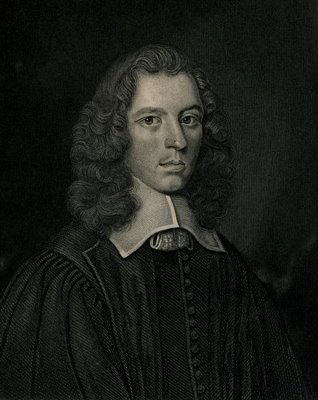

by Stephen Charnock

by Stephen Charnock

And God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually.—Genesis 6:5.

I KNOW not a more lively description in the whole book of God of the natural corruption derived from our first parents, than these words; wherein you have the ground of that grief, which lay so close to God's heart, (verse 6,) and the resolve thereupon to destroy man, and whatsoever was serviceable to that ungrateful creature. That must be highly offensive which moved God to repent of a fabric so pleasing to him at the creation; every stone in the building being at the first laying pronounced "good" by him; and upon a review, at the finishing the whole, he left it the same character with an emphasis, "very good." (Gen. 1:31.) There was not a pin in the whole frame but was very "beautiful;" (Eccles. 3:11;) and being wrought by Infinite "Wisdom," it was "a very comely piece of art."* (Psalm 104:24.) "What, then, should provoke him to repent of so excellent a work?" "The wickedness of man," which "was great in the earth." "How came it to pass that man's wickedness should swell so high? Whence did it spring?" From the "imagination." "Though these might be sinful imaginations, might not the superior faculty preserve itself untainted?" Alas! that was defiled; the "imagination of the thoughts was evil." "But though running thoughts might wheel-about in his mind, yet they might leave no stamp or impression upon the will and affections." Yes, they did: the "imagination of the thoughts of his heart was evil." "Surely all could not be under such a blemish: were there not now and then some pure flashes of the mind?" No, not one: "Every imagination." "But granting that they were evil, might there not be some fleeting good mixed with them, as a poisonous toad hath something useful?" No: "Only evil!" "Well, but there might be some intervals of thinking; and though there was no good thought, yet evil ones were not always rolling there." Yes, they were "continually;" not a moment of time that man was free from them. One would scarce imagine such an inward nest of wickedness; but God hath affirmed it; and if any man should deny it, his own heart would give him the lie.

Let us now consider the words by themselves:—

יֵצֶר "Imagination," properly signifies figmentum, of יָצַר "to afflict, press, or form a thing by way of compression." And thus it is a metaphor taken from a potter's framing a vessel, and extends to "whatsoever is framed" inwardly in the heart, or outwardly in the work. It is usually taken by the Jews for that fountain of sin within us. Mercer tells us, it is always used in an evil sense.† But there are two places, if no more, wherein it is taken in a good sense: Isai. 26:3: יֵצֶר סָמוּךְ "Whose mind is stayed;" and 1 Chron. 29:18, where David prays, that a disposition to offer willingly to the Lord might be preserved "in the imagination of the thoughts of the heart of the people." Indeed, for the most part it is taken for "the evil imaginations" of the heart, as Deut. 31:21; Psalm 81:12, &c. The Jews make a double "figment," a good and bad; and fancy two angels assigned to man, one bad, another good; which Maimonides interprets to be nothing else but natural corruption and reason.‡ This word "imagination" being joined with "thoughts," implies not only the complete thoughts, but the first motion or formation of them, to be evil.

The word "heart" is taken variously in scripture. It signifies properly that inward member which is the seat of the vital spirits: but sometimes it signifies, 1. The understanding and mind.—Psalm 12:2: "With a double heart do they speak;" that is, with a double mind. See also Prov. 8:5. 2. For the will.—2 Kings 10:30: "All that is in my heart," that is, in my will and purpose. 3. For the affections.—As, Deut. 6:5: "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thine heart;" that is, with all thy affections. 4. For conscience.—2 Sam. 24:10: "David's heart smote him;" that is, his conscience checked him. But "heart" here is used for the whole soul, because—according to Pareus's note—the soul is chiefly seated in the heart, especially the will, and the affections, her attendants; because, when any affection stirs, the chief motion of it is felt in the heart. So that, by the "imaginations of the thoughts of the heart" are here meant all the inward operations of the soul, which play their part principally in the heart; whether they be the acts of the understanding, the resolutions of the will, or the blusterings of the affections.

Only evil—The Vulgar mentions not the exclusive particle רַק, and so enervates the sense of the place. But our neighbour-translations either express it as we do, "only;" or to that sense, that they were "certainly," or, "no other than, evil."

Continually—The Hebrew, כָל־הַיוֹם "all the day," or, "every day." Some translations express it verbatim as the Hebrew. Not a moment of a man's life wherein our hereditary corruption doth not belch-out its froth, even "from his youth," (as God expounds it, Gen. 8:21,) to the end of his life.

Whether we shall refer the general wickedness of the heart in the text to that age, as some of the Jesuits do, because after the deluge God doth not seem so severely to censure it; (Gen. 8:21;) or rather take the exposition [which] the learned Rivet gives of it, referring the first part of the verse ("And God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth") to those times; and the second part to the universal corruption of man's nature, and the root of all sin in the world;* the Jesuits' argument will not be very valid, for the extenuation of original corruption, from Gen. 8:21. For if man's imaginations be "evil from his youth," what is it but in another phrase to say they were so "continually?" But, suppose it be understood of the iniquity of that age, may it not be applied to all ages of the world? David complains of the wickedness of his own time, Psalm 14:3; 5:9; yet St. Paul applies it to all mankind, Rom. 3:12, 13. Indeed it seems to be a description of man's natural pravity, by God's words after the deluge, Gen. 8:21, which are the same in sense, to show that man's nature, after that destroying judgment, was no better than before. Every word is emphatical, exaggerating man's defilement: wherein consider the universality, 1. Of the subject: "Everyman." 2. Of the act: "Every thought." 3. Of the qualification of the act: "Only evil." 4. Of the time: "Continually."

The words thus opened afford us this proposition:

"That the thoughts and inward operations of the souls of men are naturally, universally evil and highly provoking."

Some by "cogitation" mean not only the acts of the understanding, but those of the will, yea, and the sense too. But indeed that which we call "cogitation," or "thought," is the work of the mind; "imagination," of the fancy.† It is not properly thought, till it be wrought by the understanding; because the fancy was not a power designed for thinking, but only to receive the images impressed upon the sense, and concoct them, that they might be fit matter for thoughts; and so it is the exchequer, wherein all the acquisitions of sense are deposited, and from thence received by the intellective faculty. So that thoughts are inchoativè in the fancy, consummativè in the understanding, terminativè in all the other faculties. Thought first engenders opinion in the mind; thought spurs the will to consent or dissent; it is thought also which spirits the affections.

I will not spend time to acquaint you with the methods of their generation. Every man knows he hath a thinking faculty, and some inward conceptions, which he calls "thoughts;" he knows that he thinks, and what he thinks; though he be not able to describe the manner of their formation in the womb, or remember it any more than the species of his own face in a glass.

In this discourse let us first see what kind of thoughts are sins.

I. NEGATIVELY. A simple apprehension of sin is not sinful.—Thoughts receive not a sinfulness barely from the object: that may be unlawful to be acted which is not unlawful to be thought-of. Though the will cannot will sin without guilt, yet the understanding may apprehend sin without guilt; for that doth no more contract a pollution by the bare apprehension, than the eye doth by the reception of the species of a loathsome object. Thoughts are morally evil, when they have a bad principle, want a due end, and converse with the object in a wrong manner. Angels cannot but understand the offence which displaced the apostate stars from heaven; but they know not sin cognitione practicâ ["with a practical cognizance"]. Glorified saints may consider their former sins, to enhance their admirations of pardoning mercy. Christ himself must needs understand the matter of the devil's temptation; yet Satan's suggestions to his thoughts were as the vapours of a jakes mixed with the sun-beams, without a defilement of them. Yea, God himself, who is infinite purity, knows the object of his own acts, which are conversant about sin: as his holiness in forbidding it, wisdom in permitting, mercy in pardoning, and justice in punishing. But thoughts of sin in Christ, angels, and glorified saints, are accompanied with an abhorrency of it, without any combustible matter in them to be kindled by it. As our thoughts of a divine object are not gracious, unless we love and delight in it; so a bare apprehension of sin is not positively criminal, unless we delight in the object apprehended. As a sinful object doth not render our thoughts evil, so a divine object doth not render them good; because we may think of it with undue circumstances, as unseasonably, coldly, &c. And thus there is an imperfection in the best thought a regenerate man hath; for though I will suppose he may have a sudden ejaculation without the mixture of any positive impurity, and a simple apprehension of sin with a detestation of it, yet there is a defect in each of them; because it is not with that raised affection to God, or intense abhorrency of sin, as is due from us to such objects, and whereof we were capable in our primitive state.

II. POSITIVELY. Our thoughts may be branched into first motions, or such that are more voluntary:—

1. First motions.—Those unfledged thoughts and single threads, before a multitude of them come to be twisted and woven into a discourse; such as skip-up from our natural corruption, and sink down again, as fish in a river. These are sins, though we consent not to them; because, though they are without our will, they are not against our nature; but spring from an inordinate frame, of a different hue from what God implanted in us. How can the first sprouts be good, if the root be evil? Not only the thought formed, but the very formation, or first imagination, is evil. Voluntariness is not necessary to the essence of a sin, though it be to the aggravation of it. It is not my will or knowledge which doth make an act sinful, but God's prohibition. Lot's incest was not ushered by any deliberate consent of his will; yet who will deny it to be a sin? since he should have exercised a severer command over himself than to be overtaken with drunkenness, which was the occasion of it. (Gen. 19:33–35.) Original sin is not effectivè voluntary in infants, because no act of the will is exerted in an infant about it; yet it is voluntary subjectivè, because it doth inhœrere voluntati ["inhere in the will"]. These motions may be said to be voluntary negatively, because the will doth not set bounds to them, and exercise that sovereign dominion over the operations of the soul which it ought to do, and wherewith it was at its first creation invested. Besides, though the will doth not immediately consent to them, yet it consents to the occasions which administer such motions; and therefore, according to the rule that causa causœ est causa causati,* may be justly charged upon our score.†

2. Voluntary thoughts.—Which are the blossoms of these motions; such that have no lawful object, no right end, not governed by reason, eccentric, disorderly in their motions, and like the jarring strings of an untuned instrument. The meanest of these floating fancies are sins, because we act not, in the production of them, as rational creatures; and what we do without reason, we do against the law of our creation, which appointed reason for our guide, and the understanding to be το ἡγεμονικον, "the governing power" in our souls.

These may be reduced to three heads: I. In regard of God. II. Of ourselves. III. Of others.

I. In regard of God.

1. Cold thoughts of God.—When no affection is raised in us by them; when we delight not in God, the object of those thoughts, but in the thought itself, and operation of our mind about him, consisting of some quaint notion of God of our own conceiving; this is to delight in the act or manner of thinking, not in the object thought-of: and thus these thoughts have a folly and vanity in them. They are also sinful in a regenerate man, in respect of the faintness of the understanding, not acting with that vigour and sprightliness, nor with those raised and spiritual affections, which the worth of such an object doth require.

2. Debasing conceptions unworthy of God.—Such are called in the Heathen "vain imaginations;" (Rom. 1:21;) διαλογισμοις, their "reasonings about" God; who as they glorified not God as God, so they did not think of God as God, according to the dignity of a Deity. Such a mental idolatry may be found in us, when we dress-up a God according to our own humours, humanize him, and ascribe to him what is grateful to us, though never so base:—Psalm 50:21: "Thou thoughtest that I was altogether such an one as thyself:"—which is a grosser degrading of the Deity, than any representation of him by material images, because it is directly against his holiness, which is his glory, applauded chiefly by the angels, and an attribute which he swears by, as having the greatest regard to the honour of it. (Exod. 15:11; Isai. 6:3; Psalm 89:35.) Such an imagination Adam seemed to have, conceiting God to be so mean a being that he, a creature not of a day's standing, could mount to an equality of knowledge with him.

3. Accusing thoughts of God.—Either of his mercy, as in despair; or of his justice, as too severe, as in Cain. (Gen. 4:13.) Of his providence: Adam conceited, yea, and charged God's providence to be an occasion of his crime: "The woman whom thou gavest to be with me." (Gen. 3:12.) His posterity are no juster to God, when they accuse him as a negligent governor of the world. Psalm 94:11: "The Lord knoweth the thoughts of man, that they are vanity." "What thoughts?" Injurious thoughts of his providence, (verse 7,) as though God were ignorant of men's actions, or, at best, but an idle spectator of all the unrighteousness done in the world, not to "regard it," though he did "see" it. And they in the prophet were of the same stamp, "that said in their heart, The Lord will not do good, neither will he do evil." (Zeph. 1:12.) From such kind of thoughts most of the injuries from oppressors, and murmurings in the oppressed, do arise.

4. Curious thoughts about things too high for us.—It is the frequent business of men's minds to flutter about things without the bounds of God's revelation. Not to be content with what God hath published, is to accuse him, in the same manner as the serpent did to our first parents, of envying us an intellectual happiness: "God doth know that your eyes shall be opened." (Gen. 3:5.) Yet how do all Adam's posterity long after this forbidden fruit!

II. In regard of ourselves.—Our thoughts are proud, self-confident, self-applauding, foolish, covetous, anxious, unclean, and what not?

1. Ambitious.—The aspiring thought of the first man runs in the veins of his posterity. God took notice of such strains in the king of Babylon, when he said in his heart, "I will exalt my throne above the stars of God: I will ascend above the heights of the clouds; I will be like the Most High," (Isai. 14:13, 14.) No less a charge will they stand under that settle themselves upon their own bottom, "establish their own righteousness," and will "not submit themselves unto the righteousness of God's" appointment. (Rom. 10:3.) The most forlorn beggar hath sometimes thoughts vast enough to grasp an empire.

2. Self-confident.—Edom's thoughts swelled him into a vain confidence of a perpetual prosperity. Obad. 3: "That saith in his heart, Who shall bring me down to the ground?" And David sometimes said, in the like state, that he should never be moved.

3. Self-applauding.—Either in the vain remembrances of our former prosperity, or ascribing our present happiness to the dexterity of our own wit. Such flaunting thoughts had Nebuchadnezzar at the consideration of his settling Babylon, the head and metropolis of so great an empire. Dan. 4:30: "Is not this great Babylon, that I have built for the house of the kingdom?" &c. Nothing more ordinary among men than overweening reflections upon their own parts, and thinking of themselves above what they ought to think. (Rom. 12:3.)

4. Ungrounded imaginations of the events of things, either present or future.—Such wild conceits, like meteors bred of a few vapours, do often frisk in our minds. (1.) Of things present.—It is likely Eve foolishly imagined she had brought-forth the Messiah, when she brought-forth a murderer. Gen. 4:1: "I have gotten a man the Lord;" as in the Hebrew, אִישׁ אֶת־יְהֹוָה believing, as some interpret, that she had brought-forth the promised seed. And such a brisk conceit Lamech seems to have had of Noah. (Gen. 5:29.) (2.) Of things to come.—Either in bespeaking false hopes, or antedating improbable griefs. Such are the jolly thoughts we have of a happy estate in reversion, which yet we may fall short of. Haman's heart leaped at the king's question, "What shall be done unto the man whom the king delighteth to honour?" (Esther 6:6;) fancying himself the mark of his prince's favour, without thinking that a halter should soon choke his ambition. Or perplexing thoughts at the fear of some trouble, which is not yet fallen upon us, and perhaps never may. How did David torture his soul by his unbelieving fears, that he should "perish one day by the hand of Saul!" (1 Sam. 27:1.) These forestalling thoughts do really affect us: we often feel caperings in our spirits upon imaginary hopes, and shiverings upon conceited fears. These pleasing impostures, and self-afflicting suppositions, are signs either of an idle or indigent mind, that hath no will to work, or only rotten materials to work upon.

5. Immoderate thoughts about lawful things.—When we exercise our minds too thick, and with a fierceness of affection above their merit; not in subserviency to God, or mixing our cares with dependencies on him. Worldly concerns may quarter in our thoughts; but they must not possess all the room, and thrust Christ into a manger; neither must they be of that value with us, as the law was with David, "sweeter than the honey or the honey-comb."

III. In regard of others.—All thoughts of our neighbour against the rule of charity. Such that "imagine evil in their hearts," God "hates." (Zech. 8:17.) These principally are, 1. Envious.—When we torment ourselves with others' fortunes. Such a thought in Cain, upon God's acceptance of his brother's sacrifice, was the prologue to, and foundation of, that cursed murder. (Gen. 4:5.) 2. Censorious.—Stigmatizing every freckle in our brother's conversation. (1 Tim. 6:4.) 3. Jealous and evil surmises.—Contrary to charity, which "thinketh no evil." (1 Cor. 13:5.) 4. Revengeful.—Such made Haman take little content in his preferments, as long as Mordecai refused to court him. (Esther 5:13.) And Esau thought of "the days of mourning" for his father, that he might be revenged for his brother's deceits. (Gen. 27:41.)

There is no sin committed in the world, but is hatched in one or other of these thoughts. But, beside these, there are a multitude of other volatile conceits, like swarms of gnats, buzzing about us, and preying upon us, and as frequent in their successions as the curlings of the water upon a small breath of wind, one following another close at the heels. The mind is no more satisfied with thoughts than the first matter is with forms; continually shifting one for another, and many times the nobler for the baser; as when, upon the putrefaction of a human body, part of the matter is endued with the form of vermin. Such changeable things are our minds, in leaving that which is good for that which is worse, when they are inveigled by an active fancy and Bedlam affections. This "madness is in the heart of men while they live," (Eccles. 9:3,) and starts a thousand frenzies in a day. At the best, our fancy is like a carrier's bag, stuffed with a world of letters, having no dependence upon one another; some containing business, and others nothing but froth.

In all these thoughts there is a further guilt in three respects; namely, 1. Delight; 2. Contrivance; 3. Re-acting.

1. Delight in them.—The very tickling of our fancy by a sinful motion, though without a formal consent, is a sin, because it is a degree of complacency in an unlawful object; when the mind is pleased with the subject of the thought, as it hath a tendency to some sensual pleasure, and not simply in the thought itself, as it may enrich the understanding with some degree of knowledge. The thought indeed of an evil thing may be without any delight in the evil of it. As philosophers delight in making experiments of poisonous creatures, without delighting in the poison as it is a noxious quality; we may delightfully think of sin without guilt, not delighting in it as sin, but as God, by his wise providential ordering, extracts glory to himself, and good to his creature. In this case, though a sinful act be the material object of this pleasure, yet it is not the formal object; because the delight is not terminated in the sin, but in God's ordering the event of it to his own glory. But an inclination to a sinful motion, as it gratifies a corrupt affection, is sin; because every inclination is a malignant tincture upon the affections, including in its own nature an aversion from God, and testifying sin to be an agreeable object. And, without question, there can be no inclination to any thing, without some degree of pleasure in it; because it is impossible we can incline to that which we have a perfect abhorrency of. Hence it follows, that every inclination to a sinful motion is consensus inchoatus, or a "consent in embryo;" though the act may prove abortive. If we think of any unlawful thing with pleasure, and imagine it either in fieri or facto esse,* it brings a guilt upon us, as if it were really acted. As when upon the consideration of such a man's being my enemy, I fancy robbers rifling his goods, and cutting his throat, and rejoice in this revengeful thought, as if it were really done, it is a great sin; because it testifies an approbation of such a butchery, if any man had will and opportunity to commit it; and though it be a supposition, yet the act of the mind is really the same [as] it would be if the sinful act I think of were performed. Or, when a man conditionally thinks with himself, "I would steal such a man's goods, or kill such a person, if I could escape the punishment attending it," it is as if he did rob and murder him; because there is no impediment in his will to the commission of it, but only in the outward circumstances. Nay, though it be a mere ens intentionale, or rationis,† which is the object of the thought; yet the act of the mind is real, and as significant of the inclination of the soul, as if the object were real too: as, if a man hath an unclean motion at the sight of a picture, which is only a composition of well-mixed and well-ordered colours, or at the appearance of the idea of a beauty framed in his own fancy; it is as much uncleanness as if it were terminated in some suitable object, the hinderance being not in the will, but in the insufficiency of the object to concur in such an act. Now, as the more delight there is in any holy service, the more precious it is in itself and more grateful to God; so, the more pleasure there is in any sinful motion, the more malignity there is in it.

2. Contrivance.—When the delight in the thought grows up to the contrivance of the act, which is still the work of the thinking faculty; when the mind doth brood upon a sinful motion to hatch it up, and invents methods for performance, which the wise man calls "artificial inventions," חִשְׁבֹנוֹת (Eccles. 7:29.) So a learned man interprets διαλογισμοι ῶονηροι, (Matt. 15:19,) of "contrivances of murder, adultery," &c.* And the word signifies properly "reasonings;" when men's wits play the devils in their souls, in inventing sophistical reasons for the commission and justification of their crimes, with a mighty jollity at their own craft. Such plots are the trade of a wicked man's heart. A covetous man will be working in his inward shop from morning till night, to study new methods for gain: (2 Peter 2:14: Καρδιαν γεγυμνασμενην ταις ῶλεονεξιαις· "A heart exercised with covetous practices:") and voluptuous and ambitious persons will draw schemes and models in their fancy of what they would outwardly accomplish: "They conceive mischief, and bring forth vanity, and their belly prepareth deceit." (Job 15:35.) Hence the thoughts are called "the counsels" and "devices of the heart;" (1 Cor. 4:5; Isai. 32:7, 8;) when the heart summons the head, and all the thoughts of it, to sit in debate, as a private junto, about a sinful motion.

3. Re-acting sin after it is outwardly committed.—Though the individual action be transient, and cannot be committed again; yet the idea and image of it, remaining in the memory, may, by the help of an apish fancy, be repeated a thousand times over with a ratified pleasure: as both the features of our friends, and the agreeable conversations we have had with them, may with a fresh relish be represented in our fancies, though the persons were rotten many years ago.

Having thus declared the nature of our thoughts, and the degrees of their guilt, the next thing is, to prove that they are sins.

The Jews did not acknowledge them to be sins, unless they were blasphemous, and immediately against God himself.† Some Heathens were more orthodox, and among the rest Ovid, whose amorous pleasures, one would think, should have smothered such sentiments in him.‡ "The Lord," whose knowledge is infallible, "knoweth the thoughts of men, that they are vanity;" (Psalm 94:11;) yea, and of the wisest men, too, according to the apostle's interpretation, 1 Cor. 3:20. And who were they that "became vain in their imaginations," but the wisest men the carnal world yielded? (Rom. 1:21;) the Grecians, the greatest philosophers; the Egyptians, their tutors; and the Romans, their apes. The elaborate operations of an unregenerate mind are fleshly. (Rom. 8:5–7.) If the whole web be so, needs must every thread. "The thought of foolishness is sin," that is, a foolish thought; not objectively a thought of folly, but one formally so; yea, "an abomination to the Lord." (Prov. 24:9; 15:26.) As good thoughts and purposes are acts in God's account, so are bad ones. Abraham's intention to offer Isaac is accounted as an actual sacrifice: that the stroke was not given, was not from any reluctance of Abraham's will, but the gracious indulgence of God. (Heb. 11:17; James 2:21.) Sarah had a deriding thought; and God chargeth it as if it were an outward laughter and a scornful word. (Gen. 18:12, 15.)* Thoughts are the words of the mind, and as real in God's account as if they were expressed with the tongue.

There are three reasons for the proof of this, that they are sins:—

1. They are contrary to the law.—Which doth forbid the first foamings and belchings of the heart; because they arise from an habitual corruption, and testify a defect of something which the law requires to be in us, to correct the excursions of our minds. Rom. 7:7: "I had not known lust, except the law had said, Thou shalt not covet." Doth not the law oblige man as a rational creature? Shall it then leave that part which doth constitute him rational, to fleeting and giddy fancies? No; it binds the soul as the principal agent, the body only as the instrument. For if it were given only for the sensitive part, without any respect to the rational, it would concern brutes as well as men, which are as capable of a rational command and a voluntary obedience, as man without the conduct of a rational soul. It exacts a conformity of the whole man to God, and prohibits a difformity; and therefore engageth chiefly the inward part, which is most the man. It must, then, extend to all the acts of the man; consequently to his thoughts, they being more the acts of the man than the motions of the body. Holiness is the prime excellency of the law, a title ascribed to it twice in one verse. Rom. 7:12: "Wherefore the law is holy, and the commandment holy, and just, and good." Could it be "holy," if it indulged looseness in the more noble part of the creature? Could it be "just," if it favoured inward unrighteousness? Could it be "good," and useful to man, which did not enjoin a suitable conformity to God, wherein the creature's excellency lies? Can that deserve the title of a spiritual law, that should only regulate the brutish part, and leave the spiritual to an unbounded licentiousness? (Rom. 7:14; James 1:25.) Can perfection be ascribed to that law, which doth countenance the unsavoury breathings of the spirit, and lay no stricter an obligation upon us than the laws of men? (Matt. 5:28.) Must not God's laws be as suitable to his sovereignty, as men's laws are to theirs? Must they not then be as extensive as God's dominion, and reach even to the privatest closets of the heart? It is not for the honour of God's holiness, righteousness, goodness, to let the spirit, which hears more flourishing characters of his image than the body, range wildly about without a legal curb.

2. They are contrary to the order of nature, and the design of our creation.—Whatsoever is a swerving from our primitive nature is sin, or at least a consequent of it. But all inclinations to sin are contrary to that righteousness wherewith man was first endued. Eccles. 7:29: "God hath made man upright; but they have sought out many inventions." Man was created both with a disposition and ability for holy contemplations of God; the first glances of his soul were pure; he came every way complete out of the mint of his infinitely wise and good Creator; and when God pronounced all his creatures "good," he pronounced man "very good" amongst the rest. But man is not now as God created him; he is off from his end; his understanding is filled with lightness and vanity. This disorder never proceeded from the God of order; Infinite Goodness could never produce such an evil frame; none of these loose "inventions" were of God's planting, but of man's seeking. No; God never created the intellective, no, nor the sensitive, part, to play Domitian's game, and sport itself in the catching of flies. "Man that is in honour, and understandeth not" that which he ought to understand, and thinks not that which he ought to think, "is like the beasts that perish." (Psalm 49:20.) He plays the beast, because he acts contrary to the nature of a rational and immortal soul. And such brutes we all naturally are, since the first woman believed her sense, her fancy, her affection, in their directions for the attainment of wisdom, without consulting God's law, or her own reason. (Gen. 3:6.) The fancy was bound by the right of nature to serve the understanding: it is then a slighting [of] God's wisdom to invert this order, in making that our governor which he made our subject. It is injustice to the dignity of our own souls to degrade the nobler part to a sordid slavery, in making the brute have dominion over the man; as if the horse were fittest to govern the rider. It is a falseness to God, and a breach of trust, to let our minds be imposed upon by our fancy in giving it only feathers to dandle, and chaff to feed on, instead of those braver objects it was made to converse withal.

3. We are accountable to God and punishable for thoughts.—Acts 8:22: "If perhaps the thought of thine heart may be forgiven thee." Nothing is the meritorious cause of God's wrath, but sin. The text tells us, that they were once the keys which opened the flood-gates of divine vengeance, and broached both the upper and nether cisterns to overflow the world. If they need a pardon, (as certainly they do,) then if mercy doth not pardon them, justice will condemn them. And it is absolutely said, that "a man of wicked devices," or "thoughts," God "will condemn." (Prov. 12:2.) אִישׁ מְזִמּוֹת "A man of thoughts," that is, "evil thoughts;" the word being usually taken in an ill sense. It is God's prerogative, often mentioned in scripture, to "search the heart." To what purpose, if the acts of it did not fall under his censure, as well as his cognizance? He "weigheth the spirits," (Prov. 16:2,) in the balance of his sanctuary and by the weights of his law, to sentence them, if they be found too light. The word doth discover, and judge them; it "divides asunder the soul and spirit," the sensitive part—the affections; and the rational—the understanding and will; both which it doth dissect and open, and judge the acts of them, even "the thoughts and intents," ενθυμησεων και εννοιων, "whatsoever is within the θυμος, and whatsoever is within the νους," the one referring to "the soul," the other to "the spirit." These it passeth a judgment upon; as "a critic," κριτικος, censures the errata even to syllables and letters, in an old manuscript. (Heb. 4:12, 13.) These we are "to render an account of," as the Syriac renders those words, (verse 13,) "With whom we have to do." "Of what?" Of the first bubblings of the heart,—"the notions and intents" of it. The least speck and atom of dust in every chink of this little world is known and censured by God. If our thoughts be not judged, God would not be a righteous Judge. He would not judge according to the merit of the cause, if outward actions were only scanned, without regarding the intents, wherein the principle and end of every action lies, which either swell or diminish the malignity of it. Actions, in kind the same, may have different circumstances in the thoughts, to heighten the one above the other; and if they were only judged, the most painted hypocrite might commence a blessed spirit at last, as well as the exactest saint. It is necessary also for the glory of God's omniscience. It is hereby chiefly that the extensiveness of God's knowledge is discovered, and that in order to "the praise" or dispraise of men; namely, to their justification or condemnation. (1 Cor. 4:5.) Those very thoughts will accuse thee before God's tribunal, which accuse thee here before conscience, his deputy. Rom. 2:15, 16: "Their thoughts the mean while" (that is, in this life, while conscience bears witness) "accusing or else excusing one another; in the day when God shall judge the secrets of men;" that is,—and also at the day of judgment, when conscience shall give-in its final testimony, upon God's examination of the secret counsels. This place is properly meant of those reasonings concerning good and evil in men's consciences, agreeable to the law of nature imprinted on them, which shall "excuse" them, if they practise accordingly, or "accuse" them, if they behave themselves contrary thereunto. But it will hold in this case; for if those inward approbations of the notions of good and evil will accuse us for our contrary practices, they will also accuse us for our contrary thoughts. Our good thoughts will be our accusers for not observing them, and our bad thoughts will be indictments against us for complying with them. It is probable, the soul may be bound-over to answer chiefly for these at the last day;* for the apostle chargeth Simon's guilt upon his "thought," not his word; and tells him, pardon must be principally granted for that. (Acts 8:22.) The tongue was only an instrument to express what his heart did think, and would have been wholly innocent, had not his thoughts been first criminal. What, therefore, is the principal subject of pardon, would be so of punishment; as the first incendiaries in a rebellion are most severely dealt with. And if, as some think, the fallen angels were stripped of their primitive glory only for a conceived thought, how heinous must that be which hath enrolled them in a remediless misery!*

Having proved that there is a sinfulness in our thoughts, let us now see what provocation there is in them; which in some respects is greater than that of our actions. But we must take actions here in sensu diviso, as distinguished from the inward preparations to them. In the one, there is more of scandal; in the other, more of odiousness to God. God indeed doth not punish thoughts so visibly, because, as he is Governor of the world, his judgments are shot against those sins that disturb human society; but he hath secret and spiritual judgments for these, suitable to the nature of the sins.

Now thoughts are greater,

1. In respect of fruitfulness.—"The wickedness" that "God saw great in the earth" was the fruit of "imaginations." They are the immediate causes of all sin. No cockatrice but was first an egg. It was a thought to be "as God," that was the first breeder of all that sin under which the world groans at this day; for Eve's mind was first "beguiled" in the alteration of her thought. (Gen. 3:5; 2 Cor. 11:3.) Since that, the lake of inward malignity acts all its evil by these smoking steams. "Evil thoughts" lead the van in our Saviour's catalogue, (Matt. 15:19,) as that which spirits all the black regiment which march behind. As good motions, cherished, will spring-up in good actions; so loose thoughts, favoured, will break-out in visible plague-sores, and put fire unto all that wickedness which lies habitually in the heart, as a spark may to a whole stock of gunpowder. The "vain babblings" of the soul, as well as those of the tongue, "will increase unto more ungodliness." (2 Tim. 2:16.) Being thus the cause, they include virtually in them all that is in the effect; as a seed contains in its little body the leaves, fruit, colour, scent, which afterward appear in the plant. The seed includes all; but the colour doth not virtually include the scent, or the scent the colour, or the leaves the fruit: so it is here, one act doth not include the formal obliquity of another; but the thought which causeth it doth seminally include both the formal and final obliquity of every action; both that which is in the nature of it, and in the end to which it tends. As, when a tradesman cherisheth immoderate thoughts of gain, and, in the attaining [of] it, runs "into many foolish and hurtful lusts;" (1 Tim. 6:9;) there is cheating, lying, swearing, to put-off the commodity; all these several acts have a particular sinfulness in the nature of the acts themselves, beside the tendency they have to the satisfying an inordinate affection; all which are the spawn of those first immoderate thoughts stirring-up greedy desires.

2. In respect of quantity.—"Imaginations" are said to be "continually evil." There is an infinite variety of conceptions—as the Psalmist speaks of the sea: "Wherein are things creeping innumerable, both small and great;" (Psalm 104:25;) and a constant generation of whole shoals of them;—that you may as well number the fish in the sea, or the atoms in the sun-beams, as recount them.

There is a greater number in regard of the acts, and in regard of the objects.

1. In regard of the acts of the mind:—

(1.) Antecedent acts.—How many preparatory motions of the mind are there to one wicked external act! Yea, how many sinful thoughts are twisted together to produce one deliberate sinful word! All which have a distinct guilt, and, if weighed together, would outweigh the guilt of the action abstractedly considered. How many repeated complacencies in the first motion, degrees of consent, resolved broodings, secret plottings, proposals of various methods, smothering contrary checks, vehement longings, delightful hopes, and forestalled pleasures, in the design!* all which are but thoughts assenting or dissenting in order to the act intended. Upon a dissection of all these secret motions by the critical power of the word, we should find a more monstrous guilt than would be apparent in the single action for whose sake all these spirits were raised. There may be no sin in a material act, considered in itself, when there is a provoking guilt in the mental motion. A hypocrite's religious services are materially good, but poisoned by the imagination skulking in the heart, that gave birth unto them. It is "the wicked mind" or "thought" [that] makes the "sacrifice" (a commanding duty) "much more an abomination" to the Lord. (Prov. 21:27: בְזִמָּה "With a wicked thought.")

(2.) Consequent acts.—When a man's fancy is pregnant with the delightful remembrance of the sin that is past, he draws-down a fresh guilt upon himself, (as they did in the prophet, Ezek. 23:3, 19: "Yet she multiplied her whoredoms, in calling to remembrance the days of her youth," &c. Verse 21: "the lewdness of thy youth,") in reviving the concurrence of the will to the act committed, making the sensual pleasure to commence spiritual, and, if ever there were an aching heart for it, revoking his former grief by a renewed approbation of his darling lust. Thus the sin of thoughts is greater in regard of duration. A man hath neither strength nor opportunity always to act; but he may always think, and imagination can supply the place of action. Or if the mind be tired with sucking one object, it can, with the bee, presently fasten upon another. Senses are weary, till they have a new recruit of spirits; as the poor horse may sink under his burden, when the rider is as violent as ever. Thus old men may change their outward profaneness into mental wickedness; and as the Psalmist remembered his old songs, (Psalm 77:5, 6,) so they their calcined sins in the night, with an equal pleasure. So that, you see, there may be a thousand thoughts as ushers and lacqueys to one act, as numerous as the sparks of a new-lighted fire.

2. In regard of the objects [which] the mind is conversant about.—Such thoughts there are, and attended with a heavy guilt, which cannot probably, no, nor possibly, descend into outward acts. A man may, in a complacent thought, commit fornication with a woman in Spain; in a covetous thought, rob another in the Indies; and in a revengeful thought, stab a third in America; and that while he is in this congregation. An unclean person may commit a mental folly with every beauty he meets. A covetous man cannot plunder a whole kingdom, but in one twinkling of a thought he may wish himself the possessor of all the estates in it. A Timon, a μισανθρωπος, ["misanthrope,"] cannot cut the throats of all the world; but, like Nero, with one glance of his heart he may chop-off the heads of all mankind at a blow. Ambitious men's practices are confined to a small spot of land; but with a cast of his mind he may grasp an empire as large as the four monarchies. A beggar cannot ascend a throne; but in his thoughts he may pass the guards, murder his prince, and usurp the government. Nay, further: an atheist may think "there is no God," (Psalm 14:1,) that is, as some interpret it, wish there were no God, and thus in thought undeify God himself; though he may sooner dash heaven and earth in pieces than accomplish it. The body is confined to one object, and that narrow and proportionable to its nature; but the mind can wing itself to various objects in all parts of the earth. Where it finds none, it can make one; for fancy can compact several objects together, coin an image, colour a picture, and commit folly with it, when it hath done; it can nestle itself in cobwebs spun out of its own bowels.

3. In respect of strength.—Imaginations of the heart are "only," that is, purely, "evil." The nearer any thing is in union with the root, the more radical strength it hath. The first ebullitions of light and heat from the sun are more vigorous than the remoter beams; and the steams of a dunghill more noisome next that putrified body, than when they are dilated in the air. Grace is stronger in the heart-operations than in the outward streams; and sin more foul in the imagination of the thoughts of the heart, than in the act. In the text, the outward wickedness of the world is passed-over with a short expression; but the Holy Ghost dwells upon the description of the wicked "imagination," because there lay the mass. Man's "inward part is very wickednesses," קִרְבָּם הַוקִרְבָּם הַוֹּותּוֹת (Psalm 5:9,) a whole nest of vipers. Thoughts are the immediate spawn of the original corruption, and therefore partake more of the strength and nature of it. Acts are more distant, being the children of our thoughts, but the grandchildren of our natural pravity. Besides, they lie nearest to that wickedness in the inward part, sucking the breast of that poisonous dam that bred them. The strength of our thoughts is also reinforced by being kept-in, for want of opportunity to act them; as liquors in close glasses ferment and increase their sprightliness. "Musing," either carnal or spiritual, makes "the fire burn" the hotter; (Psalm 39:3;) as the fury of fire is doubled by being pent in a furnace. Outward acts are but the sprouts; the sap and juice lie in the wicked imagination or contrivance, which hath a strength in it to produce a thousand fruits as poisonous as the former. "The members" are the "instruments," or "weapons," ὁπλα, "of unrighteousness:" (Rom. 6:13:) now, the whole strength which doth manage the weapon lies in the arm that wields it; the weapon of itself could do no hurt without a force impressed. Let me add this too, that sin in thoughts is more simply sin. In acts there may be some occasional good to others; for a good man will make use of the sight of sin committed by others to increase his hatred of it; but in our sinful thoughts there is no occasion of good to others, they lying locked-up from the view of man.

4. In respect of alliance.—In these we have the nearest communion with the devil. The understanding of man is so tainted, that his "wisdom," the chiefest flower in it, is not only "earthly" and "sensual," (it were well if it were no worse!) but "devilish" too. (James 3:15.) If the flower be so rank, what are the weeds? Satan's "devices" and our "thoughts" are of the same nature, and sometimes in scripture expressed by the same word, νοηματα. (2 Cor. 2:11; 10:5.) As he hath his devices, so have we, against the authority of God's law, the power of the gospel, and the kingdom of Christ. The devils are called "spiritual wickednesses," (Eph. 6:12,) because they are not capable of carnal sins. Profaneness is an uniformity with the world, and intellectual sins are an uniformity with the god of it. (Eph. 2:2, 3.) In verse 3 there is a double walking, answerable to a double pattern in verse 2: "Fulfilling the desires of the flesh" is a walking "according to the course of this world," or making the world our copy; and fulfilling the desires of the mind" is a walking "according to the prince of the power of the air," or a making the devil our pattern. In carnal sins Satan is a tempter, in mental an actor. Therefore, in the one, we are conformed to his will; in the other, we are transformed into his likeness. In outward, we evidence more of obedience to his laws; in inward, more of affection to his person, as all imitations of others are. Therefore there is more of enmity to God, because more of similitude and love to the devil; a nearer approach to the diabolical nature implying a greater distance from the divine. Christ never gave so black a character as that of "the devil's children" to the profane world, but to the Pharisees, who had left the sins of men, to take-up those of devils, and were most guilty of those "high imaginations" which ought to be brought "into captivity to the obedience of Christ."

5. In respect of contrariety and odiousness to God.—"Imaginations" were "only evil;" and so most directly contrary to God, who is only good. Our natural "enmity against God" is seated in "the mind." (Rom. 8:7.) The sensitive part aims at its own gratification, and in men's serving their lusts they serve their pleasures: ("Serving divers lusts and pleasures;" Titus 3:3:) but the το ἡγεμονικον, "the prince" in man is possessed with principles of a more direct contrariety; whence it must follow, that all the thoughts and counsels of it are tinctured with this hatred. They are, indeed, a defilement of the higher part of the soul, and that which belongs more peculiarly to God; and the nearer any part doth approach to God, the more abominable is a spot upon it; as to cast dirt upon a prince's house, is not so heinous as to deface his image. The understanding, the seat of thoughts, is more excellent than the will; both because we know and judge before we will, and we will, or ought to will, only so much as the understanding thinks fit to be willed; and because God hath bestowed the highest gifts upon it, adorning it with more lively lineaments of his own image. Col. 3:10: "Renewed in knowledge after the image of him that created him;" implying that there was more of the image of God at the first creation bestowed upon the understanding, the seat of knowledge, than on any other part, yea, than on all the bodies of men distilled together. "Father of spirits" is one of God's titles: (Heb. 12:9:) to bespatter his children, then, so near a relation, the jewel that he is choice of, must needs be more heinous. He being "the Father of spirits," this "spiritual wickedness" of nourishing evil thoughts is a cashiering all child-like likeness to him. The traitorous acts of the mind are most offensive to God; as it is a greater despite for a son to whom the father hath given the greater portion, to shut him out of his house, only to revel in it with a company of roisters and strumpets, than in a child who never was so much the subject of his father's favour. And it is more heinous and odious, if these thoughts which possess our souls be at any time conversant about some idea of our own framing. It were not altogether so bad, if we loved something of God's creating, which had a physical goodness and a real usefulness in it to allure us; but to run wildly to embrace an ens rationis, to prefer "a thing of" no existence but what is coloured by our own "imagination," of no virtue, no usefulness, a thing that God never created nor pronounced good,—is a greater enmity and a higher slight of God.

6. In respect of connaturalness and voluntariness.—They are "the imaginations of the thoughts of the heart," and they are "continually evil." They are as natural as the æstuations of the sea, the bubblings of a fountain,* or the twinklings of the stars. The more natural any motion is, ordinarily the quicker it is. Time is requisite to action; but "thoughts have an instantaneous motion." The body is a heavy piece of clay; but "the mind can start-out on every occasion."† Actions have their stated times and places; but these solicit us and are entertained by us at all seasons. Neither day nor night, street nor closet, exchange nor temple, can privilege us from them: we meet them at every turn, and they strike upon our souls as often as light upon our eyes. There is no restraint for them: the laws of men, the constitution of the body, the interest of profit or credit, are mighty bars in the way of outward profaneness; but nothing lays the reins upon thoughts, but "the law of God;" and this man "is not subject to, neither can be." (Rom. 8:7.) Besides, the natural atheism in man is a special friend and nurse of these, few firmly believing either the omniscience of God, or his government of the world; which the scripture speaks of frequently, as the cause of most sins among the sons of men. (Isai. 29:15; Ezek. 9:9; Job 22:13, 14.) Actions are done with some reluctance, and nips of natural conscience. Conscience will start at a gross temptation; but it is not frighted at thoughts. Men may commit speculative folly, and their conscience look on, without so much as a nod against it: men may tear out their neighbours' bowels in secret wishes, and their conscience never interpose to part the fray. Conscience, indeed, cannot take notice of all of them; they are too subtile in their nature, and too quick for the observation of a finite principle. They are many: "There are many devices in a man's heart," (Prov. 19:21,) and they are nimble too; like the bubblings of a boiling pot, or the rising of a wave, that presently slides into its level; and, as Florus saith of the Ligurians, "the difficulty is more to find, than conquer, them."‡ They are secret sins, and are no more discerned than motes in the air, without a spiritual sun-beam; whence David cries out, "Cleanse thou me from secret sins;" (Psalm 19:12;) which some explain of sins of thoughts, that were like sudden and frequent flashes of lightning, too quick for his notice, and unknown to himself. There is also more delight in them. There is less of temptation in them, and so more of election; and consequently more of the heart and pleasure in them, when they lodge with us. Acts of sin are troublesome; there is danger as well as pleasure in many of them: but there is no outward danger in thoughts; therefore the complacency is more compact and free from distraction. The delight is more unmixed, too, as intellectual pleasures are more refined than sensual. All these considerations will enhance the guilt of these inward operations.

USES

The uses shall be two, though many inferences might be drawn from the point.

USE I. REPROOF

What a mass of vanity should we find in our minds, if we could bring our thoughts in the space of one day, yea, but one hour, to an account! How many foolish thoughts with our wisdom, ignorant with our knowledge, worldly with our heavenliness, hypocritical with our religion, and proud with our humiliations! Our hearts would be like a grot, furnished with monstrous and ridiculous pictures; or as the wall in Ezekiel's vision, "portrayed" with "every form of creeping things, and abominable beasts;" a greater abomination than "the image of jealousy at the outward gate of the altar." (Ezek. 8:5, 10.) Were our inwards opened, how should we stand gazing both with scorn and wonder at our being such a pack of fools! Well may we cry out, with Agur, "We have not the understandings of men:" (Prov. 30:2:) we make not the use of them, as is requisite for rational creatures; because we degrade them to attendances on a brutish fancy. I make no question, but were we able to know the fancies of some irrational creatures, we should find them more noble, heroic, and generous, in suo genere, than the thoughts of most men; more agreeable to their natures, and suited to the law of their creation. How little is God in any of our thoughts, according to his excellency! Psalm 10:4: "God is not in all his thoughts." No; our shops, our rents, our backs, and bellies usurp God's room. If any thoughts of God do start-up in us, how many covetous, ambitious, wanton, revengeful thoughts are jumbled together with them! Is it not a monstrous absurdity to place our friend with a crew of vipers, to lodge a king in a sty, and entertain him with the fumes of a jakes and dunghill? "The tongue of the just is as choice silver; the heart of the wicked is little worth;" (Prov. 10:20;) all the peddling wares and works in his inward shop are not valuable* with one silver drop from a gracious man's lips. It was an invincible argument of the primitive Christians for the purity of the Christian religion above all others in the world, that it did prohibit evil thoughts:† and is it not as unanswerable an argument that we are no Christians, if we give liberty to them? What is our moral conversation outwardly, but only a bare abstinence from sin,—not a disaffection? Were we really and altogether Christians, would not that which is the chiefest purity of Christianity be our pleasure? and would we any more wrong God in our secret hearts than in the open streets? Is not thought a beam of the mind? and shall it be enamoured only on a dunghill? Is not the understanding the eye of the soul? and shall it behold only gilded nothings? It is "the flower of the spirit:"* shall we let every caterpillar suck it? It is the queen in us: shall every ruffian deflower it? It is as the sun in our heaven: and shall we besmear it with misty fancies? It was created, surely, for better purposes than to catch a thousand weight of spiders, as Heliogabalus employed his servants.† It was not intended to be made the common sewer of filthiness, or ranked among those ζωα ῶαμφαγα, ["gluttonous animals,"] which eat not only fruit and flesh, but flies, worms, dung, and all sorts of loathsome materials.† Let not, therefore, our minds wallow in a sink of fantastical follies, whereby to rob God of his due, and our souls of their happiness.

USE II. EXHORTATION

We must take care for the suppression of them. All vice doth arise from imagination.§ Upon what stock doth ambition and revenge grow, but upon a false conceit of the nature of honour? What engenders covetousness, but a mistaken fancy of the excellency of wealth? "Thoughts" must be forsaken, as well as our "way;" we cannot else have an evidence of a true conversion: (Isai. 55:7: "Let the wicked forsake his way, and the unrighteous man his thoughts," &c:) and if we do not discard them, we are not likely to have an "abundant pardon;" and what will the issue of that be, but an abundant punishment? Mortification must extend to these: "affections" must be "crucified," (Gal. 5:24,) and all the little brats of thoughts which beget them or are begotten by them. Shall we nourish that which brought down the wrath of God upon the old world, as though there had not been already sufficient experiments of the mischief they have done? Is it not our highest excellency to be conformed to God in holiness, in as full a measure as our finite natures are capable? And is not God holy in his counsels and inward operations, as well as in his works? Hath God any thoughts but what are righteous and just? Therefore, the more foolish and vain our imaginations are, the more are we "alienated from the life of God." The Gentiles were so, because they "walked in the vanity of their mind;" (Eph. 4:17, 18;) and we shall be so, if vanity walk and dwell in ours. As the tenth commandment forbids all unlawful thoughts and desires, so it obligeth us to all thoughts and desires that may make us agreeable to the divine will, and like to God himself. We shall find great advantage by suppressing them: we can more easily resist temptations without, if we conquer motions within. Thoughts are the mutineers in the soul, which set open the gates for Satan; he hath held a secret intelligence with them (so far as he knows them) ever since the fall; and they are his spies, to assist him in the execution of his devices. They prepare the tinder, and the next fiery dart sets all on a flame. Can we cherish these, if we consider that Christ died for them? He shed his blood for that which put the world out of order; which was accomplished by the sinful imagination of the first man, and continued by those imaginations mentioned in the text. He died to restore God to his right, and man to his happiness: neither of which can be perfectly attained, till those be thrown out of the possession of the heart.

That we may do this, let us consider these following directions; which may be branched into these heads: 1. For the raising [of] good thoughts. 2. Preventing bad. 3. Ordering bad, when they do intrude. 4. Ordering good, when they appear in us.

1. For raising good thoughts.

(1.) Get renewed hearts.—The fountain must be cleansed which breeds the vermin. Pure vapours can never ascend from a filthy quagmire. What issue can there be of a vain heart, but vain imaginations? Thoughts will not "become new," till a "man is in Christ." (2 Cor. 5:17.) We must be holy, before we can think holily. Sanctification is necessary for the dislodging of vain thoughts, and the introducing of good. "Wash thy heart from wickedness, that thou mayest be saved. How long shall thy vain thoughts lodge within thee?" (Jer. 4:14.) A sanctified reason would both discover and shame our natural follies. As all animal operations, so all the spiritual motions of our heads, depend upon the life of our hearts, as the principium originis ["the originating principle"]. (Prov. 4:23.) As there is a "law in our members to bring us into captivity to the law of sin," (Rom. 7:23,) so there must be a law in our minds to "bring our thoughts into captivity to the obedience of Christ." (2 Cor. 10:5.) We must "be renewed in the spirit of our minds," (Eph. 4:23,) in our reasonings and thoughts, which are the "spirits" whereby the understanding acts, as the animal spirits are the instruments of corporeal motion. Till the understanding be born of the Spirit, it will delight in, and think of, nothing but things suitable to its fleshly original: but when it is spiritual, it receives new impressions, new reasonings and motions, suitable to the Holy Ghost, of whom it is born. "That which is born of the flesh is flesh; and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit." (John 3:6.) A stone, if thrown upward a thousand times, will fall backward, because it is a forced motion; but if the nature of this stone were changed into that of fire, it would mount as naturally upward as before it sank downward. You may force some thoughts toward heaven sometimes; but they will not be natural, till nature be changed. Grace only gives stability, and prevents fluctuation, by fixing the soul upon God, as its chief end: "It is a good thing that the heart be established with grace:" (Heb. 13:9:) and what is our end will not only be first in our intentions, but most frequent in our considerations. Hence a sanctified heart is called in scripture "a steadfast heart." There must be an enmity against Satan put into our hearts, according to the first promise, before we can have an enmity against his imps, or any thing that is like him.

(2.) Study scripture.—Original corruption stuffs us with bad thoughts, and scripture-knowledge would stock us with good ones; for it proposeth things in such terms as exceedingly suit our imaginative faculty, as well as strengthen our understanding. Judicious knowledge would make us "approve things that are excellent;" (Phil. 1:9, 10;) and where such things are approved, toys cannot be welcome. Fulness is the cause of steadfastness: the cause of an intent and piercing eye is the multitude of animal spirits. Without this skill in the word we shall have as foolish conceits of divine things, as ignorant men without the rules of art have of the sun and stars, or things in other countries which they never saw. The word is called "a lamp to our feet," that is, the affections; "a light to our eyes," that is, the understanding. (Psalm 119:105; 19:8.) It will direct the glances of our minds, and the motions of our affections. It "enlightens the eyes," and makes us have a new prospect of things; as a scholar, [who has] newly entered into logic, and studied the predicaments, &c., looks upon every thing with a new eye and more rational thoughts, and is mightily delighted with every thing he sees, because he eyes them as clothed with those notions he hath newly studied. The devil had not his engines so ready to assault Christ, as Christ from his knowledge had scripture-precepts to oppose him. As our Saviour by this means stifled thoughts offered, so by the same we may be able to smother thoughts arising in us. Converse therefore often with the scripture, transcribe it in your heart, and turn it in succum et sanguinem, ["into nutritious moisture and blood,"] whereby a vigour will be derived into every part of your soul, as there is, by what you eat, to every member of your body. Thus you will make your mind Christ's library, as Jerome speaks of Nepotianus.*

(3.) Reflect often upon the frame of your mind at your first conversion.—None have more settled and more pleasant thoughts of divine things than new converts, when they first clasp about Christ; partly because of the novelty of their state, and partly because God puts a full stock into them; and diligent tradesmen at their first setting-up have their minds intent upon improving their stock. Endeavour to put your mind in the same posture [in which] it was then. Or if you cannot tell the time when you did first close with Christ, recollect those seasons wherein you have found your affections most fervent, your thoughts most united, and your mind most elevated; as when you renewed repentance upon any fall, or had some notable cheerings from God; and consider what matter it was which carried your heart upward, what employment you were engaged in, when good thoughts did fill your soul; and try the same experiment again. Asaph would oppose God's ancient works to his murmuring thoughts: he would remember his "song in the night," that is, the matter of his song, and read over the records of God's kindness. (Psalm 77:6–12.) David too would "never forget," that is, frequently renew the remembrance of, those precepts whereby God had particularly quickened him. (Psalm 119:93.) Yea, he would reflect upon the places, too, where he had formerly conversed with God, to rescue himself from dejecting thoughts: "Therefore will I remember thee from the land of Jordan, and of the Hermonites, from the hill Mizar." (Psalm 42:6.) Some elevations surely David had felt in those places, the remembrance whereof would sweeten the sharpness of his present grief. When our former sins visit our minds, pleading to be speculatively re-acted, let us remember the holy dispositions we had in our repentance for them, and the thankful frames when God pardoned them. The disciples, at Christ's second appearance, reflected upon their own warm temper at his first discourse with them in a disguise, to confirm their faith, and expel their unbelieving conceits: "did not our heart burn within us while he talked with us by the way, and while he opened to us the scriptures?" (Luke 24:32.) Strive to recollect truths, precepts, promises, with the same affection which possessed your souls when they first appeared in their glory and sweetness to you.

(4.) Ballast your heart with a love to God.—David thought "all the day" of God's law, as other men do of their lusts, because he unexpressibly loved it: "O how love I thy law! it is my meditation all the day." (Psalm 119:97.) This was the successful means he used to stifle vain thoughts, and excite his hatred of them: "I hate vain thoughts; but thy law do I love." (Verse 113.) It is the property of love to think no evil: (1 Cor. 13:5:) it thinks good and delightful thoughts of God, friendly and useful thoughts of others. It fixeth the image of our beloved object in our minds, [so] that it is not in the power of other fancies to displace it.* The beauty of an object will fasten a rolling eye: it is difficult to divorce our hearts and thoughts from that which appears lovely and glorious in our minds, whether it be God or the world. Love will, by a pleasing violence,† bind-down our thoughts, and hunt-away other affections: if it doth not establish our minds, they will be like a cork, which, with a fight breath, and a short curl of water, shall be tossed up and down from its station. Scholars that love learning will be continually hammering upon some notion or other which may further their progress, and as greedily clasp it as the iron will its beloved loadstone. He that is "winged with a divine love" to Christ will have frequent glances and flights toward him,‡ and will start-out from his worldly business several times in a day to give him a visit. Love, in the very working, is a settling grace; it increaseth our delight in God, partly by the sight of his amiableness, which is cleared to us in the very act of loving, and partly by the recompences he gives to the affectionate carriage of his creature; both which will stake down the heart from vagaries, or giving entertainment to such loose companions as evil thoughts are. Well, then, if we had this heavenly affection strong in us, it would not suffer unwholesome weeds to grow up so near it; either our love would consume those weeds, or those weeds will choke our love.

(5.) Exercise faith.—As the habit of faith is attended with habitual sanctification, so the acts of faith are accompanied with a progress in the degrees of it. That faith which brings Christ to dwell in our souls, will make us often think of our inmate. Faith doth realize divine things, and make absent objects as present; and so furnisheth fancy with richer streams to bathe itself in than any other principle in the world. As there is a necessity of the use of fancy while the soul is linked to the body, so there is also a necessity of a corrective for it. Reason doth in part regulate it; but it is too weak to do it perfectly, because fancy in most men is stronger than reason: man being the highest of imaginative beings, and the lowest of intelligent, fancy is in its exaltation more than in creatures beneath him, and reason in its detriment more than in creatures above him; and therefore the imagination needs a more skilful guide than reason.* Fancy is like fire, "a good servant, but a bad master;" if it march under the conduct of faith, it may be highly serviceable, and, by putting lively colours upon divine truth, may steal away our affections to it. "Faith is the evidence of things not seen," namely, not by a corporeal, but intellectual, eye; and so it will supply the office of sense. It is "the substance of things hoped for;" (Heb. 11:1;) and if hope be an attendant on faith, our thoughts will surely follow our expectations. The remedy David used, when he was almost stifled with disquieting thoughts, was to excite his soul to a hope and confidence in God: "Why art thou cast down, O my soul? and why art thou disquieted in me? Hope thou in God:" (Psalm 42:5:) and when they returned upon him, he useth the same diversion. (Verse 11.) "The peace of God," that is, the reconciliation made by a Mediator between God and us, believingly apprehended, will "keep," or "garrison," our "hearts and minds," or "thoughts," φρουρησει τα νοηματα ὑμων, against all anxious assaults both from within and without. (Phil. 4:6, 7.) When any vain conceit creeps-up in you, act faith on the intercession of Christ; and consider, "Is Christ thinking of me now in heaven, and pleading for me? and shall I squander away my thoughts on trifles, which will cost me both tears and blushes?" Believingly meditate on the promises; they are a means to cleanse us from the filthiness of the spirit, as well as that of the flesh: "Having therefore these promises, let us cleanse ourselves," &c. (2 Cor. 7:1.) If the having them be a motive, the using them will be a means, to attain this end. "Looking at the things which are not seen," preserves us from fainting, and renews the "inward man day by day." (2 Cor. 4:16, 18.) These invisible things could not well keep our hearts from fainting, if faith did not first keep the thoughts from wandering from them.

(6.) Accustom yourself to a serious meditation every morning.—Fresh airing our souls in heaven will engender in us purer spirits and nobler thoughts. A morning seasoning would secure us for all the day. Though other necessary thoughts about our callings will and must come-in, yet when we have dispatched them, let us attend our morning theme as our chief companion.† As a man that is going with another about some considerable business, (suppose, to Westminster,) though he meets with several friends in the way, and salutes some, and [with] others with whom he hath some affairs he spends a little time, yet he quickly returns to his companion, and both together go their intended stage: do thus in the present case. Our minds are active, and will be doing something, though to little purpose; and if they be not fixed upon some noble object, they will, like madmen and fools, be mightily pleased in playing with straws. The thoughts of God were the first visitors David had in the morning; God and his heart met together as soon as he was awake, and kept company all the day after. (Psalm 139:17, 18.)

In this meditation look both to the matter and manner.

First. Look to the matter of your meditation.—Let it be some truth which will assist you in reviving some languishing grace, or fortify you against some triumphing corruption; for it is our darling sin which doth most envenom our thoughts: "As a man thinketh in his heart, so is he." (Prov. 23:7.) As, if you have a thirst for honour, let your fancy represent the honour of being a child of God and heir of heaven: if you are inclined to covetousness, think of the riches stored up in a Saviour, and dispensed by him; if to voluptuousness, fancy the pleasures in the ways of wisdom here, and at God's right hand hereafter. This is to deal with our hearts as Paul with his hearers, to catch them with guile. Stake your soul down to some serious and profitable mystery of religion; as the majesty of God, some particular attribute, his condescension in Christ, the love of our Redeemer, the value of his sufferings, the virtue of his blood, the end of his ascension, the work of the Spirit, the excellency of the soul, beauty of holiness, certainty of death, terror of judgment, torments of hell, and joys of heaven. The heads of the catechism might be taken in order, which would both increase and actuate our knowledge. Why may not that which was the subject of God's innumerable thoughts be the subject of ours? (Psalm 40:5.) God's thoughts and counsels were concerning Christ, the end of his coming, his death, his precepts of holiness, and promises of life; and that not only speculatively, but with an infinite pleasure in his own glory, and the creature's good, to be accomplished by him. Would it not be work enough for our thoughts all the day, to travel over the length, breadth, height, and depth of the love of Christ? Would the greatness of the journey give us leisure to make any starts out of the way? Having settled the theme for all the day, we shall find occasional assistances even from worldly businesses; as scholars, who have some exercise to make, find helps in their own course of reading, though the book hath no designed respect to their proper theme. Thus, by employing our minds about one thing chiefly, we shall not only hinder them from vain excursions, but make even common objects to be oil to our good thoughts, which otherwise would have been fuel for our bad. Such generous liquor would scent our minds and conversations all the day, [so] that whatsoever motion came into our hearts, would be tinctured with this spirit, and savour of our morning thoughts; as vessels, having been filled with a rich wine, communicate a relish of it to the liquors afterward put into them. We might also more steadily go about our worldly business, if we carry God in our minds; as one foot of the compass will more regularly move about the circumference, when the other remains firm in the centre.

Secondly. Look to the manner of it.

(i.) Let it be intent.—Transitory thoughts are like the glances of the eye,—soon on and soon off; they make no clear discovery, and consequently raise no sprightly affections. Let it be one principal subject, and without flitting from it; for if our thoughts be unsteady, we shall find but little warmth; a burning-glass often shifted fires nothing. We must σκοπουντων, "look," "at the things which are not seen," as wistly as men do at a mark they shoot at. (2 Cor. 4:18.) Such an intent meditation would "change us into the image," and cast us into the mould, of those truths we think of; (2 Cor. 3:18;) it would make our minds more busy about them all the day, as a glaring upon the sun fills our eyes for some time after with the image of it. To this purpose look upon yourselves as deeply concerned in the things you think of. Our minds dwell upon that whereof we apprehend an absolute necessity. A condemned person would scarce think of any thing but procuring a reprieve, and his earnestness for this would bar the door against other intruders.

(ii.) Let it be affectionate and practical.—Meditation should excite a spiritual delight in God, as it did in the Psalmist: "My meditation of him shall be sweet: I will be glad in the Lord:" (Psalm 104:34:) and a divine delight would keep-up good thoughts, and keep-out impertinencies. A bare speculation will tire the soul, and, without application and pressing upon the will and affections, will rather chill than warm devotion. It is only by this means that we shall have the efficacy of truth in our wills, and the sweetness in our affections, as well as the notion of it in our understandings. The more operative any truth is in this manner upon us, the less power will other thoughts have to interrupt, and the more disdainfully will the heart look upon them, if they dare be impudent. Never, therefore, leave thinking of a spiritual subject, till your heart be affected with it. If you think of the evil of sin, leave not till your heart loathe it; if of God, cease not till it mount up in admirations of him. If you think of his mercy, melt for abusing it; if of his sovereignty, awe your heart into obedient resolutions; if of his presence, double your watch over yourself. If you meditate on Christ, make no end till your hearts love him; if of his death, plead the value of it for the justification of your persons, and apply the virtue of it for the sanctification of your natures. Without this practical stamp upon our affections, we shall have light spirits, while we have opportunity to converse with the most serious objects. We often hear foolish thoughts breathing out themselves in a house of mourning, in the midst of coffins and trophies of death, as if men were confident they should never die; whereas none are so ridiculous as to assert they shall live for ever. By this instance in a truth so certainly assented to, we may judge of the necessity of this direction in truths more doubtfully believed.