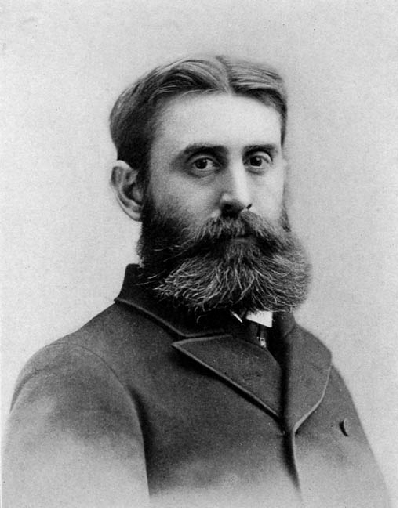

by B. B. Warfield

by B. B. Warfield

The terms "renew," "renewing," are not of frequent occurrence in our English Bible. In the New Testament they do not occur at all in the Gospels, but only in the Epistles (Paul and Hebrews), where they stand, respectively, for the Greek terms ἀνακαινόω (2 Cor. 4:16, Col. 3:10) with its cognates, ἀνακαινίζω (Heb. 6:6) and ἀνανεόομαι (Eph. 4:23), and ἀνακαίνωσις (Rom. 12:2, Tit. 3:5). If we leave to one side 2 Cor. 4:16 and Heb. 6:6, which are of somewhat doubtful interpretation, it becomes at once evident that a definite theological conception is embodied in these terms. This conception is that salvation in Christ involves a radical and complete transformation wrought in the soul (Rom. 12:2, Eph. 4:23) by God the Holy Spirit (Tit. 3:5, Eph. 4:24), by virtue of which we become "new men" (Eph. 4:24, Col. 3:10), no longer conformed to this world (Rom. 12:2, Eph. 4:22, Col. 3:9), but in knowledge and holiness of the truth created after the image of God (Eph. 4:24, Col. 3:10, Rom. 12:2). The conception, it will be seen, is a wide one, inclusive of all that is comprehended in what we now technically speak of as regeneration, renovation and sanctification. It embraces, in fact, the entire subjective side of salvation, which it represents as a work of God, issuing in a wholly new creation (2 Cor. 5:17, Gal. 6:15, Eph. 2:10). What is indicated is, therefore, the need of such a subjective salvation by sinful man, and the provision for this need made in Christ (Eph. 4:20, Col. 3:11, Tit. 3:6).

The absence of the terms in question from the Gospels does not in the least argue the absence from the teaching of the Gospels of the thing expressed by them. This thing is so of the essence of the religion of revelation that it could not be absent from any stage of its proclamation. That it should be absent would require that sin should be conceived to have wrought no subjective injury to man, so that he would need for his recovery from sin only an objective cancelling of his guilt and reinstatement in the favor of God. This is certainly not the conception of the Scriptures in any of their parts. It is uniformly taught in Scripture that by his sin man has not merely incurred the divine condemnation but also corrupted his own heart; that sin, in other words, is not merely guilt but depravity: and that there is needed for man's recovery from sin, therefore, not merely atonement but renewal; that salvation, that is to say, consists not merely in pardon but in purification. Great as is the stress laid in the Scriptures on the forgiveness of sins as the root of salvation, no less stress is laid throughout the Scriptures on the cleansing of the heart as the fruit of salvation. Nowhere is the sinner permitted to rest satisfied with pardon as the end of salvation; everywhere he is made poignantly to feel that salvation is realized only in a clean heart and a right spirit.

In the Old Testament, for example, sin is not set forth in its origin as a purely objective act with no subjective effects, or in its manifestation as a series of purely objective acts out of all relation to the subjective condition. On the contrary, the sin of our first parents is represented as no less corrupting than inculpating; shame is as immediate a fruit of it as fear (Gen. 3:7). And, on the principle that no clean thing can come out of what is unclean (Job 14:4), all that are born of woman are declared "abominable and corrupt," to whose nature iniquity alone is attractive (Job 15:14–16). Accordingly, to become sinful, men do not wait until the age of accountable action arrives. Rather, they are apostate from the womb, and as soon as they are born go astray, speaking lies (Ps. 58:3): they are even shapen in iniquity and conceived in sin (Ps. 51:5). The propensity (יֵעֶר) of their heart is evil from their youth (Gen. 8:21), and it is out of the heart that all the issues of life proceed (Prov. 4:23, 20:11). Acts of sin are therefore but the expression of the natural heart, which is deceitful above all things and desperately sick (Jer. 17:9). The only hope of an amendment of the life, lies accordingly in a change of heart; and this change of heart is the desire of God for His people (Deut. 5:29) and the passionate longing of the saints for themselves (Ps. 51:10). It is, indeed, wholly beyond man's own power to achieve it. As well might the Ethiopian hope to change his skin and the leopard his spots as he who is wonted to evil to correct his ways (Jer. 13:23); and when it is a matter of cleansing not of hands but of heart—who can declare that he has made his heart clean and is pure from sin (Prov. 20:9)? Men may be exhorted to circumcise their hearts (Deut. 10:16, Jer. 4:4), and to make themselves new hearts and new spirits (Ezek. 18:31); but the background of such appeals is rather the promise of God than the ability of man (Deut. 5:29, Ezek. 11:19, cf. Keil in loc.). It is God alone who can "turn" a man "a new heart" (1 Sam. 10:9), and the cry of the saint who has come to understand what his sin means, and therefore what cleansing from it involves, is ever, "Create (בָּרָא) in me a new heart, O God, and renew (חָדַשׁ) a steadfast spirit within me" (Ps. 51:10 [12]). The express warrant for so great a prayer is afforded by the promise of God who, knowing the incapacity of the flesh, has Himself engaged to perfect His people. He will circumcise their hearts, that they may love the Lord their God with all their heart and with all their soul; and so may live (Deut. 30:6). He will give them a heart to know Him that He is the Lord; that so they may really be His people and He their God (Jer. 24:7). He will put His law in their inward parts and write it in their heart so that all shall know Him (Jer. 31:33, cf. 32:39). He will take the stony heart out of their flesh and give them a heart of flesh, that they may walk in His statutes and keep his ordinances and do them, and so be His people and He their God (Ezek. 11:19). He will give them a new heart and take away the stony heart out of their flesh; and put His Spirit within them and cause them to walk in His statutes and keep His judgments and do them: that so they may be His people and He their God (Ezek. 36:26, cf. 37:14). Thus the expectation of a new heart was made a substantial part of the Messianic promise, in which was embodied the whole hope of Israel.

It does not seem open to doubt that in these great declarations we have the proclamation of man's need of "renewal" and of the divine provision for it as an essential element in salvation. We must not be misled by the emphasis placed in the Old Testament on the forgiveness of sins as the constitutive fact of salvation, into explaining away all allusions to the cleansing of the heart as but figurative expressions for pardon. Pardon is no doubt frequently set forth under the figure or symbol of washing or cleansing: but expressions such as those which have been adduced go beyond this. When, then, it is suggested3 that Psalm 51, for example, "contains only a single prayer, namely, that for forgiveness"; and that "the cry, 'Create in me a clean heart' is not a prayer for what we call renewal" but only for "forgiving grace," we cannot help thinking the contention an extravagance,—an extravagance, moreover, out of keeping with its author's language elsewhere, and indeed in this very context where he speaks quite simply of the pollution as well as the guilt of sin as included in the scope of the confession made in this psalm. The word "create" is a strong one and appears to invoke from God the exertion of His almighty power for the production of a new subjective state of things: and it does not seem easy to confine the word "heart" to the signification "conscience" as if the prayer were merely that the conscience might be relieved from its sense of guilt. Moreover, the parallel clause, "Renew a steadfast spirit within me," does not readily lend itself to the purely objective interpretation. That the transformation of the heart promised in the great prophetic passages must also mean more than the production of a clear conscience, is equally undeniable and indeed is not denied. When Jeremiah (31:31–33), for example, represents God as declaring that what shall characterize the New Covenant which He will make with the House of Israel, is that He will put His law in the inward parts of His people and write it in their hearts, he surely means to say that God promises to work a subjective effect in the hearts of Israel, by virtue of which their very instincts and most intimate impulses shall be on the side of the law, obedience to which shall therefore be but the spontaneous expression of their own natures.

It is equally important to guard against lowering the conception of the Divine holiness in the Old Testament until the demand of God that His people shall be holy as He is holy, and the provisions of His Grace to make them holy by an inner creative act, are robbed of more or less of their deeper ethical meaning. Here, too, some recent writers are at fault, speaking at times almost as if holiness in God were merely a sort of fastidiousness, over against which is set not so much all sin as uncleanness, as all uncleanness, as in this sense sin.8 The idea is that what this somewhat squeamish God did not find agreeable those who served Him would discover it well to avoid; rather than that all sin is necessarily abominable to the holy God and He will not abide it in His servants. This lowered view is sometimes even pushed to the extreme of suggesting that "it is nowhere intimated that there is any danger to the sinner because of his uncleanness;" if he is "cut off" that is solely on account of his disobedience in not cleansing himself, not on account of the uncleanness itself. The extremity of this contention is its sufficient refutation. When the sage declares that no one can say "I have made my heart clean, I am pure from sin" (Prov. 20:9), he clearly means to intimate that an unclean heart is itself sinful. The Psalmist in bewailing his inborn sinfulness and expressing his longing for truth in the inward parts and wisdom in the hidden parts, certainly conceived his unclean heart as properly sinful in the sight of God (Ps. 51). The prophet abject before the holy God (Isa. 6) beyond question looked upon his uncleanness as itself iniquity requiring to be taken away by expiatory purging. It would seem unquestionable that throughout the Old Testament the uncleanness which is offensive to Jehovah is sin considered as pollution, and that salvation from sin involves therefore a process of purification as well as expiation.

The agent by whom the cleansing of the heart is effected is in the Old Testament uniformly represented as God Himself, or, rarely, more specifically as the Spirit of God, which is the Old Testament name for God in His effective activity. It has, indeed, been denied that the Spirit of God is ever regarded in the Old Testament as the worker of holiness. But this extreme position cannot be maintained.11 It is true enough that the Spirit of God comes before us in the Old Testament chiefly as the Theocratic Spirit endowing men as servants of the Kingdom, and after that as the Cosmical Spirit, the principle of all world-processes; and only occasionally as the creator of new ethical life in the individual soul. But it can scarcely be doubted that in Ps. 51:11 [13] God's Holy Spirit, or the Spirit of God's holiness, is conceived in that precise manner, and the same is true of Psalm 143:10 (cf. Isa. 63:10, 11 and see Gen. 6:3, Neh. 9:20, 1 Sam. 10:6, 9). It is chiefly, however, in promises of the future that this aspect of the Spirit's work is dwelt upon.14 The recreative activity of the Spirit of God is even made the crowning Messianic blessing (Isa. 32:15, 34:16, 44:3, on the latter of which see Giesebrecht, "Die Berufsbegabung," etc., p. 144, 59:21, Ezek. 11:19, 18:31, 36:27, 37:14, 39:29, Zech. 12:10); and this is as much as to say that the promised Messianic salvation included in it provision for the renewal of men's hearts as well as for the expiation of their guilt.

It would be distinctly a retrogression from the Old Testament standpoint, therefore, if our Lord—Himself, in accordance with Old Testament prophecy (e.g., Isa. 11:1, 42:1, 61:1), endowed with the Spirit (Mt. 3:16, 4:1, 12:18, 28, Mk. 1:10, 12, Lk. 3:22, 4:1, 14, 18, 10:21, Jno. 1:32, 33) above measure (Jno. 3:34)—had neglected the Messianic promise of spiritual renewal. In point of fact, He began His ministry as the dispenser of the Spirit (Mt. 3:11, Mk. 1:8, Lk. 3:16, Jno. 1:33). And the purpose for which He dispensed the Spirit is unmistakably represented as the cleansing of the heart. The distinction of Jesus is, indeed, made to lie precisely in this,—that whereas John could baptise only with water, Jesus baptised with the Holy Spirit: the repentance which was symbolized by the one was wrought by the other. And this repentance (μετάνοια) was no mere vain regret for an ill-spent past (μεταμέλεια), or surface modification of conduct, but a radical transformation of the mind which issues indeed in "fruits worthy of repentance" (Lk. 3:8) but itself consists in an inward reversal of mental attitude.

There is little subsequent reference in the Synoptic Gospels, to be sure, to the Holy Spirit as the renovator of hearts. It is made clear, indeed, that He is the best of gifts and that the Father will not withhold Him from those that ask Him (Lk. 11:13), and that He abides in the followers of Jesus and works in and through them (Mt. 10:20, Mk. 13:11, Lk. 12:12); and it is made equally clear that He is the very principle of holiness, so that to confuse His activity with that of unclean spirits argues absolute perversion (Mt. 12:31, Mk. 3:29, Lk. 12:10). But these two things do not happen to be brought together in these Gospels.

In the Gospel of John, on the other hand, the testimony of the Baptist is followed up by the record of the searching conversation of our Lord with Nicodemus, in which Nicodemus is rebuked for not knowing—though "the teacher of Israel"—that the Kingdom of God is not for the children of the flesh but only for the children of the Spirit (cf. Mt. 3:9). Nicodemus had come to our Lord as to a teacher, widely recognized as having a mission from God. Jesus repels this approach as falling far below recognizing Him for what He really was and for what he had really come to do. As a divinely sent teacher He solemnly assures Nicodemus that something much more effective than teaching is needed: "Verily, verily, I say unto thee, except a man be born a new he cannot see the Kingdom of God" (3:3). And then, when Nicodemus, oppressed by the sense of the profundity of the change which must indeed be wrought in man if he is to be fitted for the Kingdom of God, despairingly inquires "How can this be?" our Lord explains equally solemnly that it is only by a sovereign, recreating work of the Holy Spirit, that so great an effect can be wrought: "Verily, verily, I say unto thee, except a man be born of water and the Spirit he cannot enter into the Kingdom of God" (3:5). Nor, he adds, ought such a declaration to cause surprise: what is born of the flesh can be nothing but flesh; only what is born of the Spirit is spirit. He closes the discussion with a reference to the sovereignty of the action of the Spirit in regenerating men: as with the wind which blows where it lists, we know nothing of the Spirit's coming except Lo, it is here! (3:8). About the phrase, "Born of water and the Spirit" much debate has been had; and various explanations of it have been offered. The one thing which seems certain is that there can be no reference to an external act, performed by men, of their own will: for in that case the product would not be spirit but flesh, neither would it come without observation. Is it fanciful to see here a reference back to the Baptist's, "I indeed baptise with water; He baptises with the Holy Spirit"? The meaning then would be that entrance into the Kingdom of God requires, if we cannot quite say not only repentance but also regeneration, yet at least we may say both repentance and regeneration. In any event it is very pungently taught here that the precondition of entrance into the Kingdom of God is a radical transformation wrought by the Spirit of God Himself.

Beyond this fundamental passage there is little said in John's Gospel of the renovating activities of the Spirit. The communication of the Spirit of 20:22 seems to be an official endowment; and although in 7:39 the allusion appears to be to the gift of the Spirit to believers at large, the stress seems to fall rather on the blessing they bring to others by virtue of this endowment, than on that they receive themselves. There remains only the great promise of the Paraclete. It would probably be impossible to attribute more depth or breadth of meaning than rightfully belongs to them, to the passages which embody this promise (14:16, 26, 15:26, 16:7, 13). But the emphasis appears to be laid in them upon the illuminating (cf. also Lk. 1:15, 41, 67, 2:25, 26; Mt. 22:43) more than upon the sanctifying influences of the Spirit, although assuredly the latter are not wholly absent (16:7–11).

Elsewhere in John, although apart from any specific reference to the Spirit as the agent, repeated expression is given to the fundamental conception of renewal. Men lie dead in their sins and require to be raised from the dead if they are to live (11:25, 26); it is the prerogative of the Son to quicken whom He will (5:21); it is impossible for men to come to the Son, unless they be drawn by the Father (6:44); being in the Son it is only of the Father that they can bear fruit (15:1). Similarly in the Synoptics there is lacking nothing to this teaching, except the specific reference of the effects to the Holy Spirit. What is required of men is nothing less than perfection even as the heavenly Father is perfect (Mt. 5:48—the New Testament form of the Old Testament "Ye shall be holy for I am holy, Jehovah your God," Lev. 19:2). And this perfection is not a matter of external conduct but of internal disposition. One of the objects of the "Sermon on the Mount" is to deepen the conception of righteousness and to carry back both sin and righteousness into the heart itself (Mt. 5:20). Accordingly, the external righteousness of the Scribes and Pharisees is pronounced just no righteousness at all; it is the cleansing merely of the outside of the cup and of the platter (Mt. 23:25), and they are therefore but as whited sepulchres, which outwardly appear beautiful but inwardly are full of dead men's bones (Mt. 23:27, 28). True cleansing must begin from within; and this inward cleansing will cleanse the outside also (Mt. 23:26, 15:11). The fundamental principle is that every tree brings forth fruit according to its nature, whether good or bad; and therefore the tree must be made good and its fruit good, or else the tree corrupt and its fruit corrupt (Mt. 7:17, 12:33, 15:11, Mk. 7:15, Lk. 6:43, 11:34). So invariable and all-inclusive is this principle in its working, that it applies even to the idle words which men speak, by which they may therefore be justly judged: none that are evil can speak good things, "for it is out of the abundance of the heart that the mouth speaketh" (Mt. 12:34). Half-measures are therefore unavailing (Mt. 6:21); a radical change alone will suffice—no mere patching of the new on the old, no pouring of new wine into old bottles (Mt. 9:16, 17, Mk. 2:21, 22, Lk. 5:36, 39). He who has not a wedding-garment—the gift of the host—even though he be called shall not be chosen (Mt. 22:11, 12).

Accordingly when—in the Synoptic parallel to the conversation with Nicodemus—the rich young ruler came to Jesus with his heart set on purchase (as a rich man's heart is apt to be set), pleading his morality, Jesus repelled him and took occasion to pronounce upon not the difficulty only but the impossibility of entrance into the Kingdom of heaven on such terms (Mt. 19:23, Mk. 10:23, Lk. 18:24). The possibility of salvation, He explains, just because it involves something far deeper than this, rests in the hands of God alone (Mt. 19:26, Mk. 10:27, Lk. 18:27). Man himself brings nothing to it; the Kingdom is received in naked helplessness (Mt. 19:21 ||). It is not without significance that, in all the Synoptics, the conversation with the rich young ruler is made to follow immediately upon the incident of the blessing of the little children (Mt. 19:13 ||). When our Lord says, with reference to these children (they were mere babies, Lk. 18:15), that, "Of such is the kingdom of heaven," he means just to say that the kingdom of heaven is never purchased by any quality whatever, to say nothing now of deed: whosoever enters it enters it as a child enters the world,—he is born into it by the power of God. In these two incidents, of the child set in the midst and of the rich young ruler, we have, in effect, acted parables of the new birth; they exhibit to us how men enter the kingdom and set the declaration made to Nicodemus (Jno. 3:1 sq.) before us in vivid object-lesson. And if the kingdom can be entered thus only in nakedness as a child comes into the world, all stand before it in like case and it can come only to those selected therefor by God Himself: where none have a claim upon it the law of its bestowment can only be the Divine will (Mt. 11:27, 20:15).

The broad treatment characteristic of the Gospels only partly gives way as we pass to the Epistles. Discriminations of aspects and stages, however, begin to become evident; and with the increased material before us we easily perceive lines of demarcation which perhaps we should not have noted with the Gospels only in view. In particular we observe two groups of terms standing over against one another, describing, respectively, from the manward and from the Godward side, the great change experienced by him who is translated from the power of darkness into the kingdom of the Son of God's love (Col. 1:13). And within the limits of each of these groups, we observe also certain distinctions in the usage of the several terms which make it up. In the one group are such terms as μετανοεῖν with its substantive μετάνοια, and its cognate μεταμέλεσθαι, and ἐπιστρέφειν and its substantive ἐπιστροφή. These tell us what part man takes in the change. The other group includes such terms as γεννηθῆναι ἄνωθεν or ἐκ τοῦ θεοῦ or ἐκ τοῦ πνεύματος, παλινγενεσία, ἀναγεννᾶν, ἀποκυεῖσθαι, ανανεοῦσθαι, ἀνακαινοῦσθαι, ἀνακαίνωσις. These tell what part God takes in the change. Man repents, makes amendment, and turns to God. But it is by God that men are renewed, brought forth, born again into newness of life. The transformation which to human vision manifests itself as a change of life (ἐπιστροφή) resting upon a radical change of mind (μετάνοια), to Him who searches the heart and understands all the movements of the human soul is known to be a creation (κτίζειν) of God, beginning in a new birth from the Spirit (γεννηθῆναι ἄνωθεν ἐκ τοῦ πνεύματος) and issuing in a new divine product (ποίημα), created in Christ Jesus, into good works prepared by God beforehand that they may be walked in (Eph. 2:10).

There is certainly synergism here; but it is a synergism of such character that not only is the initiative taken by God (for "all things are of God," 2 Cor. 5:18, cf. Heb. 6:6), but the Divine action is in the exceeding greatness of God's power, according to the working of the strength of His might which He wrought in Christ when He raised Him from the dead (Eph. 1:19). The "new man" which is the result of this change is therefore one who can be described no otherwise than as "created" (κτισθέντα) in righteousness and holiness of truth (Eph. 4:24), after the image of God significantly described as "He who created him" (τοῦ κτίσαντος αὐτόν, Col. 3:10),—that is not He who made him a man, but He who has made him by an equally creative efflux of power this new man which he has become. The exhortation that we shall "put on" this new man (Eph. 4:24, cf. 3:9, 10), therefore does not imply that either the initiation or the completion of the process by which the "new creation" (καινὴ κτίσις; 2 Cor. 5:17, Gal. 6:15) is wrought lies in our own power; but only urges us to that diligent coöperation with God in the work of our salvation, to which He calls us in all departments of life (1 Cor. 3:9), and the classical expression of which in this particular department is found in the great exhortation of Phil. 2:12, 13 where we are encouraged to work out our own salvation thoroughly to the end, with fear and trembling, on the express ground that it is God who works in us both the willing and doing for His good pleasure. The express inclusion of "renewal" in the exhortation (Eph. 4:23 ἀνανεοῦσθαι; Rom. 12. μεταμορφοῦσθε τῇ ἀνακαινώσει) is indication enough that this "renewal" is a process wide enough to include in itself the whole synergistic "working out" of salvation (κατεργάζεσθε, Phil. 2:12). But it has no tendency to throw doubt upon the underlying fact that this "working out" is both set in motion (τὸ θέλειν) and given effect (τὸ ἐνεργεῖν), only by the energizing of God (ὅ ἐνεργῶν ἐν ὑμῖν), so that all (τὰ πάντα) is from God (ἐκ τοῦ θεοῦ, 2 Cor. 5:18). Its effect is merely to bring "renewal" (ἀνακαίνωσις) into close parallelism with "repentance" (μετάνοια)—which itself is a gift of God (2 Tim. 2:25, cf. Acts 5:31, 11:18) as well as a work of man—as two names for the same great transaction, viewed now from the Divine, and now from the human point of sight.

It will not be without interest to observe the development of μετανοεῖν, μετάνοια into the technical term to denote the great change by which man passes from death in sin into life in Christ. Among the heathen writers, the two terms μεταμέλεσθαι, μεταμέλεια, and μετανοεῖν, μετάνοια, although no doubt affected in their coloring by their differing etymological suggestions, and although μετανοεῖν, μετάνοια seems always to have been the nobler term, were practically synonymous. Both were used of the dissatisfaction which is felt in reviewing an unworthy deed; both of the amendment which may grow out of this dissatisfaction. Something of this undiscriminating usage extends into the New Testament. In the only three instances in which μεταμέλεσθαι occurs in the Gospels (Mt. 21:29, 32, 27:3, cf. Heb. 7:21 from Old Testament), it is used of a repentance which issued in the amended act; while in Lk. 17:3, 4 (but there only) μετανοεῖν may very well be understood of a repentance which expended itself in regret. Elsewhere in the New Testament μεταμέλεσθαι is used in a single instance only (except Heb. 7:21 from Old Testament) and then it is brought into contrast with μετάνοια as the emotion of regret is contrasted with a revolution of mind (2 Cor. 7:8 sq.). The Apostle had grieved the Corinthians with a letter and had regretted it (μετεμελόμην); he had, however, ceased to regret it (μεταμέλομαι), because he had come to perceive that their grief had led the Corinthians to repent of their sin (μετάνοια), and certainly the salvation to which such a repentance tends is not to be regretted (ἀμεταμέλητον). Here μεταμέλεσθαι is the painful review of the past; but so little is μετάνοια this, that it is presented as a result of sorrow,—a total revolution of mind traced by the Apostle through the several stages of its formation in a delicate analysis remarkable for its insight into the working of a human soul under the influence of a strong revulsion (verse 11). Its roots were planted in godly sorrow, its issue was amendment of life, its essence consisted in a radical change of mind and heart towards sin. In this particular instance it was a particular sin which was in view; and in heathen writers the word is commonly employed of a specific repentance of a specific fault. In the New Testament this, however, is the rarer usage. Here it prevailingly stands for that fundamental change of mind by which the back is turned not upon one sin or some sins, but upon all sin, and the face definitely turned to God and to His service,—of which therefore a transformed life (ἐπιστροφή) is the outworking. It is not itself this transformed life, into which it issues, any more than it is the painful regret out of which it issues. No doubt, it may spread its skirts so widely as to include on this side the sorrow for sin and on that the amendment of life; but what it precisely is, and what in all cases it emphasises, is the inner change of mind which regret induces and which itself induces a reformed life. Godly sorrow works repentance (2 Cor. 7:10): when we "turn" to God we are doing works worthy of repentance (Acts 3:19, 26:20, cf. Lk. 3:8).

It is in this, its deepest and broadest sense, that μετάνοια corresponds from the human side to what from the divine point of sight is called ἀνακαίνωσις, or, rather, to be more precise, that μετάνοια is the psychological manifestation of ἀνακαίνωσις. This "renewal" (ἀνακαινοῦσθαι, ἀνακαίνωσις, ἀνανεοῦσθαι) is the broad term of its own group. It may be, to be sure, that παλινγενεσία should take its place by its side in this respect. In one of the only two passages in which it occurs in the New Testament (Mt. 19:28) it refers to the repristination not of the individual, but of the universe, which is to take place at "the end": and this usage tends to stamp upon the word the broad sense of a complete and thoroughgoing restoration. If in Tit. 3:5 it is applied to the individual in such a broad sense, it would be closely coextensive in meaning with the ἀνακαίνωσις by the side of which it stands in that passage, and would differ from it only as a highly figurative differs from a more literal expression of the same idea. Our salvation, the Apostle would in that case say, is not an attainment of our own, but is wrought by God in His great mercy, by means of a regenerating washing, to wit, a renewal by the Holy Spirit.

The difficulty we experience in confidently determining the scope of παλινγενεσία, arising from lack of a sufficiently copious usage to form the basis of our induction, attends us also with the other terms of its class. Nevertheless it seems tolerably clear that over against the broader "renewal' ' expressed by ἀνακαινοῦσθαι and its cognates and perhaps also by παλινγενεσία, ἀναγεννᾶν (1 Pet. 1:23) and with it, its synonym ἀποκυεῖσθαι (James 1:18) are of narrower connotation. We have, says Peter, in God's great mercy been rebegotten, not of corruptible seed, but of incorruptible, by means of the Word of the living and abiding God. It is in accordance with His own determination, says James, that we have been brought forth by the Father of Lights, from whom every good gift and every perfect boon comes, by means of the Word of truth. We have here an effect, the efficient agent in working which is God in His unbounded mercy, while the instrument by means of which it is wrought is "the word of good-tidings which has been preached" to us, that is to say, briefly, the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The issue is, equally briefly, just salvation. This salvation is characteristically described by Peter as awaiting its consummation in the future, while yet it is entered upon here and now not only (verse 4 sq.) as a "living hope" which shall not be put to shame (because it is reserved in heaven for us, and we meanwhile are guarded through faith for it by the power of God), but also in an accordant life of purity as children of obedience who would fain be like their Father and as He is holy be also ourselves holy in all manner of living. James intimates that those who have been thus brought forth by the will of God may justly be called "first fruits of His creatures," where the reference assuredly is not to the first but to the second creation, that is to say, they who have already been brought forth by the word of truth are themselves the product of God's creative energy and are the promise of the completed new creation when all that is shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the liberty of the glory of the children of God (Rom. 8:19 sq., Mt. 19:28).

The new birth thus brought before us is related to the broader idea of "renewal" (ἀνακαίνωσις) as the initial stage to the whole process. The conception is not far from that embodied by our old Divines in the term "effectual calling" which they explained to be "by the Word and Spirit"; it is nowadays perhaps more commonly but certainly both less Scripturally and less descriptively spoken of as "conversion." It finds its further explanation in the Scriptures accordingly not under the terms ἐπιστρέφειν, ἐπιστροφή, which describe to us that in which it issues, but under the terms καλέω, κλῆσις which describe to us precisely what it is. By these terms, which are practically confined to Paul and Peter, the follower of Christ is said to owe his introduction into the new life to a "call" from God—a call distinguished from the call of mere invitation (Mt. 22:14), as "the call according to purpose" (Rom. 8:28), a call which cannot fail of its appropriate effect, because there works in it the very power of God. The notion of the new birth is confined even more closely still to its initial step in our Lord's discourse to Nicodemus, recorded in the opening verses of the third chapter of John's Gospel. Here the whole emphasis is thrown upon the necessity of the new birth and its provision by the Holy Spirit. No one can see the Kingdom of God unless he be born again; and this new birth is wrought by the Spirit. Its advent into the soul is unobserved; its process is inscrutable; its reality is altogether an inference from its effects. There is no question here of means. That the ἐξ ὕδατος of verse 5 is to be taken as presenting the external act of baptism as the proper means by which the effect is brought about, is, as we have already pointed out, very unlikely. The axiom announced in verse 6 that all that is born of flesh is flesh and only what is born of the Spirit is spirit seems directly to negative such an interpretation by telling us flatly that we cannot obtain a spiritual effect from a physical action. The explanation of verse 8 that like the wind, the Spirit visits whom He will and we can only observe the effect and say Lo, it is here! seems inconsistent with supposing that it always attends the act of baptism and therefore can always be controlled by the human will. The new birth appears to be brought before us in this discussion in the purity of its conception; and we are made to perceive that at the root of the whole process of "renewal" there lies an immediate act of God the Holy Spirit upon the soul by virtue of which it is that the renewed man bears the great name of Son of God. Begotten not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, nor of the will of man, but of God (Jno. 1:13), his new life will necessarily bear the lineaments of his new parentage (1 Jno. 3:9, 10; 5:4, 18): kept by Him who was in an even higher sense still begotten of God, he overcomes the world by faith, defies the evil one (who cannot touch him), and manifests in his righteousness and love the heritage which is his (1 Jno. 2:29, 4:7, 5:1). Undoubtedly the Spirit is active throughout the whole process of "renewal"; but it is doubtless the peculiarly immediate and radical nature of his operation at this initial point which gives to the product of His renewing activities its best right to be called a new creation (2 Cor. 5:17, Gal. 6:15), a quickening (Jno. 5:21, Eph. 2:5), a making alive from the dead (Gal. 3:21).

We perceive, then, that the Scriptural phraseology lays before us, as its account of the great change which the man experiences who is translated from what the Scriptures call darkness to what they call God's marvellous light (Eph. 5:8, Col. 1:13, 1 Pet. 2:9, 1 Jno. 2:8) a process; and a process which has two sides. It is on the one side a change of the mind and heart, issuing in a new life. It is on the other side a renewing from on high issuing in a new creation. But the initiative is taken by God: man is renewed unto repentance: he does not repent that he may be renewed (cf. Heb. 6:6). He can work out his salvation with fear and trembling only because God works in him both the willing and the doing. At the basis of all there lies an enabling act from God, by virtue of which alone the spiritual activities of man are liberated for their work (Rom. 6:22, 8:2). From that moment of the first divine contact the work of the Spirit never ceases: while man is changing his mind and reforming his life, it is ever God who is renewing him in true righteousness. Considered from man's side the new dispositions of mind and heart manifest themselves in a new course of life. Considered from God's side the renewal of the Holy Spirit results in the production of a new creature, God's workmanship, with new activities newly directed. We obtain thus a regular series. At the root of all lies an act seen by God alone, and mediated by nothing, a direct creative act of the Spirit, the new birth. This new birth pushes itself into man's own consciousness through the call of the Word, responded to under the persuasive movements of the Spirit; his conscious possession of it is thus mediated by the Word. It becomes visible to his fellow-men only in a turning to God in external obedience, under the constant leading of the indwelling Spirit (Rom. 8:14). A man must be born again by the Spirit to become God's son. He must be born again by the Spirit and Word to become consciously God's son. He must manifest his new spiritual life in Spirit-led activities accordant with the new heart which he has received and which is ever renewed afresh by the Spirit, to be recognized by his fellow-men as God's son. It is the entirety of this process, viewed as the work of God on the soul, which the Scriptures designate "renewal."

It must not be supposed that it is only in these semi-technical terms, however, that the process of "renewal" is spoken of in the Epistles of the New Testament any more than in the Gospels. There is, on the contrary, the richest and most varied employment of language, literal and figurative, to describe it in its source, or its nature, or its effects. It is sometimes suggested, for example, under the image of a change of vesture (Eph. 4:24, Col. 3:9, 10, cf. Gal 3:27, Rom. 13:14): the old man is laid aside like soiled clothing, and the new man put on like clean raiment. Sometimes it is represented, in accordance with its nature, less figuratively, as a metamorphosis (Rom. 12:2): by the renewing of our minds we become transformed beings, able to free ourselves from the fashion of this world and prove what is the will of God, good and acceptable and perfect. Sometimes it is more searchingly set forth as to its nature as a reanimation (Jno. 5:21, Eph. 2:4–6, Col. 2:12, 13, Rom. 6:3, 4): we are dead through our trespasses and the uncircumcision of our flesh; God raises us from this death and makes us sit in the heavenly places with Christ. Sometimes with less of figure and with more distinct reference to the method of the divine working, it is spoken of as a recreation (Eph. 2:10, 4:24, Col. 3:10), and its product, therefore, as a new creature (2 Cor. 5:17, Gal. 6:15): we emerge from it as the workmanship of God, created in Christ Jesus unto good works. Sometimes with more particular reference to the nature and effects of the transaction, it is defined rather as a sanctification, a making holy (ἁγιάζω, 1 Thess. 5:23, Rom. 15:16, Rev. 22:11; ἁγνίζω, 1 Pet. 1:22; ἁγιασμός, 1 Thess. 4:3, 7, Rom. 6:19, 22, Heb. 12:14, 2 Thess. 2:13, 1 Pet. 1:2; cf. Ellicott, on I Thess. 4:3, 3:13): and those who are the subjects of the change are, therefore, called "saints" (ἅγιοι, e.g., Rom. 8:27, 1 Cor. 6:1, 2, Col. 1:12). Sometimes again, with more distinct reference to its sources, it is spoken of as the "living" (Gal. 2:20, Rom. 6:9, 10, Eph. 3:17) or "forming" (Gal. 4:19, cf. Eph. 3:17, 1 Cor. 2:16, 2 Cor. 3:8) of Christ in us, or more significantly (Rom. 8:9, 10, Gal. 4:6) as the indwelling of Christ or the Spirit in us, or with greater precision as the leading of the Spirit (Rom. 8:14, Gal. 5:18): and its subjects are accordingly signalized as Spiritual men, that is, Spirit-determined, Spirit-led men (πνευματικοί, 1 Cor. 2:15, 3:1, Gal. 6:1, cf. 1 Pet. 2:5), as distinguished from carnal men, that is, men under the dominance of their own weak, vicious selves (ψυχικοί, 1 Cor. 2:14, Jude 19, σαρκικοί, 1 Cor. 3:3). None of these modes of representation more clearly define the action than the last mentioned. For the essence of the New Testament representation certainly is that the renewal which is wrought upon him who is by faith in Christ, is the work of the Spirit of Christ, who dwells within His children as a power not themselves making for righteousness, and gradually but surely transforms after the image of God, not the stream of their activities merely, but themselves in the very centre of their being.

The process by which this great metamorphosis is accomplished is laid bare to our observation with wonderful clearness in Paul's poignant description of it, in the seventh chapter of Romans. We are there permitted to look in upon a heart into which the Spirit of God has intruded with His transforming power. Whatever peace it may have enjoyed is broken up. All its ingrained tendencies to evil are up in arms against the intruded power for good. The force of evil habit is so great that the Apostle, in its revelation to him, is almost tempted to despair. "O wretched man that I am," he cries, "who shall deliver me out of the body of this death?" Certainly not himself. None knows better than he that with man this is impossible. But he bethinks himself that the Spirit of the most high God is more powerful than even ingrained sin; and with a great revulsion of heart he turns at once to cry his thanks to God through Jesus Christ our Lord. This conflict he sees within him, he sees now to bear in it the promise and potency of victory; because it is the result of the Spirit's working within him, and where the Spirit works, there is emancipation from the law of sin and death. The process may be hard—a labor, a struggle, a fight; but the end is assured. No matter how far from perfect we yet may be, we are not in the flesh but in the Spirit if the Spirit of God dwells in us; and we may take heart of faith from that circumstance to mortify the deeds of the body and to enter upon our heritage as children of God. Here in brief compass is the Apostle's whole doctrine of renewal. Without holiness we certainly shall not see the Lord: but he in whom the Holy Spirit dwells, is already potentially holy; and though we see not yet what we shall be, we know that the work that is begun within us shall be completed to the end. The very presence of strife within us is the sign of life and the promise of victory.

The church has retained, on the whole, with very considerable constancy the essential elements of this Biblical doctrine of "renewal." In the main stream of Christian thought, at all events, there has been little tendency to neglect, much less to deny it, at least theoretically. In all accredited types of Christian teaching it is largely insisted upon that salvation consists in its substance of a radical subjective change wrought by the Holy Spirit, by virtue of which the native tendencies to evil are progressively eradicated and holy dispositions are implanted, nourished and perfected.

The most direct contradiction which this teaching has received in the history of Christian thought was that given it by Pelagius at the opening of the fifth century. Under the stress of a one-sided doctrine of human freedom, in pursuance of which he passionately asserted the inalienable ability of the will to do all righteousness, Pelagius was led to deny the need and therefore the reality of subjective operations of God on the soul ("grace" in the inner sense) to secure its perfection; and this carried with it as its necessary presupposition the denial also of all subjective injury wrought on man by sin. The vigorous reassertion of the necessity of subjective grace by Augustine put pure Pelagianism once for all outside the pale of recognized Christian teaching; although in more or less modified or attentuated forms, it has remained as a widely spread tendency in the churches, conditioning the purity of the supernaturalism of salvation which is confessed.

The strong emphasis laid by the Reformers upon the objective side of salvation, in the enthusiasm of their rediscovery of the fundamental doctrine of justification, left its subjective side, which was not in dispute between them and their nearest opponents, in danger of falling temporarily somewhat out of sight. From the comparative infrequency with which it was in the first stress of conflict insisted on, occasion, if not given, was at least taken, to represent that it was neglected if not denied. Already in the first generation of the Reformation movement, men of mystical tendencies like Osiander arraigned the Protestant teaching as providing only for a purely external salvation. The reproach was eminently unjust, and although it continues to be repeated up to to-day, it remains eminently unjust. Only among a few Moravian enthusiasts, and still fewer Antinomians, and, in recent times, in the case of certain of the Neo-Kohlbrüggian party, can a genuine tendency to neglect the subjective side of salvation be detected. With all the emphasis which Protestant theology lays on justification by faith as the root of salvation, it has never failed to lay equal emphasis on sanctification by the Spirit as its substance. Least of all can the Reformed theology with its distinctive insistence upon "irresistible grace"—which is the very heart of the doctrine of "renewal"—be justly charged with failure to accord its rights to the great truth of supernatural sanctification. The debate at this point does not turn on the reality or necessity of sanctification, but on the relation of sanctification to justification. In clear accord with the teaching of Scripture, Protestant theology insists that justification underlies sanctification, and not vice versa. But it has never imagined that the sinner could get along with justification alone. It has rather ever insisted that sanctification is so involved in justification that the justification cannot be real unless it be followed by santification. There has never been a time when it could not recognize the truth in and (when taken out of its somewhat compromising context) make heartily its own such an admirable statement of the state of the case as the following:—"However far off it may be from us or we from it, we cannot and ought not to think of our salvation as anything less than our own perfected and completed sinlessness and holiness. We may be, to the depths of our souls, grateful and happy to be sinners pardoned and forgiven by divine grace. But surely God would not have us satisfied with that as the end and substance of the salvation He gives us in His Son. Jesus Christ is the power of God in us unto salvation. It does not require an exercise of divine power to extend pardon; it does require it to endow and enable us with all the qualities, energies, and activities that make for, and that make holiness and life. See how St. Paul speaks of it when he prays, That we may know the exceeding greatness of God's power to usward who believe, according to that working of the strength of His might which he wrought in Christ when He raised Him from the dead."

LITERATURE:—The literature of the subject is copious but also rather fragmentary. The best aid is afforded by the discussions of the terms employed in the Lexicons and of the passages which fall in review in the Commentaries: after that the appropriate sections in the larger treatises in Biblical Theology, and in the fuller Dogmatic treatises are most valuable. The articles of J. V. Bartlet in Hastings' B. D. on "Regeneration" and "Sanctification" should be consulted,—they also offer a suggestion of literature; as do also the articles, "Bekehrung," "Gnade," "Wiedergeburt" in the several editions of Herzog. There are three of the prize publications of the Hague Society which have a general bearing on the subject: G. W. Semler's and S. K. Theoden van Velzen's "Over de voortdurende Werking des H. G.," (1842) and E. I. Issel's "Der Begriff der Heiligkeit im N. T.," (1887). Augustine's Anti-Pelagian treatises are fundamental for the dogmatic treatment of the subject; and the Puritan literature is rich in searching discussions,—the most outstanding of which are possibly: Owen, "Discourse concerning the Holy Spirit" ("Works": Edinburgh, 1852, v. iii.); T. Goodwin, "The Work of the Holy Ghost in our Salvation" ("Works": Edinburgh, 1863, v. vi.); Charnock, "The Doctrine of Regeneration," Phil. 1840; Marshall, "The Gospel Mystery of Sanctification," London [1692], Edinburgh, 1815; Edwards, "The Religious Affections." Cf. also Köberle, "Sünde und Gnade im relig. Leben des Volkes Israel bis auf Christum," 1905; Vömel, "Der Begriff der Gnade im N. T.," 1903; J. Kuhn: "Die christl. Lehre der göttlichen Gnade" (Part I) 1868; A. Dieckmann, "Die christl. Lehre von der Gnade," 1901; Storr, "De Spiritus Sancti in mentibus nostris efficientia," 1779; J. P. Stricker, "Diss. Theol. de Mutatione homini secundum Jesu et App. doct. subeunda," 1845.—P. Gennrich, "Die Lehre von der Wiedergeburt: die christl. Zentrallehre in dogmengeschichtlicher und religions-geschichtlicher Beleuchtung," 1907; and "Wiedergeburt und Heiligung mit Bezug auf die gegenwärtigen Strömungen des religiösen Lebens," 1908; H. Bavinck, "Roeping en Wedergeboorte," 1903; J. T. Marshall, art. "Regeneration" in Hastings' ERE v. x.

-----

From Biblical Doctrines by B. B. Warfield