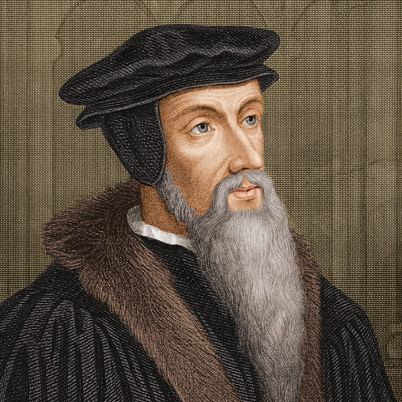

by John Calvin

by John Calvin

1. Indulgences according to Romanist doctrine, and the mischief caused by them

Now indulgences flow from this doctrine of satisfaction. For our opponents pretend that to make satisfaction those indulgences supply what our powers lack. e(a)And they go to the mad extreme of defining them as the distribution of the merits of Christ and the martyrs, which the pope distributes by his bulls. These men are fit to be treated by drugs for insanity2 rather than to be argued with. For it is hardly worth-while to undertake to refute errors so foolish, which under the onslaught of many battering-rams are of themselves beginning to grow old and to show deterioration. eBut because a brief refutation will be useful for certain uninstructed persons, I shall not omit it.

The fact that indulgences have so long stood untouched, and in such unrestrained and furious license have retained such lasting impunity, can truly serve as a proof of how deeply men were immersed for centuries in a deep night of errors. Men saw themselves openly and undisguisedly held up to ridicule by the pope and his bull-bearers, their souls' salvation the object of lucrative trafficking, the price of salvation reckoned at a few coins, nothing offered free of charge. By this subterfuge they saw themselves cheated of their offerings, which were filthily spent on whores, pimps, and drunken revelries. But they also saw that the greatest trumpeters of indulgences hold them in most contempt; that this monster daily runs more riotously and lecherously abroad, and that there is no end; that new lead is daily put forward and new money taken away.3 Yet with the highest veneration they received indulgences, worshiped them as pious frauds by which men could with some profit be deceived. Finally, when the world has ventured to become a little wise, indulgences grow cold and gradually freeze up, until they will altogether vanish.

2. Indulgences contrary to Scripture

Now very many persons see the base tricks, deceits, thefts, and greediness with which the indulgence traffickers have heretofore mocked and beguiled us, and yet they do not see the very fountain of the impiety itself. As a consequence, it behooves us to indicate not only the nature of indulgences but also what in general they would be, wiped clean of all spots. aThe merits of Christ and the holy apostles and martyrs our opponents call the "treasury of the church." They pretend that the prime custody of this storehouse, as I have already hinted, has been entrusted to the Bishop of Rome, who controls the dispensing of these very great benefits, so that he can both distribute them by himself and delegate to others the management of their distribution. Consequently, plenary indulgences, as well as indulgences for certain years, stem from the pope; indulgences for a hundred days, from the cardinals; and of forty days, from the bishops!5

Now these, to describe them rightly, are a profanation of the blood of Christ, a Satanic mockery, to lead the Christian people away from God's grace, away from the life that is in Christ, and turn them aside from the true way of salvation. For how could the blood of Christ be more foully profaned than when they deny that it is sufficient for the forgiveness of sins, for reconciliation, for satisfaction—unless the lack of it, as of something dried up and exhausted, be otherwise supplied and filled? "To Christ, the Law and all the Prophets bear witness," says Peter, that "through him we are to receive forgiveness of sins." [Acts 10:43 p.] Indulgences bestow forgiveness of sins through Peter, Paul, and the martyrs. "The blood of Christ cleanses us from sin," says John [1 John 1:7 p.]. Indulgences make the blood of martyrs the cleansing of sins. "Christ," says Paul, "who knew no sin, was made sin for us" (that is, satisfaction of sin) "so that we might be made the righteousness of God in him" [2 Cor. 5:21 p., cf. Vg.]. Indulgences lodge satisfaction of sins in the blood of martyrs. Paul proclaimed and testified to the Corinthians that Christ alone was crucified and died for them [cf. 1 Cor. 1:13]. Indulgences declare: "Paul and others died for us." Elsewhere Paul says, "Christ acquired the church with his own blood." [Acts 20:28 p.] Indulgences establish another purchase price in the blood of martyrs. "By a single offering Christ has perfected for all time those who are sanctified." [Heb. 10:14.] Indulgences proclaim: Sanctification, otherwise insufficient, is perfected by the martyrs. John says that "all the saints have washed their robes … in the blood of the Lamb." [Rev. 7:14.] Indulgences teach that they wash their robes in the blood of the saints.

3. Authorities against indulgences and merits of martyrs*

To the Palestinians, Leo, Bishop of Rome, writes very clearly against this sacrilege: "Although," he says, " 'Precious in the sight of the Lord was the death of many saints' [Ps. 116:15; cf. Ps. 115:15, Vg.], yet the slaying of no innocent person has been the propitiation of the world. The righteous have received, not given, crowns; and from believers' fortitude have come examples of patience, not gifts of righteousness. Each one surely died his own death, not paying by his end the debt of another, since one Lord Christ exists, in whom all are crucified, all are dead, buried, raised." As this idea was worth remembering, he repeated it in another place.6 Surely, nothing clearer could be desired to puncture this impious dogma. And Augustine, no less appropriately, expresses the same judgment: "Even though we as brethren," he says, "die for our brethren, no martyr's blood is shed for the forgiveness of sins. This Christ has done for us, and he has bestowed this upon us not for us to imitate him, but for us to rejoice." The same idea occurs in another place: "Just as the only Son of God became the Son of Man that he might make us sons of God with him, so on our behalf he alone underwent punishment without deserving ill that we through him, without deserving good, might attain a grace not due us."

aAssuredly, while all their doctrine is patched together out of terrible sacrileges and blasphemies, this is a more astounding blasphemy than the rest. Let them recognize whether or not these are their judgments: that martyrs by their death have given more to God and deserved more than they needed for themselves, and that they had a great surplus of merits to overflow to others. In order, therefore, that this great good should not be superfluous, they mingle their blood with the blood of Christ; and out of the blood of both, the treasury of the church is fabricated for the forgiveness and satisfaction of sins. And Paul's statement, "In my body I complete what is lacking in Christ's afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church" [Col. 1:24], is to be understood in this sense.

What is this but to leave Christ only a name, to make him another common saintlet who can scarcely be distinguished in the throng? He, he alone, deserved to be preached; he alone set forth; he alone named; he alone looked to when there was a question of obtaining forgiveness of sins, expiation, sanctification. But let us listen to their notions. Lest the martyrs' blood be fruitlessly poured out, let it be conferred upon the common good of the church. Is this so? Was it unprofitable for them to glorify God through their death? to attest his truth by their blood? to bear witness by their contempt of the present life that they are seeking a better life? by their constancy, to strengthen the faith of the church but to break the stubbornness of its enemies? But the fact is that they recognize no fruit if Christ alone is the propitiator, if he alone has died for the sake of our sins, if he alone has been offered for our redemption. Peter and Paul, nonetheless, they say, would have received the crown of victory if they had died in their beds. But since they strove even unto death, it would not have squared with God's justice for their sacrifice to go barren and unfruitful. It is as if God did not know how to increase his glory in his servants according to the measure of his gifts. But the church in general receives benefit great enough, when by their triumphs it is kindled with a zeal to fight.

4. Refutation of opposing Scriptural proofs

How maliciously they twist the passage in Paul wherein he says that in his own body he supplies what was lacking in Christ's sufferings [Col. 1:24]! For he refers that lack or that supplement not to the work of redemption, satisfaction, and expiation but to those afflictions with which the members of Christ—namely, all believers—must be exercised so long as they live in this flesh. Therefore, Paul says that of the sufferings of Christ this remains: what once for all he suffered in himself he daily suffers in his members. And Christ distinguishes us by this honor, that he accounts and makes our afflictions his own. Now, when Paul adds "for the church," he does not mean for redemption, for reconciliation, or for satisfaction of the church, but for its upbuilding and advancement. As he says in another place: He endures everything for the sake of the elect, that they may obtain the salvation that is in Christ Jesus [2 Tim. 2:10]. And he wrote to the Corinthians that it was for their comfort and salvation that he endured whatever tribulations he was suffering [2 Cor. 1:6].

He immediately explains himself by adding that he became a minister of the church not for redemption, but "according to the dispensation that had been given to him, to preach the gospel of Christ" [Col. 1:25 p., cf. Rom. 15:19].

But if my opponents require still another interpreter, let them hear Augustine: "The sufferings," he said, "of Christ are in Christ alone, as in the head; in Christ and the church, as in the whole body. Consequently Paul, as one member, says: 'I supply in my body what is lacking in the sufferings of Christ.' If, then, you—whoever you are who hear this—are among Christ's members, whatever you suffer from those who are not members of Christ was lacking in the sufferings of Christ." But he explains elsewhere to what end the sufferings of the apostles, undergone for the church, tended. "Christ is for me the door [cf. John 10:7] unto you, because you are the sheep of Christ, made ready by his blood. Acknowledge your price, which is not paid by me but preached through me." Then he adds, "As he has laid down his life, so also ought we to lay down our lives for our brethren, for the upbuilding of peace and the strengthening of faith." These are Augustine's words. aAway with the notion that Paul thought anything was lacking in Christ's sufferings with regard to the whole fullness of righteousness, salvation, and life; or that he meant to add anything. For Paul clearly and grandly preaches that Christ so bountifully poured out the richness of grace that it far surpassed the whole power of sin [cf. Rom. 5:15]. By this alone, not by the merit of their life or death, have all the saints been saved, as Peter eloquently witnesses [cf. Acts 15:11]. So, then, one who would rest the worthiness of any saint anywhere save in God's mercy would be contemptuous of God and his Anointed. But why do I tarry here any longer, as if this were still something obscure, when to lay bare such monstrous errors is to vanquish them?

5. Indulgences oppose the unity and the comprehensive activity of the grace of Christ

Now—to pass over such abominations—who taught the pope to inclose in lead and parchment the grace of Jesus Christ, which the Lord willed to be distributed by the word of the gospel? Obviously, either the gospel of God or indulgences must be false. bPaul testifies that Christ is offered to us through the gospel, with every abundance of heavenly benefits, with all his merits, all his righteousness, wisdom, and grace, without exception. bHe states that the message of reconciliation was entrusted to ministers to act as ambassadors with Christ, as it were, appealing through them [2 Cor. 5:18–21]. "We beseech you, be reconciled to God. For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God" [2 Cor. 5:20–21]. And believers know the value of the fellowship11 of Christ, which, as the same apostle testifies, is in the gospel offered us to enjoy. On the other hand, indulgences draw from the pope's storehouse some modicum of grace. They attach it to lead, parchment, and a certain place—and tear it away from the Word of God!

lf anyone would ask its origin, this abuse seems to have arisen from the fact that when satisfactions severer than all could bear were formerly enjoined upon the penitents, who felt weighed down beyond all measure by the penance imposed upon them, they sought relaxation from the church. The remission made to such persons was called "indulgence." But when they transferred satisfactions to God and said that they were compensations by which men redeemed themselves from God's judgment, at the same time also they converted those indulgences into expiatory remedies that were to free us from our deserved punishments.12 They have with such great shamelessness fashioned those blasphemies to which we have referred that they can have no excuse.

(Refutation of the doctrine of purgatory by an exposition of the Scriptural passages adduced to support it, 6–10)

6. Refutation of the doctrine of purgatory is necessary

Now let them no longer trouble us with their "purgatory," because with this ax it has already been broken, hewn down, and overturned from its very foundations. And I do not agree with certain persons who think that one ought to dissemble on this point, and make no mention of purgatory, from which, as they say, fierce conflicts arise but little edification can be obtained. Certainly, I myself would advise that such trifles be neglected if they did not have their serious consequences. But, since purgatory is constructed out of many blasphemies and is daily propped up with new ones, and since it incites to many grave offenses, it is certainly not to be winked at. One could for a time perhaps in a way conceal the fact that it was devised apart from God's Word in curious and bold rashness; that men believed in it by some sort of "revelations" forged by Satan's craft; and that some passages of Scripture were ignorantly distorted to confirm it. Still, the Lord does not allow man's effrontery so to break in upon the secret places of his judgments; and he sternly forbade that men, to the neglect of his Word, should inquire after truth from the dead [Deut. 18:11]. Neither does he allow his Word to be so irreligiously corrupted.

Let us, however, grant that all those things could have been tolerated for a time as something of no great importance; but when expiation of sins is sought elsewhere than in the blood of Christ, when satisfaction is transferred elsewhere, silence is very dangerous. Therefore, we must cry out with the shouting not only of our voices but of our throats and lungs that purgatory is a deadly fiction of Satan, which nullifies the cross of Christ, inflicts unbearable contempt upon God's mercy, aand overturns and destroys our faith. For what means this purgatory of theirs but that satisfaction for sins is paid by the souls of the dead after their death? Hence, when the notion of satisfaction is destroyed, purgatory itself is straightway torn up by the very roots. aBut if it is perfectly clear from our preceding discourse that the blood of Christ is the sole satisfaction for the sins of believers, the sole expiation, the sole purgation, what remains but to say that purgatory is simply a dreadful blasphemy against Christ? I pass over the sacrileges by which it is daily defended, the minor offenses that it breeds in religion, and innumerable other things that we see have come forth from such a fountain of impiety.

7. Alleged proofs of purgatory from the Gospels*

But it behooves us to wrest from their hands those passages of Scripture which they falsely and wrongly are accustomed to seize upon.

When the Lord, they say, makes known that the "sin against the Holy Spirit is not to be forgiven either in this age or in the age to come" [Matt. 12:32; Mark 3:28–29; Luke 12:10], he hints at the same time that there is forgiveness of certain sins in the world to come. But who cannot see that the Lord is there speaking of the guilt of sin? But if this is so, what has it to do with their purgatory? Since, in their opinion, punishment of sins is undergone in purgatory, why do they not deny that their guilt is remitted in the present life? But to stop their railing against us, they shall have an even plainer refutation. When the Lord willed to cut off all hope of pardon for such shameful wickedness, he did not consider it enough to say that it would never be forgiven; but in order to emphasize it even more, he used a division by which he embraced the judgment that the conscience of every man experiences in this life and the final judgment that will be given openly at the resurrection. It is as if he said: "Beware of malicious rebellion as of present ruin. For he who would purposely try to extinguish the proffered light of the Spirit will attain pardon neither in this life, which is given to sinners for their conversion, nor in the Last Day, on which the lambs will be separated from the goats by the angels of God and the Kingdom of Heaven will be cleansed of all offenses" [cf. Matt. 25:32–33].

Then they bring forward that parable from Matthew: "Make friends with your adversary … lest sometime he hand you over to the judge, and the judge to the constable, and the constable to the prison … whence you cannot get out until you have paid the last penny" [Matt. 5:25–26 p.]. If in this passage the judge signifies God, the accuser the devil, the guard the angel, the prison purgatory, I shall willingly yield to them. But suppose it be clear to all that Christ, in order to urge his followers more cogently to equity and concord, meant to show the many dangers and evils to which men expose themselves who obstinately prefer to demand the letter of the law16 rather than to act out of equity and goodness. Where, then, I ask, will purgatory be found?

8. From Philippians, Revelation, and Second Maccabees*

They seek proof from Paul's statement wherein he declares that the knees of those in heaven, in earth, and in the nether regions17 bow to Christ [Phil. 2:10]. For they take it to be generally acknowledged that "nether regions" cannot be understood to mean those who have been bound over to eternal damnation; accordingly, it remains to apply the term to souls agonizing in purgatory. They would not be reasoning badly if by the bowing of the knee the apostle designated true and godly worship. But since he is simply teaching that dominion has been given to Christ with which to subject all creatures, what hinders us from understanding by the expression "nether regions" the devils, who will obviously be brought before God's judgment seat and who will recognize their judge with fear and trembling [cf. James 2:19; 2 Cor. 7:15]? So Paul himself elsewhere explains the same prophecy: "We shall all stand before Christ's judgment seat. For it is written: 'As I live … every knee shall bow to me,' " etc. [Rom. 14:10–11, Vg.; Isa. 45:23].

Yet what is said in Revelation must not be interpreted in that way: "I heard every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and in the sea, and all therein, saying: 'To him who sits upon the throne and to the Lamb be blessing and honor and glory and power forever and ever!' " [Rev. 5:13]. That, indeed, I readily concede, but what sorts of creatures do they think are here spoken of? For surely it is quite certain here that both creatures lacking in reason and inanimate ones are comprehended. This merely declares the fact that individual parts of the world, from the very peak of heaven even to the center of the earth, in their own way declare the glory of their Creator [cf. Ps. 19:1].

What they bring forward from the history of the Maccabees [2 Macc. 12:43] I deem unworthy of reply, lest I seem to include that work in the canon of the sacred books. But Augustine, they say, takes it as canonical. First, with what assurance? "The Jews," he says, "do not consider the writing of the Maccabees as the Law, Prophets, and Psalms, to which the Lord attests as to his witnesses, saying: 'Everything written about me in the Law … and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled' [Luke 24:44]. But it is not unprofitably received by the church if it be soberly read or hearkened to." But Jerome teaches without hesitation that its authority is of no value for the proving of doctrine. From that ancient work attributed to Cyprian, On the Exposition of the Creed, it is perfectly clear that this book had no place in the ancient church. And why do I here carry on this vain argument? As if the author himself does not well enough show what deference is due him, when at the end he implores pardon if he has said anything amiss [2 Macc. 15:39]! Surely, he who admits that his writings are in need of pardon does not claim to be the oracle of the Holy Spirit. Besides this, the piety of Judas is praised for no other distinction than that he had a firm hope of the final resurrection when he sent an offering for the dead to Jerusalem [2 Macc. 12:43]. Nor did the writer of that history set down Judas' act to the price of redemption, but regarded it as done in order that they might share in eternal life with the remaining believers who had died for country and religion. This deed was not without superstition and wrongheaded zeal, but utterly foolish are those who extend the sacrifice of the law even down to us, when we know that by the advent of Christ what was then in use ceased.

9. The crucial passage in 1 Cor., ch. 3*

But in Paul they claim to have an invincible phalanx, that cannot be so easily overwhelmed. "If anyone builds on this foundation with gold, silver, precious stones, wood, hay, stubble—each man's work, such as it is, will become manifest; for the Day of the Lord will disclose it, because it will be revealed with fire, and the fire will test what sort of work each one has done.… If any man's work is burned up, he will suffer loss, though he himself will be saved, but only as through fire" [1 Cor. 3:12–13, 15]. What fire, they ask, can this be but that of purgatory, by which the filth of sins is cleansed away that we may enter into the Kingdom of God as pure men? Yet very many of the ancient writers understood this in another way, namely, as tribulation, or the cross, through which the Lord tests his own that they may not linger in the filth of the flesh. And that is much more probable than any fictitious purgatory. Notwithstanding, I do not agree with these men, for it seems to me that I have attained a much surer and clearer understanding of this passage.

Yet before I set it forth, I should like my opponents to answer me whether they think that all the apostles and the saints had to go through this purgatorial fire. They will deny it, I know, for it would be utterly absurd that purgation should be required of those whose merits they imagine to redound beyond measure to all the members of the church. But the apostle declares this, and he does not say that the works of certain ones will be proved, but of all. And this is not my argument but Augustine's, who thus opposes that interpretation. And, what is more absurd, he says not that they shall pass through the fire on account of any works whatsoever, but that if they have built up the church with the highest faithfulness, they will receive a reward when their work has been tested by fire.22

First, we see that the apostle used a metaphor when he called the doctrines devised by men's own brains "wood, hay, and stubble." Besides, the metaphor is readily explained: namely, that just as wood when put on fire is at once consumed and lost, so those things cannot last when the hour comes for them to be tested. Now everyone knows that such a trial proceeds from the Spirit of God. Therefore, to follow the thread of his metaphor and put the parts in their proper relationships to one another, he calls the trial of the Holy Spirit "fire." For the nearer gold and silver are placed to the fire, the more certain proofs do they give of their genuineness and purity. So, too, the more carefully the truth of the Lord is tested in a spiritual examination, the more completely its authority is confirmed. As "hay, wood, and stubble" are set on fire, they are suddenly consumed. Thus the inventions of men, not grounded in the Word of the Lord, cannot bear testing by the Holy Spirit, but immediately fall and perish. In short, if forged doctrines are compared to "wood, hay, and stubble" because like "wood, hay, and stubble" they are burned in the fire and destroyed, it is, however, by the Spirit of the Lord only that they are destroyed and dissipated. It follows that the Spirit is that fire whereby they will be tested, whose test Paul calls "the Day of the Lord" [1 Cor. 3:13, Vg.], according to the common usage of Scripture. For it is called "the Day of the Lord" whenever he reveals his presence to men in any way; then, indeed, does his face most of all shine, when his truth gleams forth. Now we have proved that Paul means by "the fire" nothing else but the testing by the Holy Spirit.

But how are those saved through that fire who suffer the loss of their works? [1 Cor. 3:15.] This will not be difficult to understand if we consider what kind of men he is speaking of. For he is referring to those builders of the church who, keeping a lawful foundation, build upon it with unsuitable materials. That is, those who do not fall away from the principal and necessary doctrines of the faith go astray in less important and less dangerous ones, mingling their own invention with the Word of God. Such persons, I say, must undergo the loss of their work with the annihilation of their inventions. "Yet they are saved, but as through fire." [1 Cor. 3:15.] That is, not that their ignorance and delusion are acceptable to the Lord, but because they are cleansed from these by the grace and power of the Holy Spirit. Accordingly, anyone who fouls the golden purity of God's Word with this filth of purgatory must undergo the loss of his work.

10. The appeal to the early church cannot help the Romanists

But, they say, this was a most ancient observance of the church. Paul answers this objection, while also embracing his own age in his judgment, when he declares that all must undergo loss of their work who in building the church lay any foundation unsuitable to it [1 Cor. 3:11–15].

When my adversaries, therefore, raise against me the objection that prayers for the dead have been a custom for thirteen hundred years, I ask them, in turn, by what word of God, by what revelation, by what example, is this done? Not only are testimonies of Scripture lacking on this point, but all examples of the saints that one may there read of show no such thing. Concerning mourning and the office of burial, one there finds many and sometimes detailed accounts; but concerning such prayers, you can see not one tittle. Yet, the more important the matter is, the more it ought to have been expressly mentioned. And also, those ancient writers who poured out prayers for the dead saw that in this point they lacked both the command of God and lawful example.24 Why, then, did they dare do it? On this ground, I say, that they yielded something to human nature; and for that reason, I contend that what they did ought not to be made an example to imitate. For since believers ought to undertake no task, except with an assured conscience, as Paul teaches [Rom. 14:23], this certainty is especially needed in prayer. Yet it is likely that they were impelled for another reason: namely, they were seeking comfort to relieve their sorrow, and it seemed inhuman to them not to show before God some evidence of their love toward the dead. All men know by experience how man's nature is inclined to this feeling.

There was, also, an accepted custom that, like a brand, set men's minds on fire. We know that among all the Gentiles and in all times rites have been held for the dead, and each year cleansing rites were held for their souls. But even though Satan deluded stupid mortals with these tricks, he took occasion to deceive them from a correct principle: that death is not destruction but a crossing over from this life to another. There is no doubt that this very superstition holds the Gentiles convicted before God's judgment seat because they neglected to give thought to the life to come in which they professed to believe. Now Christians, in order not to be worse than profane men, were ashamed not to devote some rite to the dead, as if they had quite ceased to be. From this arose that ill-advised diligence. For if they had hesitated to attend to funeral rites, banquets, and offerings, they thought they would be exposed to great reproach. But that which derived from perverse emulation was so constantly increased by new additions that to help the dead in distress became the papacy's principal mark of holiness. cBut Scripture supplies another far better and more perfect solace when it testifies: "Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord" [Rev. 14:13]. And it adds the reason: "Henceforth they rest from their labors." Moreover, we ought not to indulge our affection to the extent of setting up a perverse mode of prayer in the church.

Surely, any man endowed with a modicum of wisdom easily recognizes that whatever he reads among the ancient writers concerning this matter was allowed because of public custom and common ignorance. I admit that the fathers themselves were also carried off into error. For heedless credulity commonly deprives men's minds of judgment. And yet, the reading of those authors shows how hesitantly they commended prayers for the dead. Augustine relates in his Confessions that his mother, Monica, emphatically requested that she be remembered in the celebration of rites at the altar. This was obviously an old woman's request, which the son did not test by the norm of Scripture; but he wished to be approved by others for his natural affection. Moreover, the book The Care to Be Taken for the Dead, composed by him, contains so many doubts that by its coldness it ought rightly to extinguish the heat of foolish zeal on the part of anyone who desires to be an intercessor for the dead; with its cold conjectures, to be sure, this treatise will render careless those who previously were careful. Its only support for the practice is that this office of prayers for the dead is not to be despised, for the custom has been prevalent.

But, though I concede to the ancient writers of the church that it seemed a pious act to help the dead, we ought ever to keep the rule that cannot deceive: that it is not lawful to interject anything of our own in our prayers. But our requests ought to be subjected to the Word of God; for it is within his decision to prescribe what he wills to be asked. Now, since the entire law and gospel do not furnish so much as a single syllable of leave to pray for the dead, it is to profane the invocation of God to attempt more than he has bidden us.

But, lest our adversaries boast that the ancient church is, as it were, their partner in error, I say that there is a wide difference. The ancients did it in memory of the dead, lest they should seem to have cast away all concern for them. But at the same time they confessed that they were in doubt regarding the state of the dead. About purgatory they were so noncommittal that they considered it as a thing uncertain. Our present adversaries demand that what they have dreamed up concerning purgatory be held without question as an article of faith. The ancients rarely and only perfunctorily commended their dead to God in the communion of the Sacred Supper. The moderns zealously press the care of the dead, and with importunate preaching cause it to be preferred to all works of love.27

Indeed, it would be not at all difficult for us to bring forth some testimonies of the ancient writers that clearly overthrow all those prayers for the dead then in use. Such a one is the statement of Augustine when he teaches that the resurrection of the flesh and everlasting glory are awaited by all, but that every man when he dies receives the rest that follows death if he is worthy of it. Therefore, he bears witness that all godly men, no less than prophets, apostles, and martyrs, immediately after death enjoy blessed repose. If such is their condition, what, I beg of you, will our prayers confer upon them?

I pass over those grosser superstitions with which they have bewitched the simple-minded; although these are innumerable, and for the most part so monstrous that no color of decency can be given to them. I am also silent upon those utterly base traffickings which, in view of the world's great ignorance, they have in their lust carried on. For there would never be an end; and without an enumeration of them my good readers will have enough to steady their consciences.

----

Source: Calvin's Institutes by John Calvin