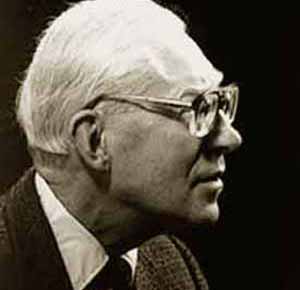

By J. I. Packer

By J. I. Packer

Martin Luther described the doctrine of justification by faith as articulus stantis vel cadentis ecclesiæ—the article of faith that decides whether the church is standing or falling.

By this he meant that when this doctrine is understood, believed, and preached, as it was in New Testament times, the church stands in the grace of God and is alive; but where it is neglected, overlaid, or denied, as it was in mediaeval Catholicism, the church falls from grace and its life drains away, leaving it in a state of darkness and death. The reason why the Reformation happened, and Protestant churches came into being, was that Luther and his fellow Reformers believed that Papal Rome had apostatised from the gospel so completely in this respect that no faithful Christian could with a good conscience continue within her ranks.

Justification by faith has traditionally, and rightly, been regarded as one of the two basic and controlling principles of Reformation theology. The authority of Scripture was the formal principle of that theology, determining its method and providing its touchstone of truth; justification by faith was its material principle, determining its substance. In fact, these two principles belong inseparably together, for no theology that seeks simply to follow the Bible can help concerning itself with what is demonstrably the essence of the biblical message. The fullest statement of the gospel that the Bible contains is found in the epistle to the Romans, and Romans minus justification by faith would be like Hamlet without the Prince.

A further fact to weigh is that justification by faith has been the central theme of the preaching in every movement of revival and religious awakening within Protestantism from the Reformation to the present day. The essential thing that happens in every true revival is that the Holy Spirit teaches the church afresh the reality of justification by faith, both as a truth and as a living experience. This could be demonstrated historically from the records of revivals that we have; and it would be theologically correct to define revival simply as God the Spirit doing this work in a situation where previously the church had lapsed, if not from the formal profession of justification by faith, at least from any living apprehension of it.

This being so, it is a fact of ominous significance that Buchanan’s classic volume [THE DOCTRINE OF JUSTIFICATION}, now a century old, is the most recent full-scale study of justification by faith that English speaking Protestantism (to look no further) has produced. If we may judge by the size of its literary output, there has never been an age of such feverish theological activity as the past hundred years; yet amid all its multifarious theological concerns it did not produce a single book of any size on the doctrine of justification. If all we knew of the church during the past century was that it had neglected the subject of justification in this way, we should already be in a position to conclude that this has been a century of religious apostasy and decline. It is worth our while to try and see what has caused this neglect, and what are the effects of it within Protestant communities today; and then we may discern what has to be done for our situation to be remedied.

The doctrine of justification by faith is like Atlas: it bears a world on its shoulders, the entire evangelical knowledge of saving grace. The doctrines of election, of effectual calling, regeneration, and repentance, of adoption, of prayer, of the church, the ministry, and the sacraments, have all to be interpreted and understood in the light of justification by faith. Thus, the Bible teaches that God elected men in eternity in order that in due time they might be justified through faith in Christ. He renews their hearts under the Word, and draws them to Christ by effectual calling, in order that he might justify them upon their believing. Their adoption as God’s sons is consequent on their justification; indeed, it is no more than the positive aspect of God’s justifying sentence. Their practice of prayer, of daily repentance, and of good works—their whole life of faith—springs from the knowledge of God’s justifying grace. The church is to be thought of as the congregation of the faithful, the fellowship of justified sinners, and the preaching of the Word and ministry of the sacraments are to be understood as means of grace only in the sense that they are means through which God works the birth and growth of justifying faith. A right view of these things is not possible without a right understanding of justification; so that, when justification falls, all true knowledge of the grace of God in human life falls with it, and then, as Luther said, the church itself falls. A society like the Church of Rome, which is committed by its official creed to pervert the doctrine of justification, has sentenced itself to a, distorted understanding of salvation at every point. Nor can these distortions ever be corrected till the Roman doctrine of justification is put right. And something similar happens when Protestants let the thought of justification drop out of their minds: the true knowledge of salvation drops out with it, and cannot be restored till the truth of justification is back in its proper place. When Atlas falls, everything that rested on his shoulders comes crashing down too.

How has it happened, then, we ask, that so vital a doctrine has come to be neglected in the way that it is today?

The answer is not far to seek. Just as Atlas, with his mighty load to carry, could not hover in mid-air, but needed firm ground to stand on, so does the doctrine of justification by faith. It rests on certain basic presuppositions, and cannot continue without them. Just as the church cannot stand without the gospel of justification, so that gospel cannot stand where its presuppositions are not granted. They are three:

1. The divine authority of Holy Scripture,

2. The divine wrath against human sin, and

3. The substitutionary satisfaction of Christ.

The church loses its grip on these truths, loses its grip on the doctrine of justification, and to that extent on the gospel itself. And this is what has largely happened in Protestantism today.

Let us look at this in detail. Take the three doctrines in order.

1. The divine authority of the Bible.

To Reformation theologians—among whom we count the Puritans, the early Evangelicals, and theologians like Buchanan—what Scripture said, God said. To them, all Scripture had the character claimed for itself by biblical prophecy—the character, that is, of being the utterance of God spoken through human lips. The voice that spoke was human, but the words spoken were divine. So with the Bible: the pen and style were man’s, but the words written were God’s. The Scriptures were both man’s word and God’s word; not just man bearing witness to God, but God bearing witness to Himself. Accordingly, theologians of the Reformation type took the biblical doctrine of sin and salvation exactly as it stood. They traced out the thoughts of Paul, and John, and Peter, and the rest of those who expounded it, with loving care, knowing that hereby they were thinking God’s thoughts after Him. So that, when they found the Bible teaching that God’s relationship with man is regulated by His law, and only those whom His law does not condemn can enjoy fellowship with Him, they believed it. And when they found that the heart of the New Testament gospel is the doctrine of justification and forgiveness of sins, which shows sinners the way to get right with God’s law, they made this gospel the heart of their own message.

But modern Protestants have ceased to do this, because they have jettisoned the historic understanding of the inspiration and authority of Holy Scripture. It has become usual to analyse inspiration naturalistically, reducing it to mere religious insight. Modern theology balks at equating the words of the Bible with the words of God, and fight shy of asserting that, because these words are inspired, they are therefore inerrant and divinely authoritative. Scripture is allowed a relative authority, based on the supposition that its authors, being men of insight, probably say much that is right; but this is in effect to deny to Scripture the authority which properly belongs to the words of a God who cannot lie. This modern view expressly allows for the possibility that sometimes the biblical writers, being children of their age, had their minds so narrowed by conditioning factors in their environment that, albeit unwittingly, they twisted and misstated God’s truth. And when any particular biblical idea cuts across what men today like to think, modern Protestants are fatally prone to conclude that this is a case in point, where the Bible saw things crooked, but we today, differently conditioned, can see them straight.

So here. Modern man, like many pre-Christian pagans, likes to think of himself as a son of God by creation, born into the divine family and an object of God’s endless paternal care. The thought appeals, for it is both flattering and comforting; it seems to give us a claim on God’s love straight away. Protestants of today (whose habit it is to take pride in being modern) are accordingly disinclined to take seriously the uniform biblical insistence that God’s dealing with man are regulated by law, and that God’s universal relation to mankind is not that of Father, but of Lawgiver and Judge. They grant that this thought meant much to Paul, because of his rabbinic conditioning, and to the Reformers, because legal concepts so dominated the Renaissance culture of their day; but, these Protestants say, forensic imagery is really quite out of place for expressing the nature of the personal, paternal relationship which binds God to His human creatures. The law-court is a poor metaphor for the Father’s house. Paul was not at his best when talking about justification. We, in our advanced state of enlightenment, can now see that God’s dealings with His creatures are not, strictly speaking, legal at all. Thus modern Protestantism really denies the validity of all the forensic terms in which the Bible explains to us our relationship with God.

The modern Protestant, therefore, is willing to see man as a wandering child, a lost prodigal needing to find a way home to his heavenly Father, but, generally speaking, he is not willing to see him as a guilty criminal arraigned before the Judge of all the earth. The Bible doctrine of justification, however, is the answer to the question of the convicted lawbreaker: how can I get right with God’s law? How can I be just with God? Those who refuse to see their situation in these terms will not, therefore, take much interest in the doctrine. Nobody can raise much interest in the answer to a question which, so far as he is concerned, never arises. Thus modern Protestantism, by its refusal to think of man’s relationship with God in the basic biblical terms, has knocked away the foundation of the gospel of justification, making it seem simply irrelevant to man’s basic need.

The second doctrine which the gospel of justification presupposes is:

2. The divine wrath against human sin.

Just as modern Protestants are reluctant to believe that man has to deal with God, not as a Father, but as a Judge, so they are commonly unwilling to believe that there is in God a holy antipathy against sin, a righteous hatred of evil, which prompts Him to exact just retribution when His law is broken. They are not, therefore, prepared to take seriously the biblical witness that man in sin stands under the wrath of God. Some dismiss the wrath of God as another of Paul’s lapses; others reduce it to an impersonal principle of evil coming home (sometimes) to roost: few will allow that wrath is God’s personal reaction to sin, so that by sinning a man makes God his enemy. But Reformation theologians have always believed this; first, because the Bible teaches it, and, second, because they have felt something of the wrath of God in their own convicted and defiled consciences. And they have preached it; and thus they have in past days laid the foundation for proclaiming justification. But where there is an unwillingness to allow that sinners stand under the judicial wrath of God, there is no foundation for the preaching of deliverance from that wrath which is what the gospel of justification is about. Thus in a second way modern Protestantism undercuts that gospel, and robs it of relevance for man’s relationship with God.

The third presupposition is:

3. The substitutionary satisfaction of Christ.

It is no accident that at the time of the Reformation the penal and substitutionary character of the death of Christ, and the doctrine of justification by faith, came to be appreciated together. For in the Bible they belong together. Justification is grounded on the sin-bearing work of the Lamb of God. It is the second, completing stage in the great double transaction whereby Christ was made sin and believing sinners are made ‘the righteousness of God in him’ (2 Corinthians 5:211). Salvation in the Bible is by substitution and exchange: the imputing of men’s sins to Christ, and the imputing of Christ’s righteousness to sinners. By this means, the law, and the God whose law it is, are satisfied, and the guilty are justly declared immune from punishment. Justice is done, and mercy is made triumphant in the doing of it. The imputing of righteousness to sinners in justification, and the imputing of their sins to Christ on Calvary, thus belong together; and if, in the manner of so much modern Protestantism, the penal interpretation of the Cross is rejected, then there is no ground on which the imputing of righteousness can rest. And a groundless imputation of righteousness to sinners would be a mere legal fiction, an arbitrary pretense on God’s part, an overturning of the moral order of the universe, and a violation of the law which expresses His own holy nature—in short, would be a flat impossibility, which it would be blasphemous even to contemplate. No; if the penal character of Christ’s death be denied, the right conclusion to draw is that God has never justified any sinner, nor ever will. Thus modern Protestantism, by rejecting penal substitution, is guilty of undermining the gospel of justification by faith in yet a third way. For justification cannot be preached in a way that is even reverent when that which alone makes moral sense of it is denied. No wonder, therefore, that the subject of, justification is so widely neglected at the present time.

What must we do to reinstate it in our pulpits and our churches? We must preach it in its biblical setting; we must re-establish its presuppositions. We must reaffirm the authority of Scripture, as truth from the mouth of God. We must reaffirm the inflexible righteousness of God as a Judge, and the terrible reality of His wrath against sin, as Scripture depicts these things. And we must set forth against this black background the great exchange between Christ and His members, the saving transaction which justification completes. The good news of Christ in our place, and we in His, is still God’s word to the world; it is through the foolishness (as men call it) of this message, and this message alone, that God is pleased to save them that believe.

-----

Taken from the Preface of: “THE DOCTRINE OF JUSTIFICATION, An Outline of its History in the Church and of its Exposition from Scripture,” by JAMES BUCHANAN, D.D., LL.D.