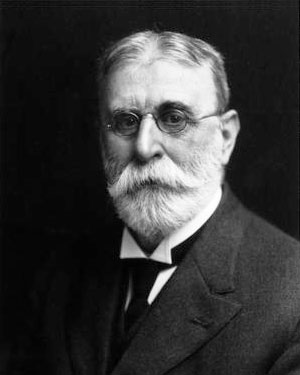

Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield

WHAT may very properly be called the Chalcedonian "settlement" has remained until today the authoritative statement of the elements of the doctrine of the Person of Christ. It has well deserved to do so. For this "settlement" does justice at once to the data of Scripture, to the implicates of an Incarnation, to the needs of Redemption, to the demands of the religious emotions, and to the logic of a tenable doctrine of our Lord's Person. But this "settlement" is a mere statement of the essential facts, and therefore does nothing to mitigate the difficulty of the conception which it embodies. The difficulty of conceiving two distinct natures united in a single person remains; and this difficulty has produced in every age a tendency more or less widespread to fall away from the doctrine, or to explain it away, or decisively to reject it. Weak during the Middle Ages, this tendency acquired force in the great intellectual upheaval which accompanied the Reformation; and then gave birth, amid many other interesting phenomena, to the radical reaction against the doctrine of the Two Natures which we know as Socinianism. The shallow naturalism of the Enlightenment came in the next age to the reinforcement of the movement thus inaugurated, and under the impulses thus set at work a widespread revolt has sprung up in the modern church against the doctrine of the Two Natures.

WHAT may very properly be called the Chalcedonian "settlement" has remained until today the authoritative statement of the elements of the doctrine of the Person of Christ. It has well deserved to do so. For this "settlement" does justice at once to the data of Scripture, to the implicates of an Incarnation, to the needs of Redemption, to the demands of the religious emotions, and to the logic of a tenable doctrine of our Lord's Person. But this "settlement" is a mere statement of the essential facts, and therefore does nothing to mitigate the difficulty of the conception which it embodies. The difficulty of conceiving two distinct natures united in a single person remains; and this difficulty has produced in every age a tendency more or less widespread to fall away from the doctrine, or to explain it away, or decisively to reject it. Weak during the Middle Ages, this tendency acquired force in the great intellectual upheaval which accompanied the Reformation; and then gave birth, amid many other interesting phenomena, to the radical reaction against the doctrine of the Two Natures which we know as Socinianism. The shallow naturalism of the Enlightenment came in the next age to the reinforcement of the movement thus inaugurated, and under the impulses thus set at work a widespread revolt has sprung up in the modern church against the doctrine of the Two Natures.

Germany is today the præceptor mundi. And how things stand in the academical circle of Germany Professor Friedrich Loofs informs us in his recent Oberlin lectures. "The whole German Protestant theology of the present time," he tells us, has, "to a certain extent," turned away from the conception of the Two Natures. "In the preceding generation," it seems, "there was still a learned theologian in Germany who thought it correct and possible to reproduce the old orthodox formulas in our time without the slightest modification, viz.: Friedrich Adolph Philippi, of Rostock (1882)." "At present," however, Loofs proceeds, "I do not know of a single professor of evangelical theology in Germany of whom this might be said. All learned Protestant theologians in Germany, even if they do not do so with the same emphasis, really admit unanimously that the orthodox Christology does not do sufficient justice to the truly human life of Jesus, and that the orthodox doctrine of the two natures in Christ cannot be retained in the traditional form. All our systematic theologians, so far at least as they see more in Jesus than the first subject of Christian faith, are seeking new paths in their Christology." No doubt matters have not yet gone so far in lands of English speech; but the drift here, too, is obviously in the same direction, and even among us an immense confusion has come to reign with regard to this fundamental doctrine of the Christian religion.

The alternative of two natures is, of course, one nature: and this one nature must be conceived, naturally, either as Divine or as human. The tendency to conceive of Christ as wholly Divine—so far as it has asserted itself at all—has been rather a religious than a theological tendency, if we may avail ourselves here of this overworked and misleading terminology. It has existed rather as a state of heart, and as a devotional attitude, than as a reasoned doctrine. Nothing has been more characteristic of Christians from the beginning than that they have been "worshippers of Christ." To the writers of the New Testament, the recognition of Jesus as Lord was the mark of a Christian; and all their religious emotions turned to Him. It has been made the reproach of the Evangelists that they—following their sources—were all worshippers of Jesus: and it is precisely on that ground that modern naturalistic criticism warns us that we are not to trust their representations as to His supernatural life on earth. To the heathen observers of the early Christians, their most distinguishing characteristic, which differentiated them from all others, was that they sang praises to Christ as God. A shrewd modern controversialist has even found it possible to contend that the only God the Christians have is Christ. "Christianity," says he, "is pre-eminently the worship of Christ. Far away in the background of existence there may be a power, answering to Indian Brahma or Greek Kronos and conceived as God the Father. But the working, ever-living, ever-active Deity is Christ. He is the creator and preserver of the world, the ruler, redeemer, and judge of men. He and no other is worshipped as God, hymned, prayed to, invoked. To Him have been transferred the attributes of Jehovah. He and no other is the Christian God." If there is some exaggeration here, it is not to be found on the positive side; and G. K. Chesterton is not overstating the matter when he speaks of Christ incidentally as "the chief deity of a civilisation."

This worship of Christ has had, of course, theological results of great importance, some of them even portentous—if, for example, we can with many historians look upon adoration of saints, and especially of the Virgin Mary, as, in part at least, an attempt of the human spirit to supply, outside of the Christ thought of as purely Divine, the human element in the mediatorially conceived Divine relation. But only now and again has it worked back and sought a theological basis for itself by the formal divinitising of the whole Christ. We think here naturally of the Apollinarians, and the Monophysites; but more particularly of confessional Lutheranism, which by its theory of the communicatio idiomatum managed to preserve indeed to theology a human nature for Christ, but at the same time to present a purely Divine Christ to our religious emotions. But we shall have to go back to the Gnostic Docetism of the first Christian centuries for any influential effort speculatively to construe Christ as a wholly Divine Being. If men have here and there forgotten the human Christ in their reverence for the Divine Christ, they have shown no great inclination to explain Christ to thought in terms of the purely Divine.

Revolt from the doctrine of the Two Natures means, therefore, nothing more or less than the explanation of Christ in terms of mere humanity. When we are told by Loofs that the whole of learned Germany has rejected the doctrine of the Two Natures, that is equivalent accordingly to being told that the whole of learned Germany has rejected the doctrine of the Deity of Christ, and construes Him to its thought as a purely human being. It may continue to reverence Him; men here and there may even continue to worship Him. As many of the older Unitarians found it possible still to offer worship to Christ, and incorporated in their official hymn-books hymns of praise to Him as God—such as Bonar's "How shall Death's Triumph end?" in which Christ is celebrated as "The First and Last, who was and is," or Ray Palmer's "My Faith looks up to Thee," in which he is addressed as "Saviour Divine"—so many of our new German Humanitarians still worship Christ. Karl Thieme, for example, who righteously rebukes his fellows for continuing to use such phraseology as "the Godhead," "the Deity," "the Divinity" of Christ, when they know very well that Jesus is not God but only man, yet strenuously argues that He is worthy of our worship, because of what he calls His "representative unity with God." When asked how his worship of Jesus differs in principle from the gross hagiolatry of the Church of Rome, Thieme naïvely and most significantly replies, Why, in this most important respect, that he worships only one such holy one, the Romanists many! The adoring attitude preserved by men of this class towards Jesus—whom they nevertheless declare to be mere man—has called out not unnaturally in wide circles a deep disgust. They are not unjustly reproached with idolatry, are contemptuously dubbed "Jesusites"—worshippers of the man Jesus; and occasion has even been taken from their corrupt Jesus-cult to inaugurate a movement in revolt from Christianity as a whole, wrongfully identified with them, in the interests of a pure and non-idolatrous service of God. Men like Wilhelm von Schnehen and Arthur Drews are thus able to come forward with the plea that in their philosophical cult alone can be found true worship, and do not hesitate to declare that the greatest obstacle to pure religion in the world to-day is precisely this idolatrous adoration of Jesus, interpreted as merely a human being. We can only record it to their honour, therefore, when the majority of those who have given up the Deity of our Lord refuse to worship Him, and, while according to Him their admiration and respect, reserve their religious veneration for God alone.

The present great extension of purely humanitarian conceptions of the person of Christ has, of course, not been attained without a gradual development, in the progress of which there has been enunciated a variety of compromising views seeking to mediate between the doctrine of the Two Natures and the growing Humanitarianism. The most interesting of these is that wonderful construction which has been known under the name of Kenotism, from its vain attempt to intrench itself in the declaration of Paul (Phil. ii. 8) that Jesus, being by nature in the form of God, emptied Himself—as our Revised Version unfortunately mistranslates the Greek verb from which the term, Kenosis, is derived—and so became man. The idea is that the Son of God, in becoming man, abandoned His deity, extinguished it, so to speak, by immersing it in the stream of human life. This curious view bears somewhat the same relation to the tendency to think of Christ in terms of pure humanity that the Lutheran Christology bears to the opposite tendency to think of Him in terms of pure deity. As that was an attempt to secure a purely Divine Christ while not theoretically denying His human nature, so this was an attempt to secure a purely human. Christ without theoretically denying His Divine nature. In effect it gives us a Christ of one nature and that nature purely human, though it theoretically explains this human nature as really just shrunken deity. Therefore Albrecht Ritschl called it verschämter Socinianismus—Socinianism indeed, but a Socinianism differing from the bold Socinianism to which we are accustomed by shyly hanging back and trying to hide itself behind sheltering skirts.

Kenotism differs from Socinianism fundamentally, however, in that Socinianism took away from us only our Divine Christ, while Kenotism takes away also our very God. For what kind of God is this that is God and not God alternately as He chooses, and lays off and on at will those specific qualities which make God the kind of being we call "God," as a king might put off and on his crown, or as a leopard might wish to change his spots but cannot, or an Ethiopian his skin? Of course, this is all—as Albrecht Ritschl again aptly described it, and as Loofs repeats from his lips—"pure mythology"; and the only wonder is that it enjoyed considerable vogue for a while, and, indeed, has not yet wholly passed out of sight on the outskirts of theological civilization. Loofs seems to raise his eyebrows a little as he remarks that, as it has gradually died out in Germany, it has seemed to find supporters in England: "in Sweden, too," he adds, with meticulous conscientiousness, "it was confidently defended as late as 1903 by Oskar Bensow." The English writers to whom he thus refers are men of brilliant parts—such as D. W. Forrest, W. L. Walker, P. T. Forsyth, and latest of all H. R. Mackintosh. But even writers of brilliant parts will not be able to fan the dead embers of this burned-out speculation into life again. The humanitarian theorizers are in search of a true man in Jesus, not a shrivelled God; and no Christian heart will be satisfied with a Christ in whom (we quote Ritschl again) there was no Godhead at all while He was on earth, and in whom (we may add) there may be no manhood at all now that He has gone to heaven. It really ought to be clear by now that there cannot be a half-way house erected between the doctrines that Christ is both God and man and that Christ is merely man. Between these two positions there is an irreducible "either or," and many may feel inclined to adopt Biedermann's caustic criticism of the Kenotic theories, that only one who has himself suffered a kenosis of his understanding can possibly accord them welcome.

On the sinking of the Kenotic sun beneath the horizon, there has been left, however, a certain afterglow hanging behind it. A disposition is discoverable in certain quarters to speak in Kenotic language while recoiling from the Kenotic name; to claim as a Christian heritage the essential features of the Kenotic Christology while declining to lay behind them the precise Kenotic explanation. An isolated early instance of this procedure was supplied by Thomas Adamson, who draws a portrait of Jesus in his "Studies of the Mind in Christ" (1898) which seems to require the assumption of kenosis to justify it, but who vigorously repudiates the attribution of that assumption to him. Much more notable instances are found in such writers as Johannes Kunze of Vienna (now of Greifswald) and Erich Schäder of Kiel, whose formula for the incarnation is that in Jesus Christ the Godhead is "presented in the form of a human life." According to Kunze the Godhead appears in Jesus always as humanly mediated: the two, Godhead and manhood, can never be contemplated apart; all that is human is Divine, and all that is Divine is human. The omnipotence which belongs to His deity appearing in Christ only as humanly mediated, for example, is conditioned on His prayer; Jesus could accomplish all things by the power of prevalent prayer! So also with all the Divine attributes; the result being that we have in Jesus phenomenally nothing but a man, but a man who, we are told, is nevertheless to be thought of as the Eternal God.

Similarly, according to Schäder, God in becoming flesh has not at all ceased to be what He was; He has only become it "in another way." In the place of the doctrine of the Two Natures, Schäder places the idea of what he calls "the Being of God in Jesus"—das Sein Gottes in Jesus—a phrase which becomes something like a watchword with him. "We have here," he says, "a man before us to whom there is lacking not the least thing that is human, a man who is man in everything, be it what it may"; and yet who is just God become flesh, "having ceased to be nothing which He eternally is," but "having only become it in another manner." By what a narrow line this doctrine of "God in human form" is separated from express Kenotism may be observed from the difficulties in which Schäder finds himself when he comes to speak of the act by which the mighty transformation, which he postulates in the Son of God, takes place. Here his language is not only distinctly Kenotic, but extremely Kenotic, assimilating him in his subordinationism and transmutationism to what Loofs does not scruple to speak of as the "reckless" teaching of Gess. "Now, God our Father," he writes, "lets it, lets this Son proceed from Himself as man, and thus enter into history. This is an almighty act of His love, of His reconciling will": "what is in question here is an almighty transformation of the mode of being of the Logos by God." When we are thus told that, "by God's almighty act, God's eternal Son becomes a weak, developing child," we are not so much reassured as puzzled that we are told in the same breath that thus "He does not cease to be what He was, He only becomes the same thing in another way"; nor are we much helped by having it explained to us that even in His pre-existent state the Son of God, because He was Son, was dependent on God, subordinate to Him, and wrought only God's will—so that even in His pre-existent state He used prayer to God, preserved humility in the Divine presence, and lived in obedience to God. It is only borne strongly in upon us that it is an exceedingly difficult task at one and the same time to evaporate and to preserve the true Deity of Christ.

The fundamental formulas with which Kunze and Schäder operate—that the incarnation consists in "the Being of God in Christ," that "God is in Christ in human form"—reappear in perhaps even more purity in the writings of the late R. C. Moberly. "Christ," he says, "is, then, not so much God and man, as God in, and through, and as man." "God, as man, is always, in all things, God as man"; "if it is all Divine, it is all human too." So also W. P. Du Bose wishes us not to forget that "God is most God at the moment when He is most love," and not to fail to recognise God "in the highest act of His highest attribute," confusing external pomp with internal nobility—all of which has the appearance at least of being only a way of laying claim to the inheritance of the Kenotists, while avoiding the scandal of the name. Reviewing Du Bose, Professor Sanday falls in with the notions he here expresses, and pronounces it likely that the moderns in their insistence on the single personality of our Lord, which is both Divine and human—and, apparently, Divine only because it is perfectly human,—have made an improvement on the old Two Nature doctrine of the Creeds. We may perceive from this how completely the movement is but a phase of the zealous propaganda for a one-natured Christ, and but propounds a new method of submerging God in man. This method is to proclaim the paradox that God is most God when He ceases to be God—when He becomes man. For this condescension marks the manifestation at its height of the highest of all the activities of God—Love.

But we may perceive here, too, what may also legitimately interest us, a stage in the drifting of Sanday's Christological views towards the apparently humanitarian position at which they seem ultimately to arrive. In earlier writings Sanday had taught with clarity the essentials of the Trinitarian Christology, and had pronounced himself unfavourable to the Kenotic speculations. In this review of Du Bose he falls in, however, with Kenotic modes of expression; and soon afterwards he is found confessing himself in some sense a Kenotist—while, nevertheless, in the act of propounding what seems really to be a merely humanitarian Christology. For Sanday's final suggestion is to the effect that we should think of Christ as the man into whose subconscious being—which is to be conceived as open at the bottom and through that opening in contact with the ocean of Deity which lies beyond—the waves of this ocean of Deity wash with more frequency, fullness, and force than in the case of other men, and so with more frequency, fullness, and force make themselves felt in the upper stratum of His being, His conscious self, also than in the case of other men. At the basis of this suggestion there lies a mystical doctrine of human nature, which makes the subliminal being of every man the dwelling-place of God. If we only go down deep enough into man's being, we shall find God; and if the tides of the Infinite only wash in high enough, they will emerge into consciousness. Man differs from man, no doubt, in the richness and fullness with which the Divine that underlies his being surges up in him and enters his consciousness; and Jesus differs from other men in being in this incomparably above other men. There is Deity in Him as well as humanity; but not Deity alongside of humanity, but Deity underlying and sustaining His humanity—as Deity underlies and sustains all humanity. The mistake of the orthodox Christology has been to draw the line which divides the Deity and the humanity vertically: let us draw it rather horizontally, "between the upper human medium, which is the proper and natural field of all active expression, and those lower depths which are no less the proper and natural home of whatever is Divine." Thus we shall have a Christ whose life, though, "so far as it was visible, it was a strictly human life," yet "was, in its deepest roots, directly continuous with the life of God Himself." That the same may be said in his measure of every man Sanday expressly affirms, and he as expressly identifies this Divine element which is to be found at the roots of the being of both Christ and all other men with what the Scriptures call "the indwelling of the Holy Spirit." Christ thus becomes just the man in whom the Holy Spirit dwells in greater abundance than in other men. He is not God and man; He is not even God in man; He is man with God dwelling in Him—as, though less completely, God dwells in all men. We have reached here a Christology which substitutes for the incarnation a notion which librates between the two conceptions of the general Divine immanence and the special indwelling of the Holy Spirit. According as the one or the other of these conceptions is given precedence will it find its affinities, therefore, with one or another widely spread form of the humanitarian theorizing now so popular. For there are many about us who, declaring Jesus to be no more than man, wish to explain the Divine that is allowed also to be found in Him on the basis of the Divine immanence; and there are equally many among us who wish to explain it on the basis of the Divine indwelling or inspiration.

Those who occupy the former of these standpoints are prone to speak of Jesus as "a human organism filled with the Divine thought." This conception may be presented in a very crass form, or it may be clothed in very beautiful language and made the vehicle of very fervent expressions of reverence for Christ. "I see," explains James Drummond, "in the beauty of a rose a Divine thought, which is no other than God Himself coming unto manifestation through the rose, so far as the limitations of a rose will permit; but I do not believe that the rose is God, possessed of omniscience, omnipotence, and so forth. . . . So, there are those who have, through the medium of the New Testament and the traditional life of the purest Christendom, looked into the face of Jesus, and seen there an ideal, a glory which they have felt to be the glory of God, a thought of Divine Sonship which has changed their whole conception of human nature, and the whole aim of their life. . . ." Such a conception, we are told by its advocates, is far superior to the "masked God" of current orthodoxy; it "exalts Christ above all men, and gives Him a place at the right hand of God." He was, no doubt, only a man—a human organism—but He was a man whose "attitude of will was such that God could act upon Him as upon no other in the history of humanity." "From the dawn of consciousness the human Christ assumed such an ethical uprightness before God that God could pour Himself out on Christ in altogether exceptional activities." In Him "for the first and only time the Almighty was granted His opportunity with a human soul," and, "as the Master kept Himself in unique ethical surrender to God, God acted upon Him in such a manner as to make the metaphysical relationship also unique. The ethical uniqueness implies and renders inevitable its corresponding metaphysical uniqueness of relation to God." For, we are told, "it is possible for God so to fill a responsive heart with His own spirit that every word of that soul becomes a word of God, that every deed becomes a deed of God, that every feeling reveals the loving heart of God willing to suffer with His children. In short, the life becomes such a life as God Himself would live were it possible for Him to be reduced to human circumstances. God could not suggest any improvement. He would find this soul such an open channel that He could at last pour Himself out to the utmost drop. There would be such complete mutual sympathy that the sorrows of God would become the sorrows of this soul, and the sorrows of this soul the sorrows of God. If in a moment of distress at the onslaught of sin the soul should cry out, 'Why hast Thou forsaken me?' the distress would be as real to God as to the soul, for every sorrow of either God or this soul would cut both ways. The soul would become God's masterpiece. God would throw Himself into its development with such flood that the metaphysical relationship would be beyond anything known to humanity, and beyond anything attainable by humanity. As the supreme work of the Father, and as the supreme response to the ethical cravings of the Father, such a creation could be called in the highest sense the Son of God."

Perhaps we may say that the exaltation of the man Jesus could go little further than this. And we can scarcely fail to observe that we have before us here a movement of thought running on precisely opposite lines from that of the Kenotic theories. In them we were bidden to observe how God could become man; in this we are asked in effect whether it may not be possible to believe that in Jesus Christ man became God. We are naturally reminded at this point that consentaneously with the rise of the Kenotic theories in the middle of the last century there was born also a contradictory theory—that of Isaac A. Dorner—which, with a much more profound meaning, proposed to our thought a solution of the problems of the incarnation which formally reminds us of that just described. Dorner, beginning with the human Jesus, asked us to watch Him become gradually God by a progressive communication to Him of the Divine Being, so that, though at the start He was but man, in the end He should become in the truest and most ontological sense the God-man. The difficulties of such a conception are, of course, insuperable; it would compel us to think of the Godhead as capable of abscission and division, so that it could be imparted piecemeal to a human subject, or of manhood as capable by successive creative acts of being itself transmuted into Godhead. But it was inevitable that this theory, too, should leave some echoes of itself in the confused discord of modern thought.

We hear these echoes in the high christological construction of Martin Kähler. We hear them also in the lower theories of Reinhold Seeberg. According to Seeberg, Jesus Christ is just a man whom the willing God has created as His organ and through whom the personal will of God has so worked that He has become fully one with this personal will of God. "The will of God," he says, "chose the man Jesus for His organ, and formed Him into the clear and distinct expression of His Being. He emphasizes the personal character of the Divine will in Jesus, but he allows no second hypostasis in the Godhead as its Trinitarian background. In his view we can admit the eternal existence of only one thinking and willing Divine personality, though in that one personality there co-existed a threefold tendency of will. That particular tendency of the Divine will-energy which aims at the realization of a church, manifests itself in the man Jesus, and so fully takes possession of Him that in Him it becomes for the first time personal and makes Him really the Son of God. Before God thus created Jesus into His organ there was no second ego standing over against the Father; there pre-existed in the eternal God only the eternal tendency of will to create a church. "What is peculiarly Divine in Christ" is therefore only "the peculiar will-content which we can distinguish from other will-contents, the tendency of the Divine will to the historical realization of salvation." Seeberg thinks that thus he does justice to the Godhead of Christ. He looks upon Him as the Redemptive Will of God forming as organ for itself a human subject and coming to complete personality in it. "Jesus," he says, "in the peculiar contents of His soul is God." "Herrschaft," authority, therefore belongs to Him; but also "Demut," humility; but especially "Herrschaft," for is He not the personal Son of God, the only personal Son of God that ever was or ever will be? "That ever will be," we say: for the question arises, what has become of this personal Son of God now that His life on earth is over and He has ascended where He was before? As before the "Incarnation" the particular Divine will of salvation was not a Divine personality over against the Father, but acquired personality only as it flowed into the human person, Jesus Christ, and formed Him to its organ—has it, now that this man Jesus has passed away from earth, lost again its personality and sunk again into merely the tendency of the Divine will making for salvation? It is Karl Thieme who asks this question. For ourselves, we may be content with observing that in Seeberg's construction it is not God, but only the Divine will of salvation, that becomes incarnate in Jesus Christ; and that Jesus Christ is therefore not God, but only, as we say in our loose everyday language, "the very incarnation" of the Divine will of salvation. We see in Him, not God, but only the will of God to save men—and this seems only another way of saying that Christ is not Himself God, but only the love of God is manifested in and through Him. What we get from Seeberg, then, is obviously not a doctrine of the incarnation, but only another form of the prevalent doctrine of Divine indwelling or inspiration, and it is because of this that Seeberg's theory seems to Friedrich Loofs one of the most valuable of those recently promulgated.

In an interesting passage Loofs selects out of the results of recent speculation the three conclusions which he considers the most valuable, and thus reveals to us his own christological conceptions. These are: "First, that the historical person of Christ is looked upon as a human personality; secondly, that this personality, through an indwelling of God or His Spirit, which was unique both before and after, up to the ending of all time, became the Son of God who reveals the Father, and became also the beginner of a new mankind; and, thirdly, that in the future state of perfection a similar indwelling of God has to be realized, though in a copied and therefore secondary form, in all people whom Christ has redeemed." The central point in this statement is that Christ is a man in whom God dwells. "The conviction," remarks Loofs in his explanation of his views, "that God dwelt so perfectly in Jesus through His Spirit as had never been the case before, and never will be till the end of all time, does justice to what we teach historically about Jesus, and may, at the same time, be regarded as satisfactorily expressing the unique position of Jesus, which is a certainty to faith." He is willing to admit, indeed, that he does not quite know what the dwelling of the Spirit of God in Jesus means; and, indeed, he is free to confess that he does not understand even what is meant by the "Spirit of God." And he agrees that the formula of the indwelling of the Spirit of God in Jesus is capable of being taken in so low a sense as to destroy all claim of uniqueness for Jesus. He does not feel so well satisfied with it, therefore, as Hans Hinrich Wendt, for example, expresses himself as being. But he knows nothing better to say, and is willing to leave it at that, with the further acknowledgment that he feels himself face to face here with something of a mystery. Loofs is a Ritschlian of the extreme right wing, and in his sense of a mystery in the person of Christ, leaving him not quite satisfied with the definition of His person as a man in whom God uniquely dwells, we perceive the height of christological conception to which we may attain on Ritschlian presupposition.

What Ritschl himself thought of Christ it is rather difficult to determine; and his followers are not perfectly agreed in their detailed interpretation of it. He himself warns us not to suppose him to be unaware of mysteries because he does not speak of them: it is precisely of the mysteries, he says, that he wishes to preserve silence. Meanwhile he is silent of all that is transcendental in Christ, His pre-existence, His metaphysical Godhead, His exaltation—if these things indeed belong to Christ. If Jesus had any transcendent Being other than His phenomenal Being as man, Ritschl says nothing about it. He seems, indeed, to leave no place for it. He speaks, no doubt, of the "Godhead" of Christ; but by this he means neither to allow that Christ existed as God before He was man, nor to attribute a Divine nature to the historical Christ, nor to suggest that He has now been exalted to Divine glory. He means merely to express his sense that Christ has the value of God for us—that is to say, that we are conscious that we owe salvation to Him. The "Deity" thus predicated to Him, it is explained, is purely "ethical" and not "metaphysical," and, moreover, is transferable to His people so that His Church, viewed as the sphere of His influence, is as Divine as He is. It is the "calling" of Christ to be the founder of the Kingdom of God; and in fulfilling this "calling" He fulfils the eternal purpose of God for the world and mankind. And it is only because His personal will is thus one with the will of God that the predicate of Godhead belongs to Him. "Christ is God" with Ritschl—thus S. Faut sums up the matter—"so far as He is on the one side the executor, on the other the object of the Divine will." It all comes, we see, at the best, to the conception that Jesus is the unique Revealer of God and Mediator of Redemption; and it is in these ideas that the higher class of Ritschlian thinkers live and move and have their being. To them Jesus is indeed purely human—"mere, man" if you will, though the adjective "mere" is objected to as belittling. On the other hand, however, he stands in a unique relation to God "as the embodiment of God's life in humanity, and the guarantor of its presence and power; in whom God verifies Himself to us as Father and Redeemer." There is indeed no metaphysical Sonship with the Father in question; Sonship is an ethico-religious idea when applied to Jesus. When we call Him Son, we do not mean to declare Him God in a metaphysical sense; we but indicate "His superior mission for humanity as representing and communicating the Father's life." By His "centrality for the whole human race, as the one perfect mediator of the Divine life," He is so identified with God that those who have seen Him may be said to have seen the Father also. Through Him and Him only indeed has the Father ever been seen; in. Him alone is "manifested the Father's ideal of humanity and the Father's purpose of grace toward the sinful." Through Him alone have men or can men come to the knowledge of the Father and to true and full communion with Him. "He is the one supreme Revealer," and "not only utters the thought of God"—who thus speaks through Him—but "incarnates the life of God, which through Him communicates itself to mankind as a redeeming and renewing power."

It is thus, we say, that the highest class of Ritschlian thinkers conceive of Jesus. We must emphasize, however, the words "the highest class." For this sketch of their thought of Jesus goes fairly to the limit of what can be said of Christ's dignity on Ritschlian ground. It not only, of course, gives expression to views which would be deemed impossible by a Schultz, a Harnack, a Wendt, but it transcends also what a Kaftan, a Kattenbusch, a Loofs, a Bornemann might be willing to say. For the whole Ritschlian school Christ is not so much Himself God as the means by which God is made known to us, and the instrument through which we are brought to God—and it is therefore only that they are willing, in a modified sense, to call Him Divine. "The term Divinity, applied to Jesus, expresses at bottom" in Ritschl's usage, says a careful expositor of his thought, "nothing more than the absolute confidence of the believer in the redemptive power of the Saviour." "The Godhead of Christ, therefore," says Gottschick, it expresses the value which the historical reality of this personal life possesses, as the power that produces the new humanity of regenerate and reconciled children of God." It is common, indeed, for Ritschlians, like Herrmann, to repudiate altogether experience of the power of the exalted Christ, and to suspend everything on the impression made by "the historical Christ,"—and often, like Otto Ritschl, they mediate this through the Church to such an extent that Jesus appears merely as the starting-point of a movement propagated through the years from man to man; and He may therefore, without fatal loss, be lost sight of altogether. The Ritschlian conception of Christ must take its place as merely another of the numerous forms which the Humanitarianism of our anti-supernaturalistic age manifests.

For the characterizing feature of recent theories of the person of Christ is that they are all humanitarian. The Kenotic theory, which tried to find a middle ground between the God-man and the merely-man Jesus, having passed out of sight, the field is held by pure Humanitarianism. The situation is very clearly revealed in the classification of the possible christological "schematizations" which Otto Kirn gives us in his "Elements of Evangelical Dogmatics." There are only four varieties of Christology, he tells us, which we need bear in mind as we pass our eye down the labours in this field of all the Christian centuries. These are, in his nomenclature, the Trinitarian, the Kenotic, the Messianic, and the Prophetic Christologies. The former two—the Trinitarian and the Kenotic—allow for a God-man; the first in fact, the second in theory. They are theories of the past. Only the Messianic and the Prophetic are living theories of to-day; and both of these give us merely a man Jesus. They differ only in one respect. Whereas in the Messianic Christology no less than in the Prophetic, Jesus in His self-consciousness as well as in His essential nature belongs to humanity and to humanity only, He is yet held in the Messianic Christology to be God's absolute organ for carrying out His counsel of salvation, and to be endowed for His work by a communication of the Holy Spirit beyond measure, fitting Him for unity with God and constituting Him the head of the community of God. The Prophetic Christology, on the other hand, looks upon Him as merely a religious genius, who in reaction upon His environment has become the unrivalled model of piety and as such the supreme guide to humanity in the knowledge of God and in the religious life. We may conceive of Jesus as the God-endowed man, or as the God-discovering man. In the former case we may see in Him God reaching down to man, to do him good: in the latter man reaching up to God, seeking good. Between these two conceptions we may take our choice: beyond them self-styled "modern thought" will not let us go.

Whether this reduction of Jesus to the dimensions of a mere man marks the triumph of modern christological speculation, or its collapse, is another question. The reduction of Jesus to the dimensions of a mere man was a phase of thought concerning His person which required to be fully exploited. And in that sense a service has been done to Christian thinking by the richness and variety of modern humanitarian constructions. Surely by now every possible expedient has been tried. The result is not encouraging. To him who would fain think of Him as merely a man, Jesus Christ looms up in history as ever more and more a mystery; a greater mystery than the God-man who is discarded in His favour. Say that the union of God and man in one person is intrinsically an incomprehensive mystery. It is nevertheless a mystery which, if it cannot be itself explained, yet explains. Without it, everything else is an incomprehensible mystery: the whole developing history of the kingdom of God, the gospel-record, the great figure of Paul and his great christological conceptions, the rise and growth and marvellous power of nascent Christianity, the history of Christianity in the world, the history of the world itself for two thousand years—your regenerated life and mine, our changed hearts and lives, our assurance of salvation, our deathless hope of eternal life. And yet we are invited to believe Him to have been a mere man, on no other ground than that it is easier to believe him to have been a mere man than a God-man! For that, after all, is what the whole ground of the assertion that Jesus was a mere man ultimately reduces to. It is intrinsically easier to believe in the existence of a mere man than in the existence of a God-man. But is it possible to believe that all that has issued from Jesus Christ could issue from a mere man? Apart from every other consideration, does there not lie in the effects wrought by Him an absolute bar to all humanitarian theories of His Person? The humanitarian interpretation of the Person of Christ is confronted by enormous historical and vital consequences, impossible of denial, which apparently spring from a fact which it pronounces inconceivable; though, apart from this fact, these consequences appear themselves to be impossible of explanation.