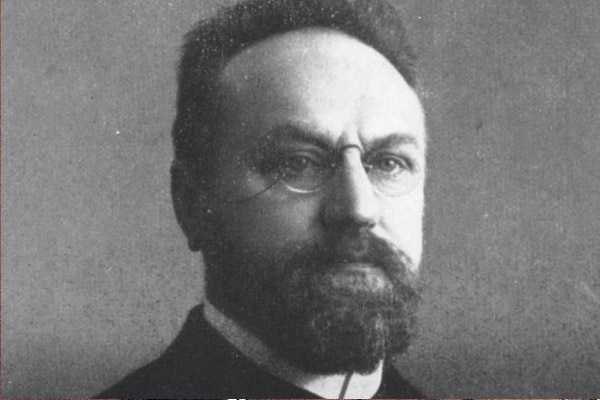

by Herman Bavinck

by Herman Bavinck

Scripture speaks of the perseverance of the saints in the same way it does about sanctification. It admonishes believers to persevere to the end (Matt. 24:13; Rom. 2:7–8); to remain in Christ, in his word, in his love (John 15:1–10; 1 John 2:6, 24, 27; 3:6, 24; 4:12ff.); to continue in the faith, not shifting (Col. 1:23; Heb. 2:1; 3:14; 6:11); to be faithful to death (Rev. 2:10, 26). Sometimes it speaks as if apostasy is a possibility: “If you think you are standing, watch out that you do not fall” (1 Cor. 10:12); it warns against superciliousness and threatens heavy punishment for unfaithfulness (Ezek. 18:24; Matt. 13:20–21; John 15:2; Rom. 11:20, 22; 2 Tim. 2:12; Heb. 4:1; 6:4–8; 10:26–31; 2 Pet. 2:18–22). It even seems to name various persons in whose lives there was a falling away: David in committing adultery, Solomon in his idolatry, Hymenaeus and Alexander (1 Tim. 1:19–20; 2 Tim. 2:17–18), Demas (2 Tim. 4:10), false prophets and teachers who deny the Lord who bought them (2 Pet. 2:1), believers who have fallen away from grace and the faith (Gal. 5:4; 1 Tim. 4:1). On the basis of these texts, Pelagians, Roman Catholics, Socinians, Remonstrants, Mennonites, Quakers, Methodists, and so forth, and even Lutherans have taught the possibility of a complete loss of the grace received.67 Augustine, on the other hand, arrived at the confession of the perseverance of the saints. However, since he deemed uncertainty and fear with respect to salvation beneficial in the life of believers, he held that those who had been born again in baptism could lose the grace they had received, but if they belonged to the number of the predestined, they would in any case receive it back before their death. Hence while believers could totally lose the grace received, the elect could not finally lose it. In the Catholic and later Roman church, many theologians, in earlier and later times, agreed with him; still the Reformed, and the Reformed alone, maintained this doctrine and linked it with the assurance of faith.68

Now the question with respect to this doctrine of perseverance is not whether those who have obtained a true saving faith could not, if left to themselves, lose it again by their own fault and sins; nor whether sometimes all the activity, boldness, and comfort of faith actually ceases, and faith itself goes into hiding under the cares of life and the delights of the world. The question is whether God upholds, continues, and completes the work of grace he has begun, or whether he sometimes permits it to be totally ruined by the power of sin. Perseverance is not an activity of the human person but a gift from God. Augustine saw this very clearly. Only he made a distinction between two kinds of grace and considered possible a grace of regeneration and faith that by itself was amissible and that, for its continued existence, had to be augmented from without by a second grace, the grace of perseverance. That second grace, then, is a superadded gift, has no connection with the first, and has in fact no influence whatever outside the Christian life. Among the Reformed the doctrine of perseverance was very different. It is a gift of God. He watches over it and sees to it that the work of grace is continued and completed. He does not, however, do this apart from believers but through them. In regeneration and faith, he grants a grace that as such bears an inamissible character; he grants a life that is by nature eternal; he bestows the benefits of calling, Justification, and glorification that are mutually and unbreakably interconnected. All of the above-mentioned admonitions and threats that Scripture addresses to believers, therefore, do not prove a thing against the doctrine of perseverance. They are rather the way in which God himself confirms his promise and gift through believers. They are the means by which perseverance in life is realized. After all, perseverance is also not coercive but, as a gift of God, impacts humans in a spiritual manner. It is precisely God’s will, by admonition and warning, morally to lead believers to heavenly blessedness and by the grace of the Holy Spirit to prompt them willingly to persevere in faith and love. It is therefore completely mistaken to reason from the admonitions of Holy Scripture to the possibility of a total loss of grace. This conclusion is as illegitimate as when, in the case of Christ, people infer from his temptation and struggle that he was able to sin. The certainty of the outcome does not render the means superfluous but is inseparably connected with them in the decree of God. Paul knew with certainty that in the case of shipwreck no one would lose one’s life, yet he declares, “Unless these men stay in the ship, you cannot be saved” (Acts 27:22, 31).

As for the examples Scripture is said to cite as instances of real apostasy, it is impossible to prove that all these persons (1) either had truly received the grace of regeneration (Hymeneus, Alexander, Demas, persons referred to in 1 Tim. 4:1; 2 Pet. 2:1); (2) or really lost it in their fall and later received it back again (David, Solomon); (3) or really did receive it but never got it back (Heb. 6:4–8; 10:26–31; 2 Pet. 2:18–22). These last texts seem to present the most formidable obstacle to the confession of the perseverance of the saints. Still this is an illusion. For, also those who hold to the possibility of falling away have to accept that the reference here is to a very particular sin. Even according to themselves, while grace is amissible, it can be regained after total loss. The opinion of Montanists and Novatians, who infer from these passages that the lapsed may never be readmitted to membership in the church, has been universally rejected by Christian churches. When Scripture expressly states that it is impossible to restore to repentance those who are in view in these texts (Heb. 6:4; 10:26; 2 Pet. 2:20; 1 John 5:16), it cannot be denied that the reference is to a sin that carries with it a judgment of hardening and that makes repentance impossible. And of such a sin—also according to the confession of those who hold to the impossibility of a falling away—there is only one, namely, the sin of blasphemy against the Holy Spirit.69 Now if this is true, then the doctrine of the falling away of saints leads to the conclusion that either the sin of blaspheming the Holy Spirit can be committed also, or even perhaps only, by those who are born again,70 or the above-mentioned texts lose all their evidential value against the doctrine of the perseverance of the saints. But this is not all. For those who consider total apostasy a possibility have to make a distinction between the sins by which the grace of regeneration is lost and other sins by which it is not lost. In other words, they are compelled to resort to the Roman Catholic distinction between mortal and venial sins, unless they would hold that that grace is lost by every—even the most minor—sin. But by adopting this view, they would falsify the whole of morality, misconstrue the nature of sin, and introduce an oppressive casuistry that would ensnare the believer’s conscience. Furthermore, on this view one cannot arrive at the assurance of faith, achieve the ability to work in peace, and experience the quiet development and growth of the Christian life. Continuity can be lost at any moment. Hollaz tries to argue that regeneration can be lost three, four, or more times and still be recovered.71 Finally, the doctrine of the possible apostasy of the saints is so far from escaping the difficulties it seeks to avoid that it rather magnifies and increases them. For if in this connection it holds on to the immutability of God’s foreknowledge, then finally only those are saved whom God has eternally known would be, and the human will cannot undo the certainty of this outcome. Or it must proceed to deny predestination and foreknowledge in every sense of these terms, thus making everything uncertain and unstable, including the love of the Father, the grace of the Son, and the communion of the Holy Spirit. God may have manifested his love; Christ may have died for sinners; the Holy Spirit may have implanted rebirth and faith in the heart of people; the believer may be able to say with Paul: “I delight in the law of God in my inmost self” (Rom. 7:22). Yet ultimately, right up until the hour of one’s death—indeed, why not also on the other side of the grave?—the human will remains the decisive and all-controlling power. Everything will be as that will determines it will be.

Scripture, however, teaches a very different doctrine. The Old Testament already clearly states that the covenant of grace does not depend on the obedience of human beings. It does indeed carry with it the obligation to walk in the way of the covenant but that covenant itself rests solely in God’s compassion. If the Israelites nevertheless again and again become unfaithful and adulterous, the prophets do not conclude from this that God changes, that his covenant wavers and that his promises fail. On the contrary: God cannot and may not break his covenant. He has voluntarily—with a solemn oath—bound himself by it to Israel. His fame, his name, and his honor depend on it. He cannot abandon his people. His covenant is an everlasting covenant that cannot waver. He himself will give to his people a new heart and a new spirit, inscribe the law in their inmost self, and cause them to walk in his statutes. And later, when Paul confronts the same fact of Israel’s unfaithfulness, his heart filled with grief, he does not conclude from this that the word of God has failed, but continues to believe that God has compassion on whom he will, that his gifts and calling are irrevocable, and that not all who are descended from Israel belong to Israel (Rom. 9–11).

Similarly, John testifies of those who fell away: they were not of us or else they would have continued with us (1 John 2:19). Whatever apostasy occurs in Christianity, it may never prompt us to question the unchanging faithfulness of God, the certainty of his counsel, the enduring character of his covenant, or the trustworthiness of his promises. One should sooner abandon all creatures than fail to trust his word. And that word in its totality is one immensely rich promise to the heirs of the kingdom. It is not just a handful of texts that teach the perseverance of the saints: the entire gospel sustains and confirms it. The Father has chosen them before the foundation of the world (Eph. 1:4), ordained them to eternal life (Acts 13:48), to be conformed to the image of his Son (Rom. 8:29). This election stands (Rom. 9:11; Heb. 6:17) and in due time carries with it the calling and Justification and glorification (Rom. 8:30). Christ, in whom all the promises of God are Yes and Amen (2 Cor. 1:20), died for those who were given him by the Father (John 17:6, 12) in order that he might give them eternal life and not lose a single one of them (6:40; 17:2); he therefore gives them eternal life and they will never be lost in all eternity; no one will snatch them out of his hand (6:39; 10:28). The Holy Spirit who regenerates them remains eternally with them (14:16) and seals them for the day of redemption (Eph. 1:13; 4:30). The covenant of grace is firm and confirmed with an oath (Heb. 6:16–18; 13:20), unbreakable like a marriage (Eph. 5:31–32), like a testament (Heb. 9:17), and by virtue of that covenant, God calls his elect. He inscribes the law upon their inmost being, puts his fear in their heart (Heb. 8:10; 10:14ff.), will not let them be tempted beyond their strength (1 Cor. 10:13), confirms and completes the good work he has begun in them (1 Cor. 1:9; Phil. 1:6), and keeps them for the return of Christ to receive the heavenly inheritance (1 Thess. 5:23; 2 Thess. 3:3; 1 Pet. 1:4–5). In his intercession before the Father, Christ acts in such a way that their faith may not fail (Luke 22:32), that in the world they may be kept from the evil one (John 17:11, 20), that they may be saved for all times (Heb. 7:20), that their sins will be forgiven them (1 John 2:1), and that they may all be where he is to behold his glory (John 17:24). The benefits of Christ, which the Holy Spirit imparts to them, are all irrevocable (Rom. 11:29). Those who are called are also glorified (8:30). Those who are adopted as children are heirs of eternal life (8:17; Gal. 4:7). Those who believe have eternal life already here and now (John 3:16). That life itself, being eternal, cannot be lost. It cannot die since it cannot sin (1 John 3:9). Faith is a firm ground (Heb. 11:1), hope is an anchor (6:19) and does not disappoint us (Rom. 5:5), and love never ends (1 Cor. 13:8).

------

From Reformed Dogmatics (4 Volume Set) by Herman Bavinck, Volume 4: Holy Spirit, Church and New Creations