is the result of the sovereign's purpose to make himself known.

THE STRONG ONE

In antiquity an extensively used term for deity was the word El and its related forms: Elohim, Elim, and Eloah. El seems to be related to the verbal root ul ("to be strong"). An alternate etymology yields the idea of commanding leadership. In fact, all variants in derivation support this sense of power or might in its most dynamic form. Isaiah sarcastically named the idols elilim, a diminutive of El, to show the impotence of the heathen deities in contrast to the true God of Israel. Elilim could be translated "good-for-nothing-ones."

Elohim is a masculine plural noun which we may call "the plural of greatness." It is an intensification of the singular El, expressing the superhuman power of the Almighty. "In the beginning Elohim created the heaven and the earth" (Gen. 1:1). Elohim signifies the "put-er forth" of power. He is the Being to whom all power belongs.

When El is combined with Elyon ("highest") we arrive at a conception of God which elevates him above all else in the universe. Elyon is rooted in elah, which means "to go up" or "to be elevated," thus declaring the extreme exaltation of God. It is in the name of El Elyon, the Most High God, that Melchizedek blesses Abraham (Gen. 14:19). Notwithstanding the election of Abraham, a select few outside the patriarchal family were sovereignly introduced to the God of their salvation. Melchizedek, a man with pre-Abrahamic knowledge of God, was one of these recipients of God's grace. A profound principle is operative here. There is a chosen people called through election which, although particularistic, extends beyond ethnic groups to encompass all whom God has sovereignly made the objects of his grace. While El and Elohim are found in Canaanite texts relating to deity, the one upon whom Melchizedek calls is the sole possessor of heaven and earth. Similarly, Abraham thinks of God as the only true creator-sustainer of the universe (Gen. 14:22).

Further affirmation of God's sovereign administration is found in the Aramaic texts of Daniel where 'lllaya' and 'Elyonin (synonyms for Elyon) bear witness to the absolute control of God over all creation (Dan. 4:17; 7:18, 22, 25, 27). In the seventh chapter we see how God volitionally identifies himself with a group called "saints," his "called-out ones." In concert with this, Jacob refers to God as El-Elohe Israel ("God is the God of Israel"), thereby attesting to the special revelation of God leading to the salvation of his elect. The adoption of Israel was not an act of choice upon the part of Israel but rather the product of a sovereign administration of grace subsumed under the word "covenant," of which Adam was the original partaker.

Why should God have chosen a select minority as opposed to the countless cultures extant both then and now? This irresolvable mystery must be considered within the context of God's sovereignty. Job affirmed that every soul is in his hand, even "the breath of all mankind" (Job 12:10). It is God that "leads counselors away spoiled, and makes the judges fools" (Job 12:17). If God is the Deus absconditus to some, it is because he has chosen to remain incomprehensible to them.

STABILITY

El is intensified when combined with Shaddai to represent God's self-disclosure during his people's earliest history. Commonly rendered "the Almighty God," El Shaddai communicates the majesty, might, and stability of God.

Rabbinical tradition says the name's two particles speak of complete sufficiency. Shaddai is related to the verb shadad, which speaks of unlimited power (Isa. 13:6; Joel 1:15). The word is also related to the Aramaic for mountain, shadu. Thus, Ezekiel fell awestruck to the ground before the presence of Shaddai (Ezek. 1:24, 28). This name provided Israel with transitional knowledge leading from the use of Elohim to the extraordinary personal revelation of God as Yahweh. While Elohim revealed God primarily in terms of his rule over creation in general, El Shaddai made men aware of the way in which God subdued and molded all these forces in the performance of his will. El Shaddai also speaks of God as provider for his children. Thus, the ancient Jews referred to him as Makohm ("place"), for in him all things subsisted and were sustained. Abraham knew him as the source of life's necessities (Gen. 22:13), for he who promised was faithful. God's immutable sovereignty backed every promise. In the context of Genesis 17, God's self-presentation as El Shaddai served as a pledge that, despite the barrenness of Sarah's womb and the virtual impotence of Abraham, God could and would provide the innumerable progeny he had promised. "Overpowerer" would serve excellently as a synonym for this name.

God is called Shaddai more frequently in Job than in any other Old Testament book. Such usage is deeply meaningful for, in the midst of perplexity and anguish, cognition of the sovereignty of God becomes all the more necessary. Because he is gracious his sufficiency is made abundantly real in our extensive insufficiencies. There is bittersweet release for the one who, in the throes of conflict, can say with Job, "The arrows of Shaddai are within me" (Job 6:4). Although Job's problem with suffering is never fully resolved, a vision of his Kinsman-Redeemer supplies his deepest need. The key to Job's consolation is simple trust in God, in which lies the essential redemptive theme of the book bearing his name. The fact that God has promised never to leave or forsake his children engenders trust in his sovereignty.

The second syllable in Shaddai, ai, is commonly a possessive suffix in the Hebrew. God's limitless ownership is a key factor in our understanding of his sovereignty.

DIVINE OWNERSHIP

Ownership is also an integral factor in the use of the word Adonai ("Lord"), another prominent word in the patriarchal period. In Genesis 24:12, 14, Abraham is addressed as such to denote his role as a master of servants. Adonai may actually be translated "my Lord" as it expresses the user's submission to his master. The derivation of Adonai conveys the idea of judging and ruling, thereby pointing to God as the almighty monarch whose reign governs the inanimate as well as the animate. At the very least it signifies God's complete ownership of each member of the human family.

THE ONLY TRUE NAME

Yahweh, occurring some six thousand times in the Old Testament, is, strictly speaking, the only true name of God. Its spiritual usage is not found in the history of Semitic tribes contemporaneous with ancient Israel. While other Old Testament designations describe his dealings and attributes, Yahweh is what Genesis calls the name of God. The name occurs more than twice as much as its nearest competitor, Elohim.

Even before the time of Christ, Jews feared to pronounce this name, substituting Adonai whenever the four Hebrew letters representing Yahweh (Y-H-W-H, called the Tetragrammaton) appeared in Scripture. By so doing they hoped to avoid the penalty they found in their lamentable misreading of Leviticus 24:16-"He that blasphemeth the name of [Yahweh], he shall surely be put to death." Students of the apocryphal literature notice the conspicuous absence of that divine name there. Among orthodox Jews there has always been the belief that the Messiah would have the right and ability to restore the lost pronunciation. "Jehovah" is certainly inaccurate.

It is with the call of Moses that this name takes on special significance. It is explained in Exodus 3:14 as "I am that I am" or, better, "I will be what I will be." Intrinsically the name displays God's continual presence and the demonstration of his power to redeem his people. It points to his constancy as the covenant-keeping Redeemer. Hence we read, "I am [Yahweh], I change not" (Mal. 3:6). By using the name with Moses, God was making known the fact that he would bless Moses and his people as he had blessed the patriarchs before him. In all this Yahweh shows self-determination; he is not influenced by outside forces. Shem's inspired note of praise in Genesis 9:26 affirms this fact. In effect the patriarch said, "Blessed be Yahweh, because he is willing to be the God of Shem."

The redemptive value of the name became experientially revealed to the enslaved Israelites in Egypt in a way previously unknown (Exod. 6:3). Moreover, that miraculous deliverance showed God's sovereign rulership over all the forces of nature, including the false Egyptian gods. The positive determinism of Yahweh's revelation is forcefully stated when he says, "I will take you to me for a people, and I will be to you a God: and you shall know that I am [Yahweh], your God" (Exod. 6:7). What could more fittingly portray God's sovereignty than that trio of expressions: "I will take," "I will be," and "you shall know"? The serpent of Genesis knows nothing of Yahweh's sovereign redeeming strength and refers to God only with the general word Elohim.

Yahweh's words, "I will be gracious to whom I will be gracious" (Exod. 33:19), are intimately related to the definition provided by Exodus 3:14. These words will always be a source of deepest joy to God's elect, for he cannot be thwarted in carrying them out.

The psalmist is prolific in regard to this theme. In Psalm 23, in a type of biblical shorthand, he records the sevenfold operation of God's redemptive power in his life: Yahweh makes, leads, restores, guides, is with him, prepares a table, anoints. "To know him" in the sense of Exodus 6:7 implies a practical experimental penetration into his sovereignty. Genesis 15:6 says literally that Abraham "developed trust in Yahweh." But what motivated that trust? Was it not the sure word of the sovereign God in concert with the direct revelation of Yahweh to Abraham? It is the same today as it was in the time of Elijah when the word of Yahweh assured the salvation of seven thousand souls (1 Kings 19:18). Your salvation and mine is determined by the one who exercises the right to make one vessel unto honor and another unto dishonor.

The title Adonai Yahweh occurs 293 times in the Old Testament, 217 of them in the Book of Ezekiel, where the prevalent theme is the sovereignty of God. Ezekiel concludes logically that men should glorify God. It was in the midst of spiritual decline and lethargy that Ezekiel proclaimed that message. His exalted vision rested on the formula co-amar Adonai Yahweh ("Thus saith the Lord Yahweh" [Ezek. 2:4]). We of this generation must, as Ezekiel, see God's commands as pre-emptory and irresistible. "As Yahweh spoke, so he also did" is the recurrent witness of Scripture and history (Gen. 21:1; Ezek. 17:24).

To the serpent God said, "I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and her seed" (Gen. 3:15). Here was no act requiring or even soliciting cooperative assistance. God did not say to Adam and Eve, "Be at enmity with the serpent," but "I will put enmity.. .." The entire revelation attests to the manner in which that enmity was sovereignly established. That God should manifest himself as man's Savior reveals an entirely autonomous act, for man has nothing within him entitling him to such favor from God. The imposition of the covenant of grace upon man stems from a purely one-sided movement of which God is the sole initiator.

LORD OF HOSTS

Yahweh is often linked with Tzebaoth, which shows God as commander-omnipotent in the universe. In the orient the might of a king is measured by the splendor of his retinue. Yahweh's hosts include all created agencies and beings. Isaiah records God's com¬plete mastery of creation, beginning at Isaiah 24:23, where even the glory of the sun is but an adumbration of his glory. The absolutely exhaustive control of Yahweh Tzebaoth motivated the translators of the Septuagint to render the name ho Pantokrator ("the all-ruler"). In 1 Samuel 1:11 Hannah's prayer to Yahweh Tzebaoth appropriately reflects humble submissiveness in cognition of God's sovereignty. Indeed, apart from such cognition all prayer is reduced to little more than wishful thinking. Yahweh Tzebaoth occurs most frequently following the Babylonian exile, some eighty citations given in Jeremiah alone. The post-exilic usage evinces the warlike quality of the name and reaffirms the invincibility of the Sovereign who liberates Israel. In conjunction with this militant picture we observe that the Messiah himself is prepared for combat, as seen in Isaiah 11:5. In the midst of brilliant visions of the end time Isaiah sees Christ as a warrior.

Consonant with this vision are his pre-incarnate manifestations as the Angel of Yahweh, also revealed as "the Angel of his Presence" (Gen. 16:7ff.; 22:15, 16; Exod. 3:2-4; Isa. 63:9). Once again, it is God who sovereignly takes the initiative, invading man's space-time continuum that a fallen race may have access to life, and that more abundantly. The paradox of the Angel, who is both identified with the Lord (Gen. 22:11, 12) and yet distinguishable from him (Gen. 22:15, 16), remains enigmatic until the God-Man himself appears in the fullness of time.

It is the omnipresence of Yahweh Shammah ("the Lord is there") that brings God's promise to fruition. The ancient hieroglyphic for God was an eye upon a sceptre, to illustrate that he sees and controls all things. Many err in thinking that because God is designated as a Spirit (Ruach) he is without substance; for, rather than connoting immaterialness, "Spirit" actually describes the nature of the power residing in God. While God's presence may in one sense be localized, there is, nevertheless, no place in the universe where his presence is not manifested or his power lacking.

GOD WITH US

We cannot think of the localization of that power without thinking of the Messiah, in whom God's sovereignty appears so gloriously. Despite the infrequency of Mashiach ("anointed") as an actual name of God, the title nonetheless points to the ideal sovereign kingship in an eschatological ruler. This potentate is the Son of God.

While the Old Testament has no single word to express the omnipotence of God, the series of descriptions pertaining to Immanuel ("God with us," Isa. 7:14) in Isaiah 9:6 certainly gives that concept full breadth. Isaiah calls him Pele Yoetz ("Wonderful Counselor"), El Gibbor ("Mighty God"), Abhi Ad ("Everlasting Father"), and Sar Shalom ("Prince of Peace"). The crying need of man is to know this one who, by his very nature, is a "wonder." His ministry is unique in its comprehensiveness: Prophet (Deut. 18:15ff.), Priest (Ps. 110:4), King (Isa. 11:Iff.). His omniscience as Counselor (Yoetz) makes him the source of all truth; in fact, he is its actual embodiment. His underived existence as our paternal Christ brings inexhaustible fullness to our souls. Plenitude of life stems from the peace that passes all understanding, peace that he alone can give. Jesus spoke the words ego eimi ("I am") in John 8:58, thereby showing his inalienable right to the sacred name. He wields the same sword of authority as does the Father. To proclaim the sovereignty of Yahweh is also to proclaim him who said, "All authority is given unto me in heaven and in earth" (Matt. 28:18).

Would that all men knew Jesus as he is: Yahweh Tzidkenu, the sovereign provider of our justification (Jer. 23:6). Would that all might echo the words of the psalmist, who said, "Oh, come, let us worship and bow down; let us kneel before the Lord our maker" (Ps. 95:6).

Chapter of the outstanding book Our Sovereign God ed James M. Boice